When you draw up a list of famous frogs in the history of the planet, it turns out to be pretty short. There’s the one who was only doing time as a frog, and there’s the one who was nothing more than a small felt glove puppet who went into show-business and hobnobbed with a lot of celebrities in the Seventies. And neither was a frog in the true sense of the word. (Doubtless in the frog world there are only a couple of famous humans, and probably one was really a frog condemned to live in the body of a prince, while the other was just a happy-go-lucky hand-operated puppet that became a celebrity by hanging out with the top frogs in the entertainment industry. But there’s no way of checking on that.)

They may both be green and imaginary, but apart from that the two frogs are very different. The frog-as-prince is the embodiment of a profoundly anti-frog message: to be a frog is to be punished, to be sentenced to a season in purgatory. As with most fairy tales, political correctness is low in the pecking order of story-telling imperatives. The frog-as-puppet by contrast suggests that frogs can be successful, witty, unabashed in the company of international megastars, and above all loved (so long as they’ve got a human hand up their rectum).

That’s one difference. The other is that, of the two frogs, fame came much more readily to the frog-as-puppet. The frog-as-prince, as the anti-hero of a fairy tale, got his name around mainly by word of mouth: he was a frog in the oral tradition. In the age of multimedia communications, the frog-as-puppet made progress a lot more quickly. He started out in television, got a lot of bookings as an entertainer, found himself hosting his own variety extravaganza, appeared in chat-shows and on the cover of magazines, and ended up starring in a number of blockbusting Hollywood movies. From about 1975 onwards, his on-off affair with a domineering, unscrupulously ambitious pig was the meat and drink of gossip columnists. It was the perfect career trajectory, beyond the scope of a fairy-tale hero working in less frenetic times. The frog-as-prince was probably green with envy.

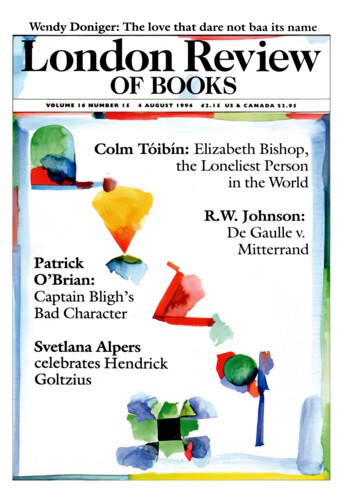

The frog-as-puppet is called Kermit. He is the invention, extension and would have been the pension of Jim Henson, had Henson not died in 1990 at the age of 55, still in the ferment of wildly brilliant creativity that saw him design, name and give characteristics to an Arkful of daft creatures. Kermit is on the cover of this book,* bursting through the plane of white paper as if in symbolic disdain for the printed page on which his fame has never relied.

The full career of Jim Henson reveals that the gulf between the traditions of fairy tale and the self-inventing styles of television culture generally thought to have supplanted them is not as wide as the disparity between the two frogs would suggest. For a start, one played the other in a film called The Frog Prince (1971). Inextricably linked with Henson’s gifts as a puppeteer were those of the pasticheur. His two feature-length films not involving the Muppets fed on fantastical, picaresque literary sources: The Dark Crystal on Tolkien, Labyrinth on Lewis Carroll. (The fact that the latter also represented the indisputable nadir in the career of David Bowie is, for the purposes of this review, neither here nor there.) In the film Dreamchild, the cinematic meditation on the life of the real Alice directed by Gavin Millar and scripted by Dennis Potter, Henson was the obvious choice to supply the puppets for the sequences set in Wonderland. Later, Henson realised his longstanding ambition to present a series of Greek myths in puppet form. Robert Graves might not have approved, but if it hadn’t been for Henson, audiences in Japan would never have heard of the Minotaur or the Gorgon.

Long after the Muppets have been quietly forgotten, Henson will be remembered and thanked for Sesame Street, beyond doubt the most successful educational television programme ever made. It was launched in 1969 to teach the joys of literacy and numeracy to deprived children in the American inner cities. Under Henson’s supervision, a series of ostensibly ridiculous puppets – Big Bird, Ernie, Bert, the Count von Count, Sherlock Hemlock, the Cookie Monster – were created to star in a show that used the snappy grammar of television advertising to sell learning. In a brilliant parody of the absurdity of sponsorship, each show was sponsored by letters and numbers. ‘This episode of Sesame Street is brought to you by the letters X and Z and by the number 3.’ Sesame Street, like Woodstock and man’s landing on the Moon, is 25 years old. Arguably, its influence runs deeper than either.

The central puppeteering partnership in Sesame Street was between Henson, who performed the grouchy character of Bert, and Frank Oz, who took on his carefree sidekick Ernie. Although Kermit already existed and had been performing on network television since the early Sixties, crucially he was not yet a frog. His feet were not flippered and he hadn’t been given his frog collar. By the time he hosted the inaugural Muppet extravaganza (entitled, simply, The Muppet Show: Sex and Violence) Henson’s alter ego was fully amphibian and in shape for the biologically improbable liaison with the Oz-operated Miss Piggy that propelled the Muppets to movie stardom.

What is often forgotten about the five series of the The Muppet Show is that, for all Henson’s twenty years of success in local and network American television, he had to come to England to get it made. The Muppets may have ended up in Hollywood, but they started out in Borehamwood. The show was financed by Lew Grade of ATV, and as the guest stars were mostly American they had to fly over for a pittance for the privilege of being abused by Statler and Waldorf – the heckling pensioners in the theatre box who never knowingly applauded – or befriended by Gonzo, a beaked creature of preternatural ugliness. Into its day-glo format and piecemeal lay-out this book packs a good deal of information on puppeteers and the technical and technological advances in the art of puppetry, but it refuses to answer the burning question. Exactly what was in it for people like Johnny Cash or Buddy Rich or Deborah Harry? Presumably some of them were using the Muppets to rescue careers in freefall, but in a lot of cases the Muppets must have been using the celebrities.

Henson’s pastiching was not confined to reinventing fairy tales. In the days before Spinal Tap, the Electric Mayhem, the impossibly cool Muppet house band, was probably the best parody of a hard-living, hard-working rock group. In the hilarious calendars that were marketed at the height of the Muppets’ fame, the frame of reference is impressive: Miss Piggy as Fay Wray in King Kong, Miss Piggy as the Forces’ sweetheart and, brilliantly, Miss Piggy as Annie Hall, with Kermit as Woody. The calendar idea led to books, including Miss Piggy’s Art Masterpieces from the Kermitage Collection, in which Miss Piggy modelled for reinterpretations both of the Old Masters and the Moderns: Degas’s The La Danseur, Vermeer’s Young Lady Adorning Herself with Pearls (And Why Not?), Toulouse-Lautrec’s La Belle Epigue and Botticelli’s The Birth of You Know Who. A personal favourite is Jan Van Eyck’s The Marriage of Froggo Amphibini and Giopiggi Porculini, an inferior version of which is in the National Gallery. Kermit is probably the only frog to have posed for both a formal Gainsborough portrait and a Bruce Springsteen album cover.

With the arguable exception of The Perfumed Garden and one or two of the larger paint catalogues, this is probably the most colourful book ever published. Why? It doesn’t seem to be exclusively aimed at children. Henson was a bearded man who wore his hair long and was known to wrap it in a headband. A study has yet to be made of the ways in which the creative drug culture of the late Sixties and early Seventies influenced and interleaved with Muppet culture. But we are entitled to ask the question: is Kermit the frog the result of a hallucination? (Someone else can answer it.)

It is difficult to rank the achievement of Henson alongside the other contemporary purveyors of special effects, because puppetry is an essentially cumbersome skill. Steven Spielberg chose to use computer graphics to get his dinosaurs on the move, rather than put himself at the mercy of so much less manoeuvrable three-dimensional models. All you can say for Henson is that the physical parameters which hampered him when he started in the Fifties had been pushed back by the time of his death, largely thanks to his own efforts. He even got Kermit to ride a bicycle. The frog-as-prince would be green with envy at that, too.

Send Letters To:

The Editor

London Review of Books,

28 Little Russell Street

London, WC1A 2HN

letters@lrb.co.uk

Please include name, address, and a telephone number.