The view that things are getting worse seems to be on the increase in Russia. In June, lzvestia published the results of a poll conducted by the All-Russian Centre for the Study of Public Opinion – said to be the best organisation of its kind – in which 58 per cent of respondents thought that they were better off before Gorbachev came to power; two years ago only 45 per cent believed this.

Polls are notoriously devious. The questions are not too blunt but too sharp. The question, ‘Do you live better now than before 1985?’ would almost certainly elicit a negative response from most Russians, if they were thinking narrowly of their material well-being and of the power and reputation of their country. But if one were to add, ‘Do you think this a reasonable price to pay for greater civil liberties? For the possibility of democratic government? For a more open culture?’, then the terse pessimism of the simple answer might at least be modified.

There isn’t much that can be done about the inherent limitations of foreign corresponding, which – in Russia as in other places – involves a risk that the realities of life will come to be seen exclusively in terms of the rhetoric of political and other interest groups, statistics, quotidian grumbling, commonplaces, distortions and (usually contradictory) insights. But the offer of a long weekend in a provincial Russian town, staying with a friend’s relatives, promised to extend a little the boundaries of my own understanding by enabling me to observe for more than an hour or so how Russians live now, a few months before they must begin to choose how their country is to be governed.

The town was Yaroslavl, one of the centres of faith and power in medieval Russia, a considerable place in Tsarist times because of its position on the Volga between Moscow and the great merchant city of Nizhny Novgorod. Its riches are still on display in the fine, uncared-for mansions which line the bluffs above the river, in the many large churches which remain (more were destroyed), in the wealth, visible still, of the monastery within the town and the nunnery outside it, and in the artefacts in the town’s museums. The friend – my closest Russian friend – was Natasha, a woman of nearly seventy who teaches at Moscow State University’s sociology faculty, a former Communist who was party secretary of her department until in 1990 she followed Yeltsin in breaking with the Party, and became an enthusiastic democrat. Now, like many in the intelligentsia, she has adopted a despairing liberalism tinged with hostility to the West.

Natasha’s relatives are, like her, members of the intelligentsia. Sasha, who met us at the station after the five-hour trip from Moscow, is a man of about forty, angular and awkward, a ‘docent’, or senior researcher, in particle physics at Yaroslavl University. At first he held me at a courteous distance as we took the crowded bus through the centre, across the industrial district and out to the vast suburb, built up since the late Fifties, where he lives with the rest of the family: Tanya, his wife, an administrator at the University; her father Nikolai, a retired Soviet Army colonel; and the couple’s two children, who were staying with their grandparents in the country. They live in what is now known as ‘Khrushchoba’, a usage which combines trushchoba, the word for ‘slum’, with Khrushchev, who was General Secretary when this type of apartment block was built. They are everywhere across the former Soviet Union, from Lithuania to Kirghizia: about eight storeys in brick, with flats – in my limited experience – of identically cramped dimensions. This flat had one room of 12 square metres, another of twenty perhaps, a kitchen of five, a tiny bathroom and toilet and a cupboard which Nikolai had fitted out as his workroom and where he sat much of the time on a stool, either at work or reading the newspapers, coughing through his papirosi.

Russian hospitality is complete and coercive, self-sacrificing and non-negotiable. I had with me my seven-year-old son, Jacob. We were given the smaller of the two rooms as our bedroom, while Sasha lodged with friends nearby, and Natasha, Tania and Nikolai slept in the larger room. No question of a hotel or of my staying with neighbours. Knowing their poverty, I had brought a bag of food. It caused awkwardness until it was rationalised as my having to feed a young son of finicky tastes. Awkwardness was everywhere at first. Natasha’s good humour and energy could not obscure the enormous defensiveness and embarrassment Sasha and Tanya felt at their poverty. They knew, since they watched TV, and Sasha had been at symposia in the US and Italy, that their living standards were far below mine. Together they make less than $150 a month. Sasha get about $60 or $70 as a senior researcher, Tanya about $30 as an administrator; Nikolai’s army and other entitlements come to about the same. They pay a very low rent – about $5 a month – but they have very little to show for it. They have no car. The furniture is battered and torn. The stove is old, the bathroom fittings stained. Only the TV is new – a Panasonic.

As I was trying to play football with my son outside on the evening of our arrival, Sasha insisted on telling and retelling the (impressive) tale of Soviet nuclear physics, of its being equal to nuclear physics in the West, of the success of the Russian Academy of Sciences in sustaining the main scientific institutes, of the excellence of Russian education, of the desire of his colleagues in other former Soviet states to be linked integrally with Russia once again – so bereft were they now that the central engine of their scientific development had been removed. He said he did not like America. He had found it vulgar; ironically, he had gone to a conference in St Petersburg, Florida. I was reminded of my grandfather coming back from a stay with his sisters, who had emigrated to Seattle in the Twenties, and finding in the Scottish fishing village where we lived a haven of simple virtues after the crass materialism of the late Fifties in America. It is in opposition to Western materialism and false sophistication, as they are perceived, that many thinking Russians now construct their cultural defences. Gone – and long gone for the intelligentsia – is the propagandist belief that socialism could or would materially surpass capitalism; come up is an older view that high standards of living are pursued and attained at the expense of humanity, charity and simplicity. This was a commonplace of 19th-century Russian writing: that the Westerner, or the Westernised Russian, might be efficient and progressive but was shorn of other qualifies – soul, endurance, intuitive understanding.

Tanya and Sasha appeared to be able to rub along in their cramped conditions and they treated her father with respect, though not with deference. The hostages had already been taken by Chechen guerrillas in the southern Russian city of Budennovsk and, while I was with the family, we watched heart-rending newsreel of the sick, the elderly and infants being held at gunpoint by masked men. Nikolai growled continually; he was in favour of storming the hospital and was roused to shouts of rage when Sergei Kovalev was interviewed. Kovalev was the Human Rights Commissioner until his resignation in January. He has pleaded for an end to the conflict in Chechnya. He was in Grozny at the height of the bombardment and has sought to whip up world opinion against the war. He has a considerable following, but is also hated. Nikolai said he should not be allowed on the screen; Sasha remained silent; Natasha said he had a right to speak in any case and Tanya said passionately, perhaps thinking of her son, that she was for him. We drank the malt whisky I had brought, kvass which Nikolai made, the bad local beer and vodka. As the drink took hold, the awkwardness slipped away and the fears and hopes were more frankly expressed.

Sasha and Tanya were born into a stable society, in which their careers, especially his, received support and appeared the more secure since nuclear physics was part of what was making the Soviet Union great. On the wall of the room in which my son and I slept was a photograph of Nikolai in his middle years, handsome and smiling, in officer’s uniform, his arm round his young daughter. He told the story – it was polished with use, for it was his self-defining piece – of how, as a lieutenant-colonel, he had led a detachment of troops, clad in protective gear with gas masks, through the aftermath of a nuclear explosion in 1953 at the Totskoye test site; his was the first such group to be subjected to these conditions. ‘There was nothing afterwards – nothing: the trees were like sticks, the animals stripped to the bone.’

Now his son-in-law does not know if either the civil or the nuclear programme can sustain him. To begin with, he praised the Russian authorities for continuing a centre of excellence in physics at Yaroslavl. With drink, he thought it would inevitably close or be cut back: the science budget is being relentlessly whittled away and physics is shrinking back to the main centres. Where earlier he had said that the brightest came to his department, he now complained that many who would have come were going into business – ‘speculation’ as he called it. What would his children be? Scholars like him, he hoped. He still thought of it as a good life. I asked him if things had got better or worse in the past ten years. ‘Worse, of course,’ he said, ‘but there are some good things.’ His university had subscribed to the Internet and he could access works by colleagues in Cambridge and Palo Alto. He had begun to learn English as a result. But the world in which Sasha nourishes these projects is dark and threatening. The next evening, as we were drinking again, he said that two Chechens who lived upstairs had been found hanging in the lift shaft early one morning – losers in a gang feud. Walking down to the Volga to swim, Tanya had said to Natasha that the cheapest produce was often sold by the ‘blacks’ (Caucasian traders), ‘but I don’t go to them. I can’t bear to touch them, even to speak to them.’

The swim in the Volga was a Sunday outing with another youngish family whose seven-year-old, Sergei, was a good playmate for my own son – he was a cool child, not thrown by Jacob’s habit of injecting into his speech an English word, spoken with a Russian accent, for any Russian one he didn’t know. Jacob showed his own cool by walking into the Volga up to his neck with all his clothes on, a feat which made me the object of horrified clucking and hissing by the babushki in the riverbank crowd waiting for the ferry.

The ferry took us across the great brown river to a beach above which stood the Tolgsky nunnery. The legend is that in 1314 Bishop Trifon of Rostov, travelling in the area, had been woken from his sleep on the bank of the Volga to see an apparition of the Madonna, not once, but twice. This miracle had caused him to found the nunnery, which was built up in the 17th and 18th centuries into a fine walled haven, with two large churches in the middle. The Bolshevik period had done for it. In 1928 the remaining priests were chased out, the bells were cut from the towers and broken on the stone below; Tolgsky became a borstal for sixty years. It was returned to Orthodox ownership in 1987 when Gorbachev made his opening to the Church. Mother Varvara, a brisk, round ball of a woman, has powered through the reconstruction. The initials of young criminals and scrawled obscenties can still be found on the faded frescos; a few rusting signs remain. But the larger of the two churches has been repaired and the frescos are still undergoing restoration

Natasha, Tanya, Sasha and I went in to the five o’clock service. We were the only people in the congregation who were not nuns or women workers at the nunnery. A young nun read the lesson in the rapid, unintelligible singsong way they do in the Orthodox service. A priest, still buttoning himself as he came out from behind the iconostasis, led the celebration. I realised my friends knew little more of how to behave than I did. We all stood uncomfortably, watching the nuns, to copy when to sit and stand. Natasha crossed herself and lit a candle before the main icon for her dead husband. The nuns looked at us impassively, the serving women with hostility. Like so much in Russia this was nash –‘ours’ – not for sharing, even if it was the medium through which God was worshipped.

Outside in the heat and the sun, the beach was sprinkled with swimmers and loafers. Those who had no swimsuit swam in their underwear – vast men and women floating on the muddy brown water, their bellies turned up to the sun. The kids scampered and squealed in the shallows. Teenage couples pawed each other and chewed gum. A skinny ‘biznessman’ parked his BMW in conspicuous view of the beach and sashayed down with his girlfriend, dressed in a thong.

The ferry, inactive for the past two hours, suddenly lurched away from the opposite bank, thumped across the river and disgorged a party of nuns with some young seminarians trailing behind them, all carrying bags bulging with supplies. They walked single file along the jetty, past the running children, past the floating parents, past the necking teenagers, past the New Russian couple still sauntering along the beach, and up into the nunnery, once more able to beg for grace for a fallen world.

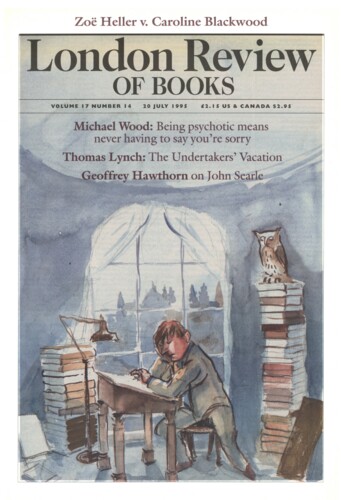

Send Letters To:

The Editor

London Review of Books,

28 Little Russell Street

London, WC1A 2HN

letters@lrb.co.uk

Please include name, address, and a telephone number.