Macaboy is at his workbench, and in the flow of his rituals he might be a priest at an altar, except that he hasn’t a stitch of clothing on. There is an early June heatwave. His skin glistens like a space suit. His balls are drawn up tight with work.

He is making a flush door. This is to be the Prince of Doors. A pure door, an essence. First principle: Plywood sucks. Second law: Veneer is Nixonian – all cover-up. The door is being joined from the pieces of aged two-inch walnut that Macaboy chose at Medary’s, which will face the eye of the beholder as naked as Macaboy was at birth and is now. The door will be heavy in the best sense, like the facial expressions of Humphrey Bogart – tough, authentic, mysterious. Its design will follow a classic tradition: the stiles and rails are already trimmed, mortised and tenoned, and slender wedges to lock the tenons lie ready on a tray on the bench, like slivers cut from a small wheel of cheese and laid out for drink time. There will be an extra rail at the waist, so there will be upper and lower panels. But these are to be as thick as their frame – it will be a flush door, as safe as Hoover Dam – and the beauty will be in the dance of grains, not in the play of highlights that comes from piling on frills. There’ll be none of your whorish bevels or moulding, no panel freak’s chamfers or astragals or bolections or cocked beads. Just one perfect surface on which the statements of nature will fill the eye, as they do in a seascape. But this great simplicity calls for precisions as confining as those of certain great complexities on which human life hangs, such as microcentimetrically tolerant Rolls-Royce airplane engines, and this afternoon’s task may be the most exacting of all. He is gluing up the upper panel: six slim hexahedrons to be forced together, perfectly squared, without the least winding or washboarding – flat as a sheet of plate glass.

John Hersey, The Walnut Door

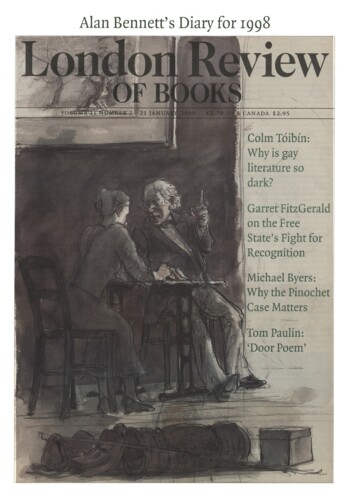

three four

knock at the door

– imagine the door as subject

no mystery

just a coathanger

a formal object

on which for some reason

you’ve to drape its own history

– how it began

– is began better than started?

– began as the flap on a tent

made out of cloth or hide or felt

like the tent itself

– then the door proper

made of what’s termed

rigid permanent material

that came about si-

multaneously with architecture

– various big squat

round or high

buildings whose doors

were made of stone or bronze

and had heavy hinges

whose pivots

were coated in lard or oil

so they didn’t scringe

– notice though how among several

definite objects

we’ve got felt and lard

so on one level

this must’ve something to do

with Joseph Beuys

a heroic artist like James Joyce

except he’s more like Icarus

because the young Beuys – 19 –

was a Stuka pilot in the Luftwaffe

a prince of the air yes

conscripted by darkness

like Satan

but a no-sayer to the Nazi cause

– unstrapped and unbuckled

he flew into a black smoky clatter

– Soviet ack ack that sounded

like munching apples in church

– his plane bucked and lurched

then crashed hard

into the Caucasus

– young Joseph lay crushed

in the smashed cockpit

– deep snow windhowl emptiness

no search party no one

till a voice said voda

and made him sip steelcold water

– two Tartar tribesmen he’d known

back at the airbase

– Du nix njemcky

du Tatar

took him into their tent

where they rubbed his body all over

with grease and soft lard

wrapped him in layers of felt

and strapped them tight

in the tent

a dense smell of cheese grease milk

he was out of it for a fortnight

then they strapped him to a sledge

and lugged this felt parcel

to the German lines

– a pissed-off sentry

mangy and frostbitten

in the lichened daylight

pointed to a flap

on the hospital tent

– inside a smell

of disinfectant and crap

but as they lift him into that orderly hell

it’s another threshold another liminal

bar another edge

I meant to take as part of this subject

– if it is a subject

for twenty-five years after

Joseph Beuys was lifted

from his wrecked Stuka

and enveloped in felt

I’m reading Heaney’s latest book

– Door into the Dark

in a bed and breakfast

a creaky Georgian farmhouse

maybe near Limerick

somewhere anyway in the west

– it’s so far back

it’s like the year nought

and why should the place matter?

why name what patch of ground

now thirty years later?

I’ve stepped back into the dark

to catch the hammered anvil’s shortpitched ring

and to take the stress

of that precise shortpitchedness

how it rings

– stopped short abrupt

how it sting sting stings

like bullets in a tunnel

its thingness

like sparks in your eardrum

part of a pattern

of foreclosed sound

almost as if the bank’s stepped in

and put a bar

on any right of redemption

or else that shortpitched ring

might be the underground creak

of the state’s static timbers

or again it might be

a type of ontological

split that also heals

– that is anneals

it all back together

like some phantom particle

that both splits and doesn’t split

– it’s a civil war trope

that maybe cancels hope

or does it?

I couldn’t frame that question

– not as a youth not then

but the way the eye bends

to the big black anvil

horned as a unicorn

and square at one end

– this was a door sill

one of the very first

and because reading’s a social

always a social act

I began to be nervous

– there was something inside

that was also outside

something on the loose

– I was ill all that week

– ill with a heavy bronchitis

so when I switched off the light

the darkness of the mouldy bedroom

was too absolute too thick

like the essence of night

that can frighten you sick

– I imagined a door

disguised as a bookcase

the eight o’clock walk

to the greased trapdoor

then that hidden chalk

mark on the inside

of Tom Paine’s cell door

– it was shut and that saved him

from the death squad in the corridor

– but these are a young skite’s

callow fears

I’ve been here before

and later grown weak and flustered

in front of a blistered door

– the door

of an empty farmhouse

between Ballyeriston and Maas

– inside a stink of damp and disinfectant

on the table – bare table –

one half-empty

bleared bottle of Powers

– only a half bottle

like a kind of subtraction

or like a tomb gift

from the dead to the living

a bottle that didn’t imply

any human connection

– it’d never be lifted

to the rim of a glass

outside banal and forever

the blistered paint on that door

was like bladderwrack

ready to be popped

ready to pop off

like the old cattle farmer

who worked a hundred acres

and tried to live on air

– but no turfstack

no beasts in the back

– that poverished field –

no halfdoor like a welcome

in the cottage next the barn

– no harm

but this is losing the plot

because each and every door’s

what you beat your head against

– a door is more than a fence

it’s complete denial

and even Ghiberti’s great bronze doors

the Porta del Paradiso

on the Baptistery in Florence

– doors that took twenty years

to shape and cast and hang

– even those enormous doors

overwhelm as objects

as foursquare function

and can never be as pure as song

– they belong to epic

like the grating hinges in Milton

or the crazy door of the jakes

that Bloom kicks open

a jerky scraky shaky

door

that because we ken

a particular pong

– mouldy limewash and stale cobwebs

it’s like coming home

and knowing it is home

– and so Bloom came forth

from the gloom into the air

Send Letters To:

The Editor

London Review of Books,

28 Little Russell Street

London, WC1A 2HN

letters@lrb.co.uk

Please include name, address, and a telephone number.