Remembering the story of a man

who left the village one bright afternoon,

wandering out in his shirt-sleeves and never returning,

I walk in this blur of heat to the harbour wall,

and sit with my hands in my pockets, gazing back

at painted houses, shopfronts, narrow roofs,

people about their business, neighbours, tourists,

the gaunt men loading boats with lobster creels,

women in hats and coats, despite the sun,

walking to church and gossip.

It seems too small, too thoroughly contained,

the quiet affliction of home and its small adjustments,

dogs in the back streets, barking at every noise,

tidy gardens, crammed with bedding plants.

I turn to the grey of the sea and the further shore:

the thought of distance, endless navigation,

and wonder where he went, that quiet husband,

leaving his keys, his money,

his snow-blind life. It’s strange how the ones who vanish

seem weightless and clean, as if they have stepped away

to the near-angelic.

The clock strikes four. On the sea-wall, the boys from the village

are stripped to the waist and plunging in random pairs

to the glass-smooth water;

they drop feet first, or curl their small, hard bodies to a ball

and disappear for minutes in the blue.

It’s hard not to think this moment is all they desire,

the best ones stay down longest, till their friends

grow anxious, then they re-emerge

like cormorants, some yards from where they dived,

renewing their pact with the air, then swimming back

to start again. It’s endlessly repeatable

and soon forgotten

decaying as most things do

in the sweep of time.

I watch them for a while, then turn for home,

still unconvinced, half-waiting for the day

I lock my door for good, and leave behind

the smell of fish and grain, your silent fear,

our difficult and unrelenting love.

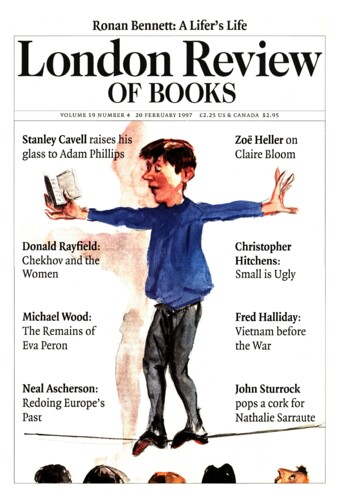

Send Letters To:

The Editor

London Review of Books,

28 Little Russell Street

London, WC1A 2HN

letters@lrb.co.uk

Please include name, address, and a telephone number.