Near the edge of town where the graveyard opens out

under white sky, a girl stands on a wide porch, looking

at the cottonwood trees, her fingers intertwined behind her head.

A boy on a ship reads a letter, waits and walks

under white sky across the wide deck, looking

at the sea and listening for the wail of kamikazes.

He writes a letter: It is silent before dawn. I often walk

around deck. I wake at five o’clock –

he listens for the wail of kamikazes –

to shower and shave alone. Thank you for the mirror.

Below deck, the others sleep until six o’clock, deep

in the ship’s quiet belly; he walks the deck until dawn.

He showers and shaves alone, his face foggy in the mirror,

thinking of the curving sea – how round the world is –

deep in the ship’s silent belly. The sea is often calm

and blue. The girl leans back in a bamboo chair

thinking of the curving sea – how far away the ship is,

as she shuffles the pages of a letter. Looks at his photo

in the blue afternoon. She leans back and brushes her hair,

cuts out newspaper photos of soldiers. Separates them,

looks through the paper, shuffles the photos

into stacks. Those who’ll come back. Those who won’t.

She collects them for mothers of soldiers. Separates them,

frozen in time, their golden buttons gleaming.

Clips together the stacks – those who came back, those who didn’t.

She paints a bowl of flowers – chrysanthemums for death –

frozen in time, their petals gleaming.

Or walks the graveyard in winter where tombstones rise

(brings a new bowl of flowers, chrysanthemums for the dead),

rise up through the snow like icebergs, her ancestors there in rows.

She walks the graveyard in a long black coat,

arms folded across her chest, names the dead, waiting.

There under the ice and snow, her ancestors lie in rows,

waiting for afterlife to begin. Dressed in Sunday best.

Arms folded across chests, blessed and waiting.

A grandmother beside a veteran – without a tombstone yet,

waiting for afterlife to begin. Dressed for Sunday’s rest.

Waiting for the living to count their money, to name him.

A grandmother beside a veteran, without a tombstone yet.

A man with a hammer and chisel will chip his name,

after the living have counted their money, have told him –

just a block of local yellow stone. Before the girl walks home

she breaks an icicle, chips her name into the snow

under the cottonwoods. On board the boy is writing

on a pad of yellow paper. The girl walks home

watching mist rise from the mouths of canyons

through the cottonwoods, while on board the boy is writing:

Further off on the horizon, a ship blooms red, fades into night.

He watches smoke rise from mouths of cannons.

One morning, after weeks of C-rations, he waits

as hundreds of grapefruits tumble out onto the deck;

he plunges his thumbs into one, drinking.

The morning’s weak light, the crashing sea –

beautiful yellow suns in the swirling fog –

he plunges his thumbs into another one, drinking

the sweet blood, letting the fruit fall.

From the porch she watches the sun set into fog,

thinks of the edge of town where the graveyard opens out,

how the sky is red as sweet blood, how winter light

falls through cottonwoods. How the living intertwine with the dead.

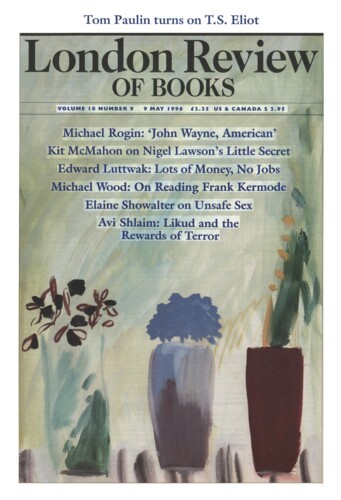

Send Letters To:

The Editor

London Review of Books,

28 Little Russell Street

London, WC1A 2HN

letters@lrb.co.uk

Please include name, address, and a telephone number.