I was travelling in Illinois when I first heard some beefy local pol utter the profound Post-Modern truth that ‘Politics is showbiz for ugly people.’ Yes, you too may be a mediocre, flaky-scalped, pudgy sycophant. But, with the right ‘skills’, you also can possess a cellular phone and keep a limo on call and ‘take meetings’ and issue terse directives like ‘I want this yesterday, understand.’ Unfortunately, the women you meet in the politics biz will tend to be rather too much like yourself. But, hey, bimbos can be rented! And won’t they just be impressed to death when you pass them the bedroom telephone extension and it’s the Prez talking.

By ‘politics’ of course, I don’t mean the conflict of ideas and interests and interpretations. But then, who does these days? I mean the sump of images and soft money and poll-meisters and consultants: the spongy, protean surface upon which one can grow tendrils like Mr Morris and, for the matter of that, Mr Clinton. The President is justly renowned for dropping old friends like hot bricks if they threaten him with embarrassment, but he clung to Morris long after he had been exposed as a sleazebag, and still speaks of him in terms of lip-biting regret. In fact, let’s have Bill’s dust-jacket endorsement of Dick in full:

I think he is, first of all, brilliant, tactically and strategically. Secondly, with me he’s always been very straightforward and honest, the bad news as well as the good and, if possible, the bad news first. Thirdly, he knows how I think, and he knows what I will do and what I won’t do. Fourthly, he’s full of new ideas all the time. And, finally, we’ve been together so long that he not only understands me, I understand him.

This says a good deal about both men. One is a big Babbitt; a Babbitt on a global scale. The other is a Babbitt more in the Osric mould: a tenth-rater who knows how to make himself useful and has a concept of the big break or the main chance. Morris knew Clinton when the latter was a struggling governor of a small state, and was able to do him a number of little services. (He often boasted of procuring girls for him on out-of-town trips.) But, as a toady, he knew his station and was not surprised or hurt to be put on hold when he was no longer required. Indeed, he felt happier going back to work for uncomplicatedly conservative clients like the senile racist Jesse Helms. But in October 1994, ‘my pager vibrated its summons again.’

The President: ‘I want you to do a poll for me. I’m not satisfied that I know how to handle what the Republicans are doing to me. I’m not getting the advice I need.’

The Republicans? I was one of them. My candidates in that year’s midterm election included Republican Massachusetts governor Bill Weld and Mississippi senator Trent Lott, both seeking a second term, and Don Sundquist of Tennessee and Tom Ridge of Pennsylvania, two Republican gubernatorial candidates.

‘Mr President, that would be a conflict of interest. If you want me to do political work for you, you’ll have to ask me after the November election.’ That’s what I didn’t say. You don’t say no to the President. Besides, I needed the fix too badly. I agreed to do the polling.

Morris is a second cousin of Jules Feiffer and also of Roy Cohn. What a gene-pool, to have produced America’s most mordant radical cartoonist and also its leading fascist closet-case and McCarthyite spear-bearer. Morris doesn’t mention Feiffer at all in this book, but he does tell a few wide-boy stories about Cohn, which show a mingling of affected shock and vicarious admiration. He doesn’t possess the talent or wit of the one or the ‘ruthlessness’ (keyword) of the other, but his awareness of his own limits is exactly what makes him such a good subordinate. For him, the perfect boss is someone driven and insecure; someone who thinks he is the manipulator but can be manipulated; someone who strikes a bold attitude and then instantly checks the mirror or the opinion polls. If you are fated to be Osric, then count yourself lucky to toil for a weak and vain king.

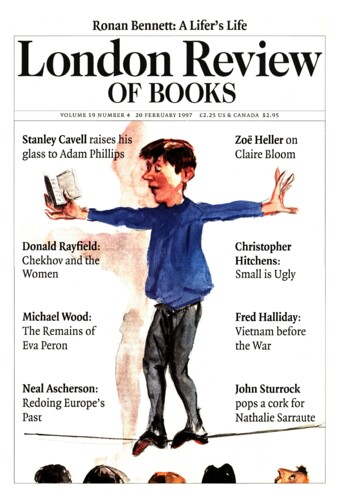

During the course of his breath-catchingly trite and boring inaugural speech this past January, the President came to a line which reeked of midnight oil. He bore down on it, emphasised it, enunciated it with portent and paused after it for effect. ‘Nothing big,’ he intoned, ‘ever came from being small.’ The vague indecency of the line, in the context of the utterer himself, has since warmed many a Washington hearth. But the stress laid on it was suggestive in quite a different way. More than any President of modern times, Clinton has concentrated on the micro-effect, and has hired micro-managers to assist him. In the course of the last campaign, he embarked on a barnstorm of what might reasonably be termed trivial pursuit. Granted a large audience and a grand podium, he would choose to speak of the importance of school uniforms, decency on the Internet (thanks a lot), curfews for teens or anti-smoking drives. Morris was the moral author of this ‘concept’, both as a small man and as a tiny mind:

I grew up with a chip on my shoulder. Born in 1947 three months prematurely, I began life weighing only two pounds, 11 ounces, and spent my first three months in incubators, untouched by anyone, even my mother. Only after years of therapy did I begin to understand how this early deprivation affected my personality thereafter. I learned that much of my need to bond closely with people came from that experience.

Whereas Clinton, as we now have been told ad nauseam in his own voice, was a fatso in big jeans and a lonesome mainliner of Big Macs at least until he realised that power could also mean sex. The compromise between the whale and the shrimp is set down here as a deliberate and poll-driven menu of relentlessly ‘small-bore’ and ‘bite-sized’ ideas, herded together under the lazy heading of ‘our values agenda’. Remember ‘a small town called Hope’? This was a parochial manner, allied to a strategy for power where only the donors, and the donations, were on anything like a grand scale. Without those arbiters of soft money and hard bargains, and the vast off-the-record treasury that they furnished, Dick Morris would have gone to work for somebody else.

As with all small men who are allowed to infest the throne-room, Morris develops a mild form of megalomania. It is ghastly to read him when he takes credit for leaving the Bosnians to their fate, or for covering up for Boris Yeltsin, or for liberating Haiti, or for building a bridge (to coin a phrase) to Richard Nixon. It is ghastlier still to reflect on the germ of truth that lurks in each conceited anecdote. Of the White House staffers who did not trust him and with whom he wants to settle accounts, the most prominent two – Chief of Staff Harold Ickes and Senior Policy Adviser George Stephanopoulos – have since departed the scene. Ickes was fired in humiliating circumstances after years of canine loyalty, and Stephanopoulos had had enough for other reasons. But neither man received any Presidential encomium, even of the conventional and hypocritical sort, to rank with the sober melancholy with which Clinton bid adieu to the disgraced and exposed Morris. Moreover, our Dick seems (and again not just on his own testimony) to have evolved quite a relationship with the First Lady. It had, indeed, been Hillary’s idea to get Morris back on the team after Clinton’s reverse in Arkansas in 1979. She it was who snatched up the phone and made that cheap pager vibrate its thrilling summons. ‘Bill needs you right now,’ she breathed. I mention this only because half the liberal reviewers in America believe that the First Lady is secretly on their side, and the other half are so unschooled that they will unironically blame the faults of The Leader on ‘bad advice’ and ‘bad advisers’. If only the Tsar knew ...

Morris will pass into the ephemeral record of photo-op politics as the originator of the concept of ‘triangulation’. This is a small-minded, not to say simple-minded concept, with sinister implications. The essence of it is a kind of gutless ju-jitsu, where you borrow the strength of your opponent to use against him, before unctuously handing it back again. Is he, for example, a racist? And is his message playing well in the shopping malls? Then meet him halfway and have him off-balance. The implications of this style are not necessarily trivial. Morris tells us that he urged prayer in schools, an end to busing, a moratorium on immigration and a national anti-union law. Had the Dole-Kemp ticket ever registered any kind of pulse, we would probably not have been spared any of these fine initiatives. And, since Morris was once caught sharing his White House poll data with Bob Dole’s office, perhaps the ‘triangulation’ even went that far.

Like other consultants, I am often called a mercenary, which is fair enough, though I sometimes get involved for free in hometown Connecticut races just because it is fun to help. I have worked for both Democrats and Republicans, which strikes some people as the height of cynicism. I would refute that.

Which brings us to another aspect of this scandal. In his Uriah Heep-like acknowledgments, Morris warmly thanks Random House editors of the stature of Harold Evans and Jason Epstein. Never mind for the moment that Random House doesn’t employ a copy-editor who knows the use or meaning of the word ‘refute’. Here is a ‘book’ for which two and a half million dollars were paid up front, in a surreptitious agreement of which the President knew nothing. All toadies have their revenge some day, for those moments when they were dismissed too easily or too casually. Random House colluded in this unprincipled bargain, but it did not get value for its outlay. About the slag heap of dirty-money revelations that currently blocks the view of (and perhaps even the view from) the Oval Office, Morris is resolutely ill-informed and uninformative. Can it be worth even half a million of anyone’s money to read that ‘polls’, as employed by Morris, ‘are not the instrument of the mob; they offer the prospect of leadership wedded to a finely-calibrated measurement of opinion.’ We could work out for ourselves that polling is a means by which the élite gets the first chance at shaping mass opinion: the prerogative of the oligarch throughout the ages. No amount of pseudo-populist boilerplate can occlude this salient fact. For one thing, note the cost, and the titanic budget. Once you have done the polls, you and your fellow ‘consultants’ get to design the ads. Morris boasts of how he got Clinton to empty the vaults here:

In 1992, Clinton and Bush each spent about forty million dollars on TV advertising during the primary and general elections. In 1996, the Clinton campaign and, at the President’s behest, the DNC spent upwards of eighty-five million dollars on ads – more than twice as much! [Exclamation mark his: courtesy of Random.]

‘DNC’ here stands for the Democratic National Committee: the body which won renown when its Watergate offices were burgled by the Nixon gang. As I write, it is under multiple investigation for soliciting and spending heaps of illegal cash; much of the boodle laundered through the most umbrageous foreign bag-men, and in ways that might have caused even the original Tricky Dick to purse his lips a little. As with Nixon, too, the alternation between constant polling and continual reliance on fat cats represents the worst of collectivism and the worst of ‘free enterprise’. Morris tells us that, even as the money from big-tab contributors was rolling in, he ordered Clinton to take a camping holiday rather than a Martha’s Vineyard one – in order to look more like a man of the people. And Clinton fell for it. And Morris was able to come up with ‘numbers’ that seemed to confirm the wisdom of the ‘concept’. This consoled the President for a vacation that he had not wanted and had not enjoyed. But the finest hour in the life of either man is that magic one when they can say that they fooled some or most of the people some or most of the time.

This is probably the only saying of Abraham Lincoln that Morris could be trusted to recall. So it’s diverting to read Morris’s account – clearly verbatim, from notes – of a conversation he had with Clinton on the specified date of 4 August 1996. The subject was the President’s ranking in history, or at least the history of his office. Morris proposed that there were only five ‘first-tier’ Chief Executives, Washington, Jefferson, Lincoln, Wilson and Franklin Roosevelt: ‘Presidents who did great things but also did them in great times. I don’t think you can get onto the first tier unless you have the right backdrop.’

‘You mean a war or something like that?’ he asked.

The vulgarity and cheesiness of the subsequent ‘ratings’ discussion is almost the only truly gripping thing in the book, and is one of the few passages that could not have been written by some sort of machine. How odd to have left out Truman, especially since the two men were talking only a day or two short of the anniversary of Hiroshima – red-letter date in the evolution of tough-minded New Democrats. Still, nice to have left Honest Abe near the pinnacle. (A few months later, the Clintons were to be caught selling nights in the White House Lincoln Bedroom to especially generous campaign contributors: one of the few moments in the unfolding money scandal when ordinary voters got the point and evinced wholesome populist disgust.)

As I write this, Morris’s influence in the White House is still pervasive. The Wednesday Night Strategy Meeting, set up by Clinton and Morris as a sort of covert conclave kept hidden from the rest of the staff, has persisted into the second Administration. That inaugural speech, during which circling birds fell stunned from the sky, was mainly ‘written’ by Donald Baer, a Morris placeman. And the first big initiative of the new Presidency was a stirring call for increased food safety. Mrs Morris, meanwhile, has rejected the glutinous plea for a reconciliation that is tacked onto the opening of this book, and announced that she is washing Dick right out of her hair. Having felt sorry for her, I now envy her. She can get rid of him. We can’t. One of Morris’s less gifted therapists must have suggested that he read ‘If’, because on the title page appear the lines:

If you can meet with Triumph and Disaster

and treat those two impostors just the same ...

I suppose it could have been worse. He could have declaimed about walking with kings and not losing the common touch. But he has never had a triumph, and a feather bed of public and private patronage has cushioned him against disaster, and he doesn’t have the self-knowledge to realise that the impostor is himself.

Send Letters To:

The Editor

London Review of Books,

28 Little Russell Street

London, WC1A 2HN

letters@lrb.co.uk

Please include name, address, and a telephone number.