The earlier plays of David Mamet seemed to spring from a meeting between Arthur Miller and Harold Pinter, as if the characters from The Caretaker or The Homecoming had caught the American anxieties of Death of a Salesman. Pinter is also never far from the later plays, and he directed Oleanna in London; but other, more oblique influences now hover in the air. Gregory Mosher, the director of The Cryptogram, thinks Oleanna was ‘Shavian’, and the new play has undercurrents of Chekhov, even Ibsen. At the end, as in The Wild Duck, a child takes off to an attic to die, the victim of the games adults don’t quite know how to play.

Well, we don’t know that the child dies. He just mounts the stairs with a heavy knife in his hands, ostensibly to cut some twine on a box containing a blanket he wants. He can’t die, since that’s where the play ends. He’ll always mount the stairs with the knife, for as long as the play runs and as often as it’s performed. But the play is heavy with danger to him; from the very beginning, it’s hard to think of the child as safe. The knife is like Chekhov’s shotgun on the wall, which has to go off some time. We just don’t hear it going off. This is the 20th century, and Pinter has been here.

The Cryptogram knows where it’s going, but seems uncertain about the road or the reasons. It’s hard to tell whether this is an effect of the writing or of the production. Like Oleanna, it’s a short play in three scenes, with a small cast: three this time instead of two. It’s full of silences and absences, haunted by the unspoken, which is quite an achievement for such a talky writer. Here, as in the essays collected in A Whore’s Profession, Mamet knows when to leave stories alone, how to tell just enough to let them unfurl in our minds. A play, he says in his notes on The Cherry Orchard, ‘speaks to our subconscious’, or should do. The Cherry Orchard is not about trees: ‘Nobody in the play gives a damn about the cherry orchard.’ This makes Chekhov sound like Hitchcock, a man with a McGuffin, and can’t be right; but it does point to the indirection and silence of a play where people talk a lot, and it does suggest buried or implicit connections between the action of a play and the worries of its characters, and between those worries and what the audience is going to pick up, consciously or not. The Cryptogram is also full of what have become Mamet mannerisms: overlapping dialogue, characters constantly repeating the last phrase that was spoken to them. In this mode they recall not Ibsen and Chekhov but Henry James, who could create a riddle out of any old banality: ‘Well, I see everyone at my place.’ ‘Everyone?’ The trouble with such instant creation of depths is that the whole world looks shallow after a while.

Is The Cryptogram shallow? It’s uncertain. Eddie Izzard is Del, a friend of the family, meant to be gay, I think, although only his description of himself as an old queen living in a hotel anchors this idea, and we don’t hear that until pretty late in the play. The family is a mother and a son and an absent father: a permanently absent father, we learn at the end of the first scene, where everyone has been waiting for him, and we now discover he’s leaving his wife and son for good. Lindsey Duncan is Donny, the mother, a role she plays with frazzled charm and confident understatement, and the boy, John, aged about twelve, is Danny Worters, whose age is not in the programme, but who manages to sound like a worried prodigy without sounding like a pain. Izzard is a bit lost between these two, trying to be laid-back but only managing to seem out of it, and since his part is so important, the one that is most clearly written, the play has a hollow space where it seems as if its main meanings ought to be. In the second scene, we find out that Del knew about the father/husband’s infidelity, indeed colluded in it, by lending the chap his room, and Donny throws him out; and in the third, the betraying friend returns, to make propitiation and to deliver a few stagey thoughts about general human rottenness. Donny loses all control, associates her son with all the men who ever betrayed her, and the boy takes the knife and climbs the stairs. Something goes wrong here, as it does in Oleanna. Men are creeps, the story seems to say, and women are victims, harassed or abandoned. But when women get organised, or get angry, they become tyrants or termagants, which, as everyone knows, is far worse than being a creep. In fact, to be a creep is to be only human, a sort of triumph against dogma. Liberalism: the right of all creeps to call everyone else politically correct.

What’s the cyptogram, what’s coded or ciphered? It’s what happened to this marriage, this friendship, where the past went. It’s what happens now and what happened then. The boy insists that he has just torn a blanket that his mother says was torn years ago. The mother must be right, but then why does the boy think he tore the blanket? He’s not lying: he remembers the tear that didn’t happen. But the chief cryptogram is the boy’s fear of sleep. He’s excited, Del says, it’s natural, he’s waiting for his father, he doesn’t want to go to bed. No, Donny says, he’s always like this. And as the play proceeds, this alarmingly articulate boy becomes clearer and clearer about his terrors. He knows he ought to go to bed, he does go to bed; but he can’t sleep, he’s afraid of the voices that talk to him in his sleep, he doesn’t know what they are or why they’re there or why they won’t stop. Perhaps the voices are the turbulence of his parents’ ending relationship, but it’s possible they are something more interior, more intimately connected with the boy’s own fears of the world he is growing into. Or the voices are generated by his parents’ relation to him, the mother’s distraction and the father’s absence. But finally the fear of sleep is more important than what happens in that sleep, becomes a figure for fear itself: to be endlessly awake, never to sleep, a life sentence. Bob Crowley’s set enhances this feeling by giving us a long stair to look at. Behind transparent walls we glimpse John’s bedroom, and a further stair leading to the attic. But mainly we see this stair, almost another character, a wooden haunting, the slanting entry into the world of bad dreams.

A Whore’s Profession collects four previously published books: Writing in Restaurants (1986); Some Freaks (1989); On Directing Film (1991); The Cabin (1992). Mamet doesn’t really believe the theatre is a whore’s profession. He’s a nice Jewish boy, as he tells us. He doesn’t even believe whores are whores: the title is meant to suggest that what looks like a disreputable trade really is a profession, a craft rather than a vice. He quotes a Chicago saying, ‘it isn’t the men, it’s the stairs,’ which seems somehow different when a man quotes it. He tells the story of Mrs Patrick Campbell looking at a couple embracing, and turning to a streetwalker to say: ‘Another great profession ruined by Amateurs.’

The amateurs in film, according to Mamet, are the so-called professionals, the producers and writers and directors who haven’t read their Eisenstein and think movies are about character, and following actors around with a camera, and who can’t read movie scripts unless they are puffed out like bad novels, full of what Mamet calls ‘information’, ‘this dreadful plotting narration that comprises almost all American filmscripts’. ‘Most movie scripts were written for an audience of studio executives. Studio executives do not know how to read movie scripts. Not one of them. Not one of them knows how to read a movie script. A movie script should be a juxtaposition of uninflected shots that tell the story.’ This assertion comes from On Directing Film, which mainly comprises the transcript of a class Mamet taught at Columbia University in 1987.

MAMET’s name, incidentally, appears emphatically in the dialogue while the students are all nameless, compacted into a single generic STUDENT – maybe it’s billing that sorts out the professionals from the amateurs. It’s interesting, too, that the author of Oleanna should casually say, by way of metaphor: ‘in your imagination you can always go home with the prettiest girl at the party.’ What if you are the prettiest girl at the party? You can always go home with David Mamet. Mamet’s sense of film is that its narrative life has to be in the cut not in the shot. The shot is to be what he calls ‘a little photo essay, a little documentary’; the fact turns into fiction, into story, through the way the shots are put together. This is persuasive, and Mamet has behind him his experience as the writer of The Verdict and The Untouchables and, less cogent, his experience as the director of House of Games and Things Change. Knowing your Eisenstein, and thinking about it as Mamet has, means you give good advice; not that your own advice always works for you, even when you manage to take it. Mamet himself says he was ‘the most dangerous thing around’ when he taught the class, a person who had ‘progressed beyond the neophyte stage but was not experienced enough to realise the extent of my ignorance’.

What the Columbia class suggests, however, indeed what most of the writing in A Whore’s Profession suggests, is not that Mamet needs to mend his ignorance but that he is drawn to the analysis of whatever knowledge he’s got. He is a lapsed Talmudist, as he says; he tells his students about Aristotle, Occam, Trollope, Bettelheim; he likes to turn his experience, any experience, into maxims. ‘“Is God dead?” and “Why are there no real movies any more?” are pretty much the same question.’ Really? This is a little too snappy, like the thought about Chekhov and the cherry orchard. But it’s not empty, and it’s useful to think that the second question, like the first, is about the failure of a myth rather than a historical loss – that the very idea of historical loss is often a masked form of myth. And in the plays, particularly American Buffalo and Glengarry Glen Ross, Mamet gets a lot of comic action out of this appetite for maxims, lending it to implausible characters, people whose authority as sages is not only slender but risible. Like Richard Roma, in the second of those two works, all weary sententiousness, half-baked philosophy:

What is our life; it’s looking forward or it’s looking back. And that’s our life. That’s it. Where is the moment? And what is it that we’re afraid of? Loss. What else? The bank closes. We get sick, my wife died on a plane, the stock market collapsed ... the house burnt down ... what of these happen ...? None of ’em. We worry anyway. What does this mean? ... All it is, it’s a carnival. What’s special ... what draws us ...? We’re all different. We’re not the same. We’re not the same ... Hmmm ... It’s been a long day. What are you drinking?

This kind of thing can be a little tiring when it’s done straight, and at length, and in his critical notes and autobiographical essays Mamet certainly tries too hard for the wise and pithy effect. He’s always interesting, but he’s also busy being smart, and he’s hooked on the myth of the American writer as picaresque hero, the man whose life before success was all odd jobs and intimacy with the down and outs. That’s why The Cabin is probably the most effective piece of writing in this volume. It has a raw edge to it, as if the material is a little too rough for even Mamet to turn into adages. We hear about his family, about the way his sister was beaten; about his own lonely, happy days as a newly successful writer. And we get this story, which Mamet describes as an ‘improbable exchange’; a sort of cryptogram, a lie which exposes itself and then seems to be something more, or something other, than a lie:

I had broken a strap on my leather shoulder bag, and went into the shoe-repair store to have it fixed. The owner examined the bag at length, and shrugged. ‘How much to fix it?’ I said.

‘That’s gonna cost you twenty dollars,’ he said.

‘Twenty dollars? I said. ‘Just to fix one strap ...?’

‘Well I can’t get to it,’ he said. ‘I can’t reach it with the machine, I got to take the bag apart, do it by hand, take one man two, three hours, do that job.’

So I sighed. ‘Oh, all right,’ I said. ‘When can I come back for it? Thursday? Friday?’

‘Naaah,’ he said. ‘Go get a cup of coffee – come back ten, fifteen minutes.’

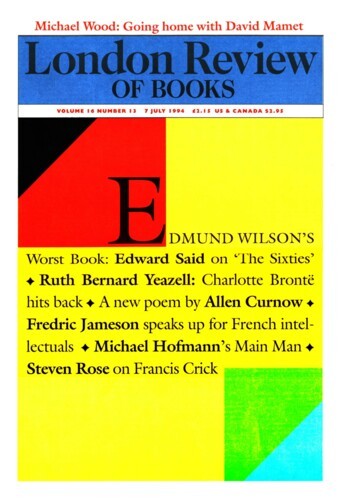

Send Letters To:

The Editor

London Review of Books,

28 Little Russell Street

London, WC1A 2HN

letters@lrb.co.uk

Please include name, address, and a telephone number.