Like Diogenes in his tub, Roger Scruton has stripped himself of his professorship of aesthetics to rail, ungowned, against the age in which fate has deposited him. Scruton’s opposition to the times has two current manifestations: one is his lyrical advocacy of the feudal harmonies of the fox-hunt; the other is his hatred of ‘yoof’ culture. In An Intelligent Person’s Guide to Modern Culture* he defines culture three ways. ‘Common culture’ – what anthropologists study – is based in social life and examines how we use our knives and forks. What he calls ‘high culture’ is a quasi-religious superstructure conceived in the Renaissance, and refined in the Enlightenment and Romantic periods. Scruton has evidently been impressed by Matthew Arnold’s declaration that ‘the future of poetry is immense,’ and by Arnold’s confidence that high art can fill the vacancy left by the slow death of God: ‘there is,’ Scruton mystically claims, ‘a making whole, a rejoining of the self to its rightful congregation that come through art and literature.’ He believes that, like hunting, reading Jane Austen is a binding social ritual. TV adaptations don’t count.

‘The property of an educated élite’, high art was barely held onto by the Modernists, and has been lost entirely in the weltering wastes of Post-Modern kitsch, with its ‘institutionalised flippancy’. As high art filled the gap left by religion, so ‘popular art’ has swamped the one vacated by high art. Its profane media are technological, electronic and Americanised: MTV, CD-propagated pop music, Damien Hirst’s embalmed sheep, slasher movies and Pulp Fiction. Popular culture is a ‘globalised, commercialised mish-mash’ which ‘roars’ all around us. It is ‘pre-eminently a culture of youth’ – and an apocalyptic portent:

Among youth, as we know it from our modern cities, a new human type is emerging. It has its own language, its own customs, its own territory and its own self-contained economy. It also has its own culture – a culture which is largely indifferent to traditional boundaries, traditional loyalties and traditional forms of learning. Youth culture is a global force, propagated through media which acknowledge neither locality nor sovereignty in their easy-going capture of the airwaves: ‘one world one music’ – in the slogan adopted by MTV, a station [sic] which assembles the words, images and sounds which are the lingua franca of modern adolescents.

It is not Scruton’s habit to go into detail but he does catalogue some examples from the anthem-makers of this new human type:

there is a particular kind of pop music, typified by such cult groups as Nirvana, REM, the Prodigy and Oasis, which has a special claim on our attention, since it represents itself as the voice of youth, in opposition to the world of adults. In the music of such groups words and sounds lyricise the transgressive conduct of which fathers and mothers used to disapprove, in the days when disapproval was permitted.

According to Scruton, these musicians (so to dignify them) are artists (so to dignify them) of the ‘strangulated cry’: ‘trapped in a culture of near-total inarticulateness the singer can find no words to express what most deeply concerns him.’

Scruton’s knowledge of pop music falls well below the level of modest. He thinks, as is evident from a later parenthetic diatribe, that ‘REM’ is the name of the lead singer as well as the group. Let that pass. The notion that this particular group, at this moment, represents the voice of ‘youth’ is peculiar enough. REM’s lead singer and lyricist, Michael Stipe, is knocking on 40; other members of the group are older (one, the percussionist Bill Berry, has taken early retirement, on grounds of advanced age and poor health). Stipe is as close in age to Roger Scruton as to Liam Gallagher and, on photographic evidence, has aged less gracefully than his aesthetician critic. The back jacket of the Intelligent Person’s Guide displays a full-page photograph of the author, in his tanned, coiffed and open-necked glory. He could model for Michelangelo. Since REM’s 1995 Monster tour, Stipe, once as elfinly beautiful as the young Truman Capote, has affected a shaven-headed, emaciated look. Scurrilous columnists have suggested that Stipe’s shaven pate is a version of the Bruce Willis baldness cure. On his latest video he poses naked and writhing. The spectacle of this gaunt, hairy-bodied and bony-headed, middle-aged man narcissising in the nude is creepy.

One can read Stipe-the-starveling in different ways. He likes enigma. Is he bisexual? interviewers ask. No, he replies, he is ‘sexual’. A gifted mimic, physically and vocally, he can change himself with chameleon facility – ‘I can be whatever you want,’ he has told his fans. Familiar, like many of his generation, with the disciplines of the 12-step group, he likes to ‘identify’. His current appearance may be an act of identification with PWAs (his equivalent of the red ribbon), with Bosnian refugees, Sudanese famine victims or Jodie Kidd.

My reading of Stipe’s prematurely geriatric persona is less cynical. During its heyday in the Eighties, the group was – like most of the industry – heavily into drugs. They have fought their coke-wars, and are now survivors. In the late Nineties, Stipe and the other members of the band have adopted an ostentatiously straight life style. Peter Buck and Bill Berry (drummer, retd) are happily married; their families (wives, babies, baby-minders) accompany them on tour and stand in the wings while Daddy does his stuff. Stipe is unpartnered, but at American concerts his parents (to whom he is devoted) look proudly from their royal-box vantage-point at their fabulous son. Stipe is personally abstemious: his one visible vice nowadays is caffeine (he will, as his song says, ‘settle for a cup of coffee’). He donates generously and unobtrusively to good causes (Greenpeace, Tibet). The image which he now wishes to wrap around himself is that of a man who has worn down into a world-weary, stoical goodness. With Up (REM’s 11th album in 17 years) Stipe announced that what ‘I wanted was for there to be no hint of distancing myself through irony or cynicism. We’ve all been through that.’ He offers an exegesis of one of the tracks on the record, ‘The Apologist’:

I’ve had the title on the wall in my office for about four years. So I wanted to write that song. Essentially, it’s about a guy that’s been through some kind of a detox or 12-step programme and, as part of his therapy, is going back to apologise to all the people from his past life, or from his former life, for the person he was … I wrote this song … so there’s a kind of universality to it. Specific enough that it doesn’t seem like a bundle of clichés tied together. But unspecific enough that pretty much anyone could listen to the song and apply it to themselves and to their own life and take from it what they need to.

‘The Apologist’ is vitiated by Stipe’s fascination with stigmata and the relentlessly self-loving display of masochistic pain. But neither the song, nor his gloss on it, could be called a ‘strangulated cry’.

As what Scruton calls a ‘totem of youth’, Stipe is an unlikely candidate. The band’s popularity seems to have peaked: Up entered the American charts at No. 3 when it was released in October, but has since bombed. It has, however, done well with Europe’s supposedly more sophisticated audiences. Hence the normally reclusive Stipe’s flurry of UK promotional interviews over the last few weeks.

After their $80 million deal with Warner in 1996, REM are financially secure. Stipe wants to use the group’s freedom from the captious tyranny of the fan to ‘push away from the stuff we had done before’, and do something ‘really experimental … something very fucking real’. Paradoxically, this has meant something more limpid than REM’s earlier and notoriously impenetrable lyrics. There is a website devoted to decoding the baffling surrealities of numbers like ‘The Sidewinder Sleeps Tonite’, though it fails, by and large, to throw much light on the subject.

In his more recent albums, Stipe has given up automatic composition in which ‘the lyric just kind of tumbled out of me.’ He now applies the term ‘writer’ to himself and wants his lyrics to be understood. More particularly, he has discovered the dramatic monologue. Up features a number of tracks in which the poet-singer projects himself into people as unlike himself as, well, myself and Roger Scruton. Take these verses from ‘The Sad Professor’. You don’t need a website to make sense of them:

late afternoon, the house is hot.

I started, I jumped up.

everyone hates a bore.

everybody hates a drunk.this may be a lit invention

professors muddled in their intent

to try to rope in followers

to float their malcontent.

as for this reader,

I’m already spent.late afternoon, the house is hot.

I started, I jumped up.

everyone hates a sad professor.

I hate where I wound up.

(Stripped of musical accompaniment, the words are thin. A few bars of the recorded version can be heard at the Warner website).

I don’t know the identity of the ‘lit professor’ in Michael Stipe’s mind here. I would like to think it’s me. He met me shortly before writing the song. I’m a professor of literature. I used to be a drunk. My enemies doubtless think I’m a bore. My friends may think I’m sad. And, like most academics, I’m not entirely happy about where I wound up. But, of course, this is to fall into the error of all those little girls (and boys) who imagine that George Michael is singing to them, and them alone. What is remarkable is that far from ‘lyricising the transgressive conduct of youth’, Michael Stipe is serenading me and Roger Scruton.

The track that stands out on Up is ‘Daysleeper’. As a musician, Michael Stipe is himself a daysleeper, but the persona adopted here is that of an inventory-control clerk, in a multinational dispatch firm (United Parcels?). He sits in front of a glaring computer monitor and fantasises a lonely omnipotence over his firm’s global territory. Like the astronomer in Johnson’s Rasselas, who thinks that his observations make the stars keep their courses in the heavens, he is going stark-staring mad. I quote the opening verses:

receiving department, 3 a.m.

staff cuts have socked up the overage

directives are posted.

no callbacks, complaints.

everywhere is calm.Hong Kong is present

Taipei awakes

all talk of circadian rhythmI see today with newsprint fray

my night is coloured headache grey

daysleeperthe bull and the bear are marking

their territories

they’re leading the blind with

their international gloriesI’m the screen, the blinding light

I’m the screen, I work at night.

In its musical setting ‘Daysleeper’ is a striking song. Of course, it cannot transcend its genre – very good it may be, but it’s only a very good popular song. It dramatises the stock-market-driven, casualised, anomic conditions of the current American workplace at least as effectively as Charlie Chaplin did in Modern Times. And what was that? A popular film. One of Scruton’s monotonous complaints is that the young are wilfully deaf to their ‘fathers’. They hear but do not listen. But Scruton, too, has stopped his ears. Could any ‘intelligent person’ who listened to ‘Daysleeper’ seriously maintain that it is ‘totally inarticulate’, or that it is ‘brutal’? Any number of objections could be brought against REM, as they could against Bob Dylan, that other darling of sad professors, but there is certainly more to the band than meets the jaded ear of Roger Scruton.

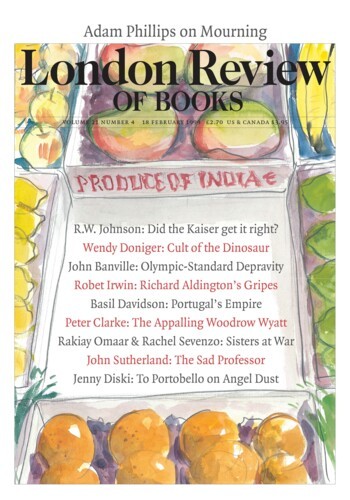

Send Letters To:

The Editor

London Review of Books,

28 Little Russell Street

London, WC1A 2HN

letters@lrb.co.uk

Please include name, address, and a telephone number.