From my rotting body, flowers shall grow and I am in them and that is eternity.

Edvard Munch

I Landfill

In ways the dead are laid

or how

they come to lie

I recognise myself

insomniac

arms

angled

or crossed:

children in skull caps

soldiers with hobnailed boots

or sandals placed like gifts

beside their feet

priests at the gates of death

or afterlife

their vestments stained with malt

and carbon

fingers rinsed

with camomile

or honeyed meadowsweet

resemble me

laid sleepless by your side

as if there were something else

some chore or rite

to be completed.

Once

in rural Fife

and Angus

farmers held

one acre of their land

untilled

unscarred

to house this mute

concurrence with the dead

choosing from all their fields

one empty plot

that smelled or tasted right

one house of dreams.

They walled it in

and called it Gude Man’s Land

or Devil’s Piece

and some would say they guessed well every time

knowing the gist of the thing

the black in the green

of stitchwort

though I can’t believe they thought

that tremor in the grass

on windless days

was devil’s work:

yet

where they found old bones

or spills of blood

where birdsong ceased

and darkness stayed till noon

they recognised some kinship with the dead

with bodies they had found

in nether fields

the faces soft

still lifelike

grass and roots

decaying in the gut.

They guessed it well

divined its mysteries

and left it to the pipistrelles

and jays.

When I was five

or six

– I can’t recall –

the land for miles was sick with foot and mouth

and grateful of the work

my father

travelled the length of the county

digging pits

for slaughtered herds.

On farm after farm for miles

in the paling light

he worked all day

and far into the dusk

then caught the last bus home

his shirt-sleeves stitched

with quicklime and dust.

That was the year our neighbour

Agnes

died:

her body thick with growth

the blackness

tight between her lips

like needlework.

I thought she had been touched by foot and mouth:

a fog of disease that spread

on our spoons and knives

and bottles in the playground

stopped with cream

and waited for my father to begin

unravelling

like twine.

I stood in the kitchen and watched

while my mother

fixed him his tea

amazed at how lonely he looked

how suddenly tired

a blur of unspoken hurt

on his mouth and eyes

and I loitered all afternoon

while friends and strangers

emptied the house our neighbour had kept intact

and still as a chapel

heavy with the scent

of Windolene.

They worked all day

intent

and businesslike

clearing the rooms

the wardrobes

the silent cupboards

folding her winter coats and summer shawls

packing her shoes in boxes

her letters

her make-up

and bearing it away

to other rooms

time-soiled

infected.

I scarcely recall:

there was something I overheard

a sense of the ditch

and the blind calves laid in the earth

a nightmare for weeks

of gunshots

and buried flesh

yet still

when I lie naked in our bed

I sense my father waiting

and I shift

like someone in a dream

so he will turn

and go back to the fire

and let me rest.

II Two Gardens

When we came it was couch-grass and brambles,

colonies of rue amongst the thorns,

a leafless shrub that smelt of creosote

and simmered in the heat.

I liked it then. I liked its stillnesses:

the ruined glasshouse packed with honey-vine,

the veins of ash, the pools of fetid rain.

Sometimes we found strange droppings by the hedge:

badger or fox, you said; but the scent was laced

with citrus, and I kept imagining

a soft-boned creature stalled beneath the shed,

strayed from its purpose, wrapped in musk and spines.

In spring we set to work; we marked our bounds

and found the blueprint hidden in the weeds,

implicit beds, the notion of a pond.

You sifted out the shards of porcelain,

illumined willows, scraps of crescent moon;

I gathered clinker, labels, half a set

of Lego.

As I watched that summer’s fires

I wondered what was burning: living bone,

pockets of silk and resin, eggs and spawn,

and, afterwards, I saw what we had lost:

surrendered to our use, inanimate,

the land was measured out in bricks and twine,

a barbecue, a limestone patio.

The work is finished now; but after dark

I feel the creatures shivering away,

abandoning an absence we accept

as natural: the unexpectant trees;

the silence where the blackbird vanishes.

At times the ghosts are almost visible

between our trellises and folding chairs:

just as old harbours sometimes reappear

through fog or rain, or market towns dissolve

to gift us with a dusk of shining air,

the garden we destroyed is almost here,

nothing but hints and traces, nothing known,

but something I have wanted all along:

a thread of pitchblende, bleeding through a stone,

or snow all morning, cancelling the lawn.

III Gude Man’s Land

There was something I wanted to find,

coming home late in the dark, my fingers

studded with clay,

oak-flowers caught in my hair, the folds of my jacket

busy with aphids.

I slept in my working clothes

and walked out in the buttermilk of dawn

to start again.

Sometimes I turned and saw him through the leaves,

a face like mine, but empty of desire,

pure mockery, precision of intent,

a poacher’s guile, a butcher’s casual charm.

The house filled slowly with the evidence

I carried home: old metals, twisted roots,

bottles of silt and water, scraps of cloth.

My neighbours passed me on the road to kirk

and thought me mad, no doubt, though I could see

their omnipresent God was neither

here nor there.

Who blurred the sheep with scab? Who curdled milk?

Who was it fledged the wombs of speechless girls?

They knew, and made their standard offerings

and called it peace. But he was with them still.

His secret thoughts were written in their veins,

and when they dreamed of music, it was his,

and when I dreamed, I fed him in the dark,

wifeless and quiet, lacking in conversation.

He knew what I wanted; I knew what I would not dare;

lying alone in the darkness, burning with fever,

walking the fields in the rain, at home and lost,

the feel of his recent warmth

on the tips of my fingers,

the taste of his body minted in the wild

patches of grass that quickened along the walls

or ran in circles round the nether field,

absorbing the daylight,

informing the guesswork of children.

IV Otherlife

Be quick when you switch on the light

and you’ll see the dark

was how my father put it:

catch

the otherlife of things

before a look

immerses them.

Be quick

and you’ll see the devil at your back

and he’d grin

as he stood in the garden

– cleaning his mower

wiping each blade in turn

with a cotton rag

the pulped grass and bright green liquor

staining his thumbnails

and knuckles.

He always seemed

transfigured by the work

glad of his body’s warmth

and the smell

of aftermath.

He’d smoke behind the shed

or dart

for shelter under the eaves

the fag-end

cradled in his hand

against the rain:

a man in an old white shirt

a pair of jeans

some workboots he’d bought for a job

that was never completed.

And later

after he died

I buried those clothes in a field above the town

finding a disused lair amongst the stones

that tasted of water

then moss

then something

sharper

like a struck match in the grass

or how he once had smelled

home from the pit

his body doused in gas

and anthracite.

I still remember

somewhere in the flesh

asleep and waking

how the body looked

that I had made

the empty shirt and jeans

the hobnailed boots

and how I sat for hours

in that wet den

where something should have changed

as skin and bone

are altered

and a new life burrows free

– sloughed from a slurry of egg-yolk

or matted leaves

gifted with absence

speaking a different tongue –

but all I found in there was mould and spoor

where something had crept away

to feed

or die

or all I can tell

though for years I have sat up late

and thought of something more

some half-seen thing

the pull of the withheld

the foreign joy

I tasted that one afternoon

and left behind

when I made my way back down the hill

with the known world about me.

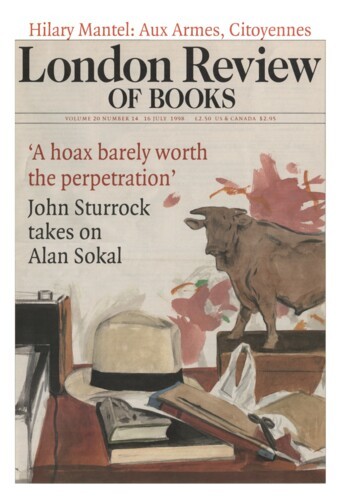

Send Letters To:

The Editor

London Review of Books,

28 Little Russell Street

London, WC1A 2HN

letters@lrb.co.uk

Please include name, address, and a telephone number.