The slates have gone

from that shed in the park

where sometimes the old sat

if they were desperate,

and sometimes the young

with nowhere better to fuck,

and now given some luck

the whole piss-stinking thing

will fall to the ground,

no, I mean

will lift into space,

no evidence left

in its earthly place

of the grey graffiti runes,

the deck of glue,

the bench with broken ribs,

where if things had been different

I might have sat, or you.

This moral won’t do.

Think of Goethe who

all those centuries back

found a pure space like that,

his bench an oak tree trunk,

his view

a plain of ripening wheat

where retriever-dog winds

in a clear track

raced forwards and back

laying a new idea at his feet

again and again,

again and again,

but not one the same,

until he was stuffed full

as one of those newfangled air-balloons

and floated clear

into a different stratosphere.

The oak tree stayed,

its reliable trunk

making light of the sun,

its universe of leaves

returning just as they pleased

each spring, so life begun

was really life carried on,

or was

until a lightning bolt

drove hell-bent

through the iron bark

and split the oak in two.

This moral still won’t do.

You see

one crooked piece of tree

broke free,

escaped the fire, and found its way

into the safe hands of a carpenter.

This man, he liked a shed.

(I should explain:

two hundred years have gone

since Goethe saw

the future run towards him

through the wide wheat plain.)

That’s right; he liked a shed.

He liked the way a roof

could be a lid

and shut down heavily

to make a box,

a box which locked

so no one saw inside

the ranks

of gimcrack bunks,

or heard things said

by shapes that lay on them

with shaved heads,

not even him.

He just made what was ordered

good and sure,

saw everything was kept

the same, each nail,

each duckboard floor,

except, above one door

in pride of place

he carved his bit of tree,

not thinking twice,

into a face,

a merry gargoyle grimace.

This moral still won’t do.

It’s after dark,

and on my short-cut home to you

across the park

I smell the shed

before I see it: piss and glue

and something like bad pears,

and yet,

next thing I know

I’ve stepped inside it,

sat down on the bench

(it isn’t pears, it’s shit)

and stared up through

its rafters at the stars –

their dead and living lights

which all appear

the same to me,

and settle equally.

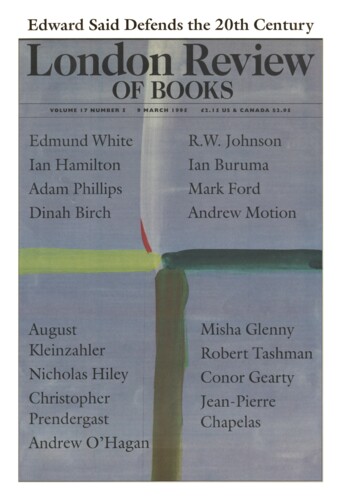

Send Letters To:

The Editor

London Review of Books,

28 Little Russell Street

London, WC1A 2HN

letters@lrb.co.uk

Please include name, address, and a telephone number.