Perhaps the most embarrassing consequence of reading Victorian Sappho – Yopie Prins’s impressive account of how Victorian poets over the course of a century imagined, exploited and distorted the mysterious figure of Sappho – is being forced to confront one’s own mental images of the long-dead Greek poet. My own most cherished notions of her, I find, are at once detailed, puerile and unbending – a strange hodge-podge of Baudelaire, Mary Barnard and Ronald Firbank, all coloured still by the prejudicial fancies of a flannel-shirted, late Seventies lesbian adolescence:

SAPPHO: short, dark in appearance, teensiest hint of a moustache – a cross between Mme Moller (high school French teacher) and a slightly defective but still gorgeous Audrey Hepburn. More femme than butch in style (favours flowing chitons, the odd bangle, funny sandals with lots of straps) but good too at outdoorsy things, such as pounding in tent pegs and spotting constellations. Sings and dances, always ready with a hymn to Aphrodite, but gets mopey at weddings (always the bridesmaid, never the groom!). Dynamite in bed, of course, and totally gay: that stuff about being in love with Phaon and jumping off a cliff just not true! Ovid all bollocks. Would have been in love with me, had I lived in ancient Greece. May in fact have been referring to me in Wretched Tatty Papyrus Fragment No. 211 (Lobel-Page):

Come [Terry?] …

cast off your [air-cushioned?] Nikes

the [?] nightingale [?] …

Sappho of Lesbos has always seemed more phantasm than historical personage, of course: we know so little of her life and have so precious little of her poetry that editors and biographers over the centuries have more or less had to invent her. At least since the Renaissance, when the first fragmentary pieces of her writings began to circulate again in Europe after nearly two thousand years of neglect, she has been an object of unrelenting speculation, scandal and interpretative projection. As Yopie Prins puts it in her austerely post-structuralist idiom, to the extent that Sappho ‘survives’, she does so primarily as a ‘trope’ or rhetorical vessel, a linguistic figment or ‘ungrounded proper name’ endlessly available for imaginative occupancy by others. Hence Audrey Hepburn and the chitons.

What is known of her? Lauded throughout classical antiquity as the ‘Tenth Muse’ and greatest poet next to Homer, Sappho is believed to have lived on the Greek island of Lesbos some time around 600 BC. Plato and Aristophanes mention her; in ancient Rome, Horace and Catullus wrote famous imitations of her verses. Some six hundred years after her death, her renown was such that there was an attempt at a collected edition of her songs: a group of Greek scholars at Alexandria are said to have gathered together all of her known lyrics, organised them according to metrical scheme into nine books, and transcribed them onto papyrus scrolls.

Most records of Sappho disappeared, however, after the fall of Rome. During the Middle Ages both she and her work were largely forgotten. (According to one legend, the Christian patriarch Gregory of Nazianzos, offended by the licentiousness of her subject-matter, put her books to the torch in 380 AD.) Neither Dante nor Chaucer refers to her. Only with the recovery and translation of certain ancient texts in the Renaissance – Longinus’ On the Sublime, for example, in which the famous and much-admired Fragment 31 (‘He seems to me equal to the gods’) appears as a quotation – were bits and pieces of her poetic corpus gradually reassembled. The salvage operation has continued ever since, with several Sapphic fragments reappearing only in this century. The sum total of surviving texts, however, remains pitifully small: just one complete poem (the so-called ‘Hymn to Aphrodite’) and about two hundred tiny scraps of verse, many of them – agonisingly – only a word or two long. Sappho still seems more ‘lost’ than found, and barring any extraordinary archaeological discoveries, appears likely to remain so permanently.

The notorious controversy (now many centuries old) over Sappho’s sex life is related to these gaps in the historical and textual record. Ancient writers often spoke of her as a homosexual libertine: the early Christian writer Tatian described her as a ‘love-crazed female fornicator who even sings about her own licentiousness’. And indeed as more poem-fragments surfaced after the Renaissance – many addressed to beautiful girls and suffused with cryptic erotic fervour – she came to be regarded in sophisticated quarters as indisputably a lover of women. By the 17th and 18th centuries, she was a stock character in Latin, French and English pornography, and the term ‘Sapphist’ (later followed by ‘Lesbian’) began to circulate as a popular synonym for ‘tribade’.

Seemingly at odds with the homosexual identification, however, was the curious legend of Sappho’s disastrous passion for Phaon, a handsome young ferryman whose rejection of her is said to have prompted her suicide. (In the classic account, beset by love-anguish, she is supposed to have leapt from the Leucadian cliffs into the roiling sea below.) Ovid dramatised the suicide story in the Heroides (a bestseller of the 16th and 17th centuries) and ever after poets, scholars and ordinary readers struggled to reconcile Sappho-the-apparent-lesbian with Sappho-the-despondent-lover-of-Phaon. Early English imaginative writers seemed able to absorb the disparity relatively calmly: both Donne, in his ‘Sapho to Philaenis’ (1633), and Pope, in ‘Sappho to Phaon’ (1712), for example, presented Sappho as bisexual. But later, more prudish commentators were disturbed by the whole messy situation. Uncomfortable in particular with the long-standing rumours of Sappho’s homosexual ‘impurity’ – as indeed with homoerotic readings of her verse in general – 18th and 19th-century editors and translators fixed on the Phaon legend as a convenient way of debunking the Sappho-as-lesbian tradition. To focus on her fatal leap was one way of asserting the poet’s erotic ‘normalcy’ even in the face of scattered, often obscure, yet mounting textual evidence to the contrary.

Modern classicists have yet to resolve the biographical enigmas, though most, it must be said, now recognise a homoerotic content in the Sapphic corpus and view the Phaon story as apocryphal (and alien) accretion. Some have argued there may have been two ‘Sapphos’ in antiquity – one a poet and one a courtesan – and that their legends became somehow mixed up. Others suggest that the Phaon-suicide story may hint at some archaic sacrificial ritual – even that Sappho may have been pushed off a cliff, perhaps as punishment for nameless (homosexual?) debaucheries. Still others, such as Jane McIntosh Snyder, suggest that the Phaon myth may have arisen from an ancient exegetical slip; for

given the obvious mythological and metaphoric implications of the story, it is likely that if Sappho ever did refer in her songs to leaping off the White Rocks of Leukas, she meant the phrase in a non-literal way, perhaps as a metaphor for falling into a swoon. Eventually, it may be that later writers interpreted the phrase (if indeed she used it) as referring to a literal leap, thus giving rise to the suicide legend.

The controversy is worth mentioning because it turns out to be so central to Prins’s new book – might indeed be said to haunt it at a fairly deep level. Victorian Sappho deals with that period in Sappho’s modern reception history – the 19th century – when the interpretative battle over the poet’s libidinal orientation was at its height. From one angle Prins’s book seems a mostly straightforward, if somewhat cool, exercise in historical demystification. Her overriding goal, Prins asserts in the introduction, is not to adjudicate between conflicting Sapphic myths, but to show how by the end of the century ‘Sappho had become a highly overdetermined and contradictory trope within 19th-century discourses of gender, sexuality, poetics and politics.’ Drawing an analogy from case grammar, she describes her aim as one of exposing how different Victorian writers ‘declined’ the ‘name’ of Sappho – i.e. by fabricating fanciful identities for her:

Each chapter of Victorian Sappho proposes a variation on the name, demonstrating how it is variously declined: the declension of a noun and its deviation from origins, the improper bending of a proper name, a line of descent that is also a falling into decadence, the perpetual return of a name that is also a turning away from nomination.

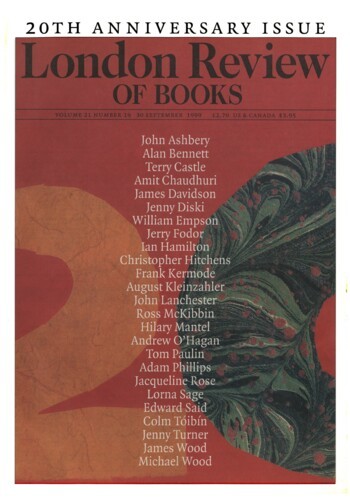

Yet even as she claims not to be taking any point of view on Sappho’s mixed-up legend – merely exposing a ‘declension’ or ‘decadence’ – she manages to do a little improper bending of her own, and, hugger-mugger, ends up throwing in her lot with Sappho the Phaon-obsessed: the one who leaps from the cliff. (The cover of Victorian Sappho not so secretly suggests as much: it reproduces Charles-Auguste Mengin’s ghastly-glorious 1877 painting of the poet, bare-breasted beneath a swirling black sky, gazing mournfully down at the Aegean.) Watching Prins make this particular plunge, Post-Modern tresses lifting in the wind, is to be struck again by how difficult it is, in life or literary criticism, to avoid the classic Sapphic double-bind: take the girls or take the jump.

None of which is to say this isn’t an arresting book: the most penetrating on the poet since Anne Carson’s Eros the Bittersweet (1987) and Joan DeJean’s Fictions of Sappho (1989). Prins’s immersion in the Victorian art and literature of Sappho is deep; the sophistication of her approach formidable. And as her opening remarks suggest, the topic of Sappho’s 19th-century reception is multifaceted enough to allow for intense meditation on a host of crucial literary-historical issues: the evolution and ideology of women’s writing, the problem of translation, the uses of Hellenism, the history of English metrics, the nature of lyric. By any measure this book (Prins’s first) is a debut of major ambition and considerable achievement.

Still, Prins’s concerns are rhetorical – even deconstructionist – rather than psycho-biographical, and she pursues them in a manner that the Sapphically-inclined Sapphist will no doubt find off-putting. The study is divided into four parts, each representing a distinct aspect of the poet’s 19th-century legacy. In the first section, ‘Sappho’s Broken Tongue’, Prins provides a useful potted chronology of English translations of Sappho, up to and including Dr Henry Wharton’s highly influential Sappho: Memoir, Text, Selected Renderings and a Literal Translation (1885). The much-translated (and notoriously strange) Fragment 31 – quoted below in Anne Carson’s closely literal modern version – comes in for particular attention:

He seems to me equal to the gods that man

whoever he is who opposite you

sits and listens close

to your sweet speakingand lovely laughing – oh it

puts the heart in my chest on wings

for when I look at you, a moment, then no speakingis left in me

no: tongue breaks, and thin

fire is racing under skinand in eyes no sight and drumming

fills ears

and cold sweat holds me and shaking

grips me all, greener than grass

I am and dead – or almost

I seem to me.

Confronted by this arousing yet mutilated utterance – almost certainly only the beginning of a much longer poem – English readers such as Wharton, Prins writes, found in the very ambiguity and truncation of its lines an ‘ideal medium’ for ‘sublime transport’.

Yet already Prins shows her hand. What interests her most about Fragment 31 is not the apparently homoerotic situation – the poet seems to address a young woman with whom she is infatuated – or the way that English translators, well into the 19th century, chose either to emphasise or obfuscate that fact. (One masterpiece of dishonest revisionism, John Hall’s translation of 1652, begins

He that sits next to thee now and hears

Thy charming voyce, to me appears

Beauteous as any DeityThat rules the skie.

How did his pleasing glances dart

Sweet languors to my ravish’d heart

At the first sight though so prevailed

That my voyce fail’d.

– precisely so as to disguise the female object of the speaker’s yearning.) What preoccupies her instead is what she sees as the fragment’s allegorical significance: the way it dramatises through the metaphor of the ‘broken tongue’ a powerful yet paradoxical conception of lyric poetry itself.

The argument here is not for the faint of heart. Critics since Longinus, Prins observes, have often fixed on a psychokinetic paradox at the heart of the fragment: the poet ‘is simultaneously losing composure and composing herself, falling apart in the poem and coming together as a poem that seems to speak, with heightened eloquence, to the reader’. For Prins, the ‘self-defacing’ logic of Fragment 31 – the poet’s tongue is ‘broken’, yet through the art of the translator, who reconstitutes and reorganises her scattered parts, we seem nonetheless to hear her ‘voice’ – haunts Sappho’s literary afterlife as well as the Western lyric tradition she is said to initiate:

What makes Sappho sublime is the mutilation of the Sapphic fragments, allowing her to be simultaneously dismembered and remembered, in a complex mediation between corpse and corpus: the body of the poet is sacrificed to the body of her song, and this body of song is sacrificed to posterity, which recollects the scattered fragments in order to recall Sappho herself as the long-lost origin of lyric poetry.

Sappho, for Prins, is in the end a mere ‘name’: the proper name of someone who says, oddly enough, that she cannot speak. With each new appropriation of the Sapphic name, she is written back into being, but falsely. She remains the quintessential lyric poet precisely because whatever ‘subjectivity’ she models is merely the accumulated effect of countless lyric misreadings and mistranslations.

I think I understand this: if I’ve got it right, it’s rather like listening to a recording of Patsy Cline singing ‘I Fall to Pieces’. Even though Cline died in a plane crash nearly forty years ago, to hear her sing about falling to pieces (‘each time I see you walk by’) is to experience the fantastical illusion that she is present. The fact that she is dead and literally in pieces (one presumes) is a paradoxical boon, for we are thus free to see her – as Prins suggests various Victorian poets did with Sappho – ‘as an imaginary totalisation, imagined in the present and projected into the past’. Each time we turn on the CD player, ‘Patsy’ opens herself up to our fantasy – thanks to the revivifying fakery of electronically reconstituted sound.

Whatever one makes of the Derridean turns in Prins’s argument, the moody pre-occupation with Sapphic absence – with the notion that no one who claims to speak ‘in the name of Sappho’ ever really does – undoubtedly shapes the rest of Victorian Sappho. In remaining sections Prins looks closely at three of the more spectacular instances of 19th-century Sapphic impersonation. First is the strange case of ‘Michael Field’: a pair of homosexual female lovers, aunt and niece, whose jointly-authored, Sapphically-inspired verses in Long Ago (1889) set the stage for later lesbian appropriations of the poet. Second up is Swinburne, whose outrageously sado-masochistic imitations of a Sapphic ‘voice’ in ‘Anactoria’ and other poems of the 1860s and 1870s led to his work being dubbed ‘the reductio ad horribilem of … intellectual sensualism’. And last but not least Prins examines a number of now mostly forgotten ‘English Sapphos’: early 19th-century female poets such as Letitia Elizabeth Landon and Caroline Norton, whose kitsch set-pieces on the theme of Sappho’s suicide (‘The Last Song of Sappho’, ‘The Picture of Sappho’ etc) at once confirmed Sappho’s heroic status as originary ‘Poetess’ and sent her – repeatedly – to a vertiginous yet mysteriously seductive death.

Prins’s post-structuralist allegiances, it must be said, make for some absorbing close readings. A crucial theme of the book is how, in order to create something ‘in the name’ of Sappho, a writer must also ‘forget’ something about her – almost wilfully blind himself to some critical aspect of her legacy. Out of this self-inflicted purblindness comes an intensification of vision – along whatever privileged line the poet-imitator has chosen to preserve. In the case of Katherine Bradley (1846-1914) and Edith Cooper (1862-1913), the two women who together made up the authorial phenomenon of ‘Michael Field’, the strategic forgetting, as it were, of the Ovidian Sappho – of the Sappho who dies out of love for Phaon – made it possible for them to exploit the Sapphic fragments collected in Wharton as ‘prompts’ for a delicately homoerotic, collaboratively-authored love verse:

Aὺταρ όραιαι στεφανηπλόκευν

They plaited garlands in their time;

They knew the joy of youth’s sweet prime,

Quick breath and rapture;

Theirs was the violet-weaving bliss,

And theirs the white, wreathed brow to kiss,

Kiss, and recapture.

Phaon, Prins notes, is mentioned in some of the first poems in Long Ago as a figure for ‘the ravages of heterosexual desire’, but banished from later poems, as Bradley and Cooper attempt to reclaim between them an all-female imaginary space, or textual ‘field’, in which love between women can flourish. In this curiously double, testosterone-free projection of Sapphic ‘voice’, Bradley and Cooper – who always maintained they were so ‘closely married’ that after bouts of composition they knew not who had written what lines – found the perfect metaphor for their own sensuous and creative ‘interlacing’. ‘Composing poems for Long Ago,’ Prins writes, ‘Bradley and Cooper enact the very premise of their collaboration, the mutual implication of each in the writing of the other and the eroticising of that textual entanglement by turning it into an infinitely desirable feminine figure.’ Most of the poems, admittedly, are a bit drippy – an odd mixture of flowery neoclassical pastiche and 1890s-ish lezzie soft-core:

What praises would be best

Wherewith to crown my girls?

The rose when she unfurls

Her balmy, lighted buds is not so good,

So fresh as they

When on my breast

They lean, and say

All that they would,

Opening their glorious, candid maidenhood.

Still, one suspects the girl-shaken Sappho of Fragment 31 might have approved.

In the case of Swinburne (1837-1909) the process of strategic forgetting took a far kinkier turn. In ‘Anactoria’, a dramatic monologue from 1866 in which Sappho is overheard addressing her young lover Anactoria, Swinburne ignores both the Ovidian Sappho and the avatar of ‘Michael Field’-style homosexual tendresse in order to re-create his Sappho as a monstrous (even cannibalistic) sexual sadist:

Ah that my lips were tuneless lips, but pressed

To the bruised blossom of thy scourged white breast!

Ah that my mouth for Muses’ milk were fed

On the sweet blood thy sweet small wounds had bled!

That with my tongue I felt them, and could taste

The faint flakes from thy bosom to the waist!

That I could drink thy veins as wine, and eat

Thy breasts like honey! that from face to feet

Thy body were abolished and consumed

And in my flesh thy very flesh entombed!

Here Prins is brilliant, linking Swinburne’s Venus-in-Furs treatment of the poet both with his well-known flagellation mania – around the time he was writing ‘Anactoria’ he was also working on a volume of ‘bum-tickling’ pornographic eclogues known as The Flogging Block – and his obsession with poetic form. Swinburne inevitably associated the metrical rhythms of poetry, she suggests, with imaginary scenes of beating and punishment. His elaborate experiments with the so-called Sapphic stanza (three five-stress lines with a fourth half-line at the end of the stanza) were not simply attempts to find in the English accented line an equivalent for Sappho’s Greek, in which metre is determined by vowel length, but a way of commemorating fetishistically the primitive, smarting rhythm he mentally connected with lyric verse and his own art. Given such a fantasy scenario, the vulnerable, tongue-tied Sappho of Fragment 31 was of little use. He preferred to imagine her – his favourite poet – as an eager, schoolmistressy dominatrix, instilling the sacred rhythms of verse in her Swinburnean poet-pupils by way of the birch:

Would I not hurt thee perfectly? not touch

Thy pores of sense with torture, and make bright

Thine eyes with bloodlike tears and grievous light?

Strike pang from pang as note is struck from note,

Catch the sob’s middle music in thy throat,

Take thy limbs living, and new-mould with these

A lyre of many faultless agonies?

Ultimately, Prins suggests, in complex later poems such as ‘On the Cliffs’ (1880), examined here with intricate care, Sappho became an even more abstract presence in Swinburne’s poetic imagination: a kind of ‘rhythmicised body’ or corporeal pattern, ardently craved, which he sought to reinscribe, ever more perversely, in the exquisite perturbations of his own beat-driven verses.

The horde of female poets taken up in the final chapter, Mary Robinson (1758-1800), Felicia Hemans (1793-1835), Letitia Elizabeth Landon (1802-38), Caroline Norton (1808-77), Christina Rossetti (1830-94) and Mary Cowden Clarke (1809-98), are hardly as daring but equally morbid. Lesbianism (nice or nasty) be damned – they ‘remember’ Sappho solely as the maundering, soul-baffled lover of Phaon. This, for Prins, is the most retrograde, yet also most revealing ‘declension’ of Sappho’s name in the 19th century: her portrayal as love-struck heterosexual suicide in a gaggle of terminally dreary death-leap poems authored by women.

Though composed at the very end of the 18th century, Mary Robinson’s ‘Sappho to Phaon’ (1796) is typical, alas, of this otiosely feminine genre:

Oh! can’st thou bear to see this faded frame,

Deform’d and mangled by the rocky deep?

Wilt thou remember, and forbear to weep,

My fatal fondness, and my peerless fame?

Soon o’er this heart, now warm with passion’s flame,

The howling winds and foamy waves shall sweep;

Those eyes be ever clos’d in death’s cold sleep,

And all of Sappho perish but her name!

And Prins herself gets a bit morbid here, citing poem after poem to make the same point: that such self-abnegating verse expressed a deep-dyed anxiety about assuming visionary authority in a male-dominated poetic world. Sappho is the primordial woman writer – the greatest ‘Poetess’ ever – but the only way to imitate her, it seems, is by bungee-jumping without a cord. Even as female poets try to ‘ground’ their accession to poetry by impersonating Sappho it also ‘falls’ to them ‘to perform this foundational claim as itself an act of falling or continually losing ground’. The result is a killing paradox: ‘women poets rise to authorship’ only by falling into ‘the abyss of female authorship, where the Poetess proves to be the personification of an empty figure’. It is no surprise, given Prins’s slightly dizzying logic here, that with the exception of the grave and great Rossetti, most of these excruciating ‘English Sapphos’ have themselves been forgotten, together with their wretched poems.

Prins’s obsessiveness is compelling – even too compelling. For it is at this point that one begins to feel something is wrong with Victorian Sappho: indeed, has been wrong all along, despite how good it is. Some obvious line of thought is being resisted; things seem oddly back to front. It is not simply that Prins herself ‘forgets’ works – or historical contexts – that weaken her thesis. The argument that Victorian women writers imagined themselves as so many Sapphos-about-to-commit-suicide in order to symbolise a feminine sense of poetic disenfranchisement would seem to be compromised, at the least, by the existence of numerous male-authored 18th and 19th-century poems that appear to do something similar. What of Cowper’s ‘The Castaway’ (1799), in which the speaker is similarly poised on the edge of some self-imposed lyric dissolution? The famous tolling, final lines (‘We perished, each alone;/But I beneath a rougher sea,/And whelmed in deeper gulfs than he’) are as self-evacuating as anything in Robinson or Hemans. In Matthew Arnold’s droogy play-in-verse Empedocles on Etna (1852) the main speaker is the slave-philosopher, expostulating on his misery and about to plunge into the fiery volcano to his death (‘Take thy bough, set me free from my solitude;/I have been enough alone!’). Given what appears to be a fad in the period for such I’m-just-about-to-kill-myself poems, how specifically female is the sensation of disenfranchisement?

A deeper problem, however, lies in Prins’s attitude, which I use here in the slang American sense: she is like the brooding, jagged hostess in the hip urban restaurant who doesn’t want anyone to have any fun (let alone feel nourished) despite all the glamorous people and interesting food. A powerful oddity of Victorian Sappho is that it works backwards chronologically. Prins admits as much in her epilogue:

I might have started with the final chapter, tracing the emergence of Sappho as proper name for the Poetess within sentimental women’s verse of the early Victorian period, setting the stage for Algernon Swinburne’s sensational reappropriation of this lyric fig-ure for high Victorian poets, and continuing with the conversion of Sappho of Lesbos into a lesbian Sappho by Michael Field toward the end of the century.

She has refused the obvious chronological ordering, she says, in order to keep her readers from assuming any ‘progress’ or development in the evolution of Sapphic iconography. She is particularly concerned that we not latch onto the notion (which she then perversely elaborates) that ‘while earlier versions of Sappho are primarily mediated by Ovid’, later ones give way to ‘a Sapphic corpus reconstructed from Greek fragments’, which is in turn read by Michael Field, John Addington Symonds and countless others as explicitly lesbian.

Surely this is cutting off one’s nose to spite one’s corpus? The self-conscious manoeuvring here suggests how deeply Prins holds to a view of literary history at once fashionably Post-Modern and painfully anorexic: that literature is nothing more – can be nothing more – than a system of endless displacements, cheats and losses. The more we try to grasp someone named Sappho the more she eludes us. The one we had hoped to embrace falls away from us. Prins’s backwards ordering (which is at least as artificial an arrangement as any more straightforward chronology) seems designed to instil this sense of loss in the reader by way of an almost kinesthetic dysphoria – a continuous sense of everything ‘declining’, falling and getting worse. Thus we go from Michael Field (pretty poems about hugging and kissing) to Swinburne (weird poems about whipping and hurting) to the ‘English Sapphos’ (gormless poems about lying all dead and mangled in the seaweed). A feeling of overkill sinks in as Prins describes yet another Sapphic suicide poem, as if pleasure (charmingly homosexual) had to be transformed into fatality (agonisingly heterosexual) over and over again. Go straight and die, Sappho! It’s a desolating outlook; as if Prins were saying: look where our attempts to recognise the literary past take us – straight to the bottom of a cliff, again and again.

And is it true? At the risk of revealing one’s Audrey Hepburnism as incurable, one might wish to demur. We have got somewhere – and something – over the long process of Sapphic recovery and reception. We have more fragments than we used to; we understand them better. And surely it is not pure fancy to read into them a homosexual dimension? Given that all truths remain approximate truths, might one not argue, still, that Michael Field’s lesbian image of Sappho is closer to the view of her held by present-day classicists – indeed is more accurate – than that of the tedious ‘English Sapphos’? Might not the image of Sapphic girl-loving have something more to it than mere wishful projection? The story of how scholars as well as ordinary readers came to accept the Sapphic fragments as love poems addressed to women is one of the most fascinating and chequered stories in all of literary reception history. (And contrary to Prins’s assertion that the poet’s ‘association with lesbian identity is a particularly Victorian phenomenon’ the coding of Sappho as Sapphist has a complex 17th and 18th-century genealogy as well, as the work of Emma Donoghue and others has shown.) Yet none of this history carries any ultimate weight in Victorian Sappho. All representations of Sappho are equally false – mere figments or ‘translation effects’, written over poor old Sappho’s dead body.

Even if this were the case, so what? One might still argue for a more forgiving view of human image-making. Prins is as scathing as any Yale School deconstructionist of the late Seventies in her contempt for the rhetorical manoeuvre known as ‘prosopopoeia’ – more commonly known as ‘personification’: ‘the figure that gives face by conferring speech upon a voiceless entity, yet in so doing also defaces it.’ Yet what is life itself but an endless series of acts of personification? Every time we think about other people – attribute motives, assume traits, try to understand what they are saying or wanting to say – we engage in personification. It is easy enough to say the resulting image is false, but it is also all we have. There is no other point of access: no other ‘person’ (in literature or life) than the one we’re forced to come up with.

Given the fragmentary nature of the record, most of our presumptions about Sappho must inevitably be hesitant, hedged round, imperfect. The incompleteness of the poems themselves must likewise frustrate mightily, just as it frustrates us to hear about other wonderful lost things: Homer’s comic epic, the vast majority of Monteverdi’s operas, Old Master paintings destroyed in wars, the Mozart or Debussy (or Kurt Cobain) songs that never got written because the composer died young. But there is always room to rejoice in what does survive, however compromised or partial its form. Sappho, whoever she was, left an extraordinary amount of beauty in her wake, precisely in the shape of her imitations – the touching, provocative, endlessly gorgeous body of translation she inspired. One would never know it from reading the melancholy Prins, however, or indeed that some of Sappho’s fragments are as funny and joyful as they are lovely:

Now to delight my women friends

I’ll make a beautiful song of this affair.

*

certainly now they’ve had quite enough

of Gorgo

*

Though it isn’t easy for us to rival

goddesses in the loveliness of their figures

*

I think that someone will remember us in another time.

These are translations, of course – from Jim Powell’s Sappho: A Garland (1993). I’m sure some things have gone missing, but I don’t really care. She sounds like someone I would like.

Send Letters To:

The Editor

London Review of Books,

28 Little Russell Street

London, WC1A 2HN

letters@lrb.co.uk

Please include name, address, and a telephone number.