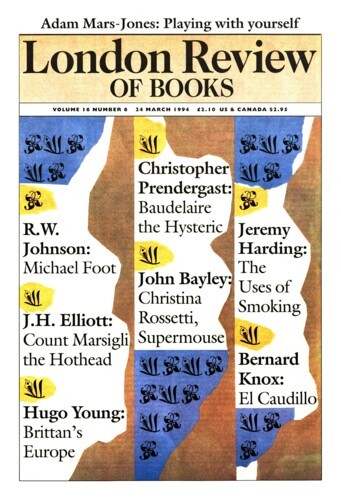

At the Party Conference following Labour’s crippling defeat in the 1983 election Michael Foot stood before the massed ranks of the faithful to account for his stewardship of the Party. ‘I am deeply ashamed,’ he began. Unfortunately for Mervyn Jones, who both loves and admires his subject and would have us dwell on other things, it is the freeze-frame of that moment which lives on. For Foot had led Labour to its worst defeat since 1922, a defeat so bad that it handicaps Labour still. In almost exactly half the country’s constituencies the SDP-Liberal Alliance ran ahead of Labour. Eleven years later, despite the implosion of the Alliance and two better elections for Labour, the Liberals have clung onto the majority of those bridgeheads: for Labour to win a Parliamentary majority of any comfort now it has to perform the difficult trick of going from third to first place in a considerable number of seats. This ‘Foot deficit’ may well live on to haunt Labour leaders into the next century, and with it will go the memory of Foot as the most disastrous Labour leader since Ramsay MacDonald.

All of which is a considerable pity, for Foot is undoubtedly one of the nicest and most decent men to sit in Parliament. The trouble perhaps – or part of it – is that it has always been rather too easy for him to mistake myth for reality. His father, the remarkable Isaac Foot, was the very model of the battling West Country Liberal, a man of wide learning who amassed one of the finest private libraries in the country. Born the fifth child of seven, the young Michael grew up among a veritable forest of Foots, all passionately committed to the Liberal verities in a household where a radical Whig sense of history, literature and rhetoric was not just part of the furniture but pretty much what life was for. Most of Foot’s household gods were to remain the same all his life – Hampden, Swift, Hazlitt, Cobden, Bright, Mill, Gladstone, Wilberforce and Charles James Fox. There was, in time, one great socialist addition to the pantheon, Aneurin Bevan. It followed that politics was mainly about two things: standing up for moral principle and making wonderful speeches. Any idea that it was also about perks and patronage and necessary trade-offs, about the brokering of compromises between material interests and pressure groups, about spoils and contracts, about pork-barrel and pay-offs – all this was foreign to the Foot world.

In an earlier generation Foot would probably have been a Nonconformist lay preacher. In this secular age, however, the peculiarity of such Nonconformist radicals is that they find they can manage without God, but continue to rely heavily on the Devil. While the ‘struggle for socialism’ always remained somewhat vague and woozy, the obligation to stand against this, that or the other evil was always absolute. Indeed, Foot’s political life consisted largely in identifying such evils so that one could stand against them: Fascism, Appeasement, German re-armament, apartheid, colonialism, the Bomb, unemployment and so on. In this he has, of course, been typical of the Labour mainstream. So dominant did this modus operandi become that no one seems to have noticed that without a sense of the Christian goal/socialist heaven such thinking is intrinsically oppositional. Not only is it happier in opposition than in power, but it tends to the view that power and the holding of it are intrinsically bad things: Acton’s aphorism about all power corrupting touches a deep nerve. Not surprisingly, people who feel like this hardly know what to do with power when they get it; and there have been quite a few Labour ministers who managed to remain psychologically in opposition through quite long periods in government.

Foot, until the end of his career, exemplified many of these traits. His rhetoric is instinctively religious even though he is no churchman. The right thing to do was to ‘preach socialism’. He would rail against the Bomb as ‘a crime of such monstrous proportions that it is impossible to find a language with which to describe it’, as an ‘absolute evil’ which it must be right to resist, whatever the political fallout. Faced with the fact that unilateralism cost votes, he would insist that he had to fight the good fight ‘because it is right’. As a young man, he would speak in praise of those who, following in Bevan’s path, would go about ‘fighting for socialism’, ‘striking a blow for socialism’ and so on, in the same spirit as a missionary applauding young ordinands who take the Gospel among the heathen. In this tradition rhetoric is no mere speechifying but the properly cadenced and dignified bearing of the Word. When someone spoke passionately and well, they would be congratulated on the number of ‘converts for socialism’ they would win by such bravura performances, for it was assumed that conversion to socialism was an experience akin to being saved, achieved through the inspired oratory of an apostle, whether a Billy Graham or an Aneurin Bevan. Such spirituality found the material world quite repulsive. Thus Foot objected to the EEC because it would mean joining ‘the rich nations’ club’. And, of course, it would diminish the House of Commons, an unthinkable desecration: the Commons was a sort of cathedral in that rhetorical tradition. Similarly, he denounced Attlee and Bevin for subscribing, as Jones puts it, ‘to the Tory belief that British national interests, not ideological sympathies, should he the mainspring of foreign policy’.

At Oxford Foot (then still a Liberal) was, predictably, President of the Union but took only a second in PPE, never actually getting the hang of either philosophy or economics. After a brief spell working for the Blue Funnel shipping line (where he loathed his employer because of his ‘career of sordid and unrelieved money-making’), he gravitated to Kingsley Martin’s New Statesman, but Martin let him go after a while. ‘He’s a good fellow and not a bad journalist, but not A plus,’ Martin remarked, the problem being that, though fluent, Foot was too didactic. Embarked on a career as socialist pamphleteer and propagandist (he had stood for Labour at Monmouth in 1935), he moved on to Tribune, then in full flood of the passions unleashed by the Spanish Civil War, the rise of Fascism and the tangled politics of the Popular Front. Foot was in his element. But Victor Gollancz insisted on the sacking of the paper’s editor, William Mellor, who had quietly refused to toe the CP line over the Popular Front. Foot was then offered the editorship, an interesting assessment of his malleability, given that he shared Mellor’s views. The Party had effectively decided to take over Tribune but, unwilling to risk appointing a declared Communist as editor, thought Foot would be more manipulable than Mellor. Foot nobly refused to be more than acting editor and H.J. Hartshorn, a secret party member, was appointed in his place.

Foot moved on, recommended by Bevan to the Evening Standard where, famously, he became a protégé of Beaverbrook for whom, like his great friend A.J.P. Taylor, he was to have an abiding affection. The Standard then was no mere rag: Foot was to recruit Jon Kimche, Arthur Koestler and Isaac Deutscher to write for it, and it provided Foot with a secure and happy base. Over the years Beaverbrook showered him with gifts, right-wing opinions, money, and a friendship which, given their opposed views, did both men credit. But Beaverbrook did not want his journalists writing independently of his papers so when Foot, Frank Owen and Peter Howard decided, in the wake of Dunkirk, to write an instant book denouncing the Fascist sympathisers and appeasers who had brought things to this pass, it had to be done anonymously. The result, Guilty Men, though written in just four days, was to be the most successful of Foot’s books despite the refusal of W.H. Smith’s to stock it. It does not now read well; there is some deeply bogus scene-setting by Foot, whose asthma had made it impossible for him to see the action he so colourfully imagined, and much of it is mere ranting. For all that, it worked and while one might add a few critical words about those on the left who opposed re-armament, Foot’s targets seem just as guilty now.

One has much the same feeling watching Foot progress through his years as an MP after 1945. Some of his judgments were, to put it mildly, questionable. ‘American capitalism ... is the most evil force in the world today’ seems an odd thing to say in 1946 when Koestler had left Foot in no doubt about the reality of Stalin’s USSR. But on the whole Foot was far more often right than most. He warned Bevan endlessly that it would be impossible to prevent the Israeli state coming into being and folly to try. His opposition to America’s Cold War policy never led him into the fellow-travelling of a number of Labour MPs, yet he took an equal distance from Cold War anticommunism. His attacks on British colonialism read well today, as do his later speeches on Rhodesia and Vietnam. Even his Bevanite partisanship had its points: the whole quarrel began, after all, with Gaitskell’s insistence that Health Service charges were necessary to pay for the increase in the defence budget to £1.25 billion. Yet when the Tories won the 1951 election, Churchill announced that it was quite impossible to spend that much on defence that year, causing Gaitskell to retreat in some disorder, claiming he had only been using ‘round figures’.

Overall, however, Foot’s Bevanism was a waste of his best years. Indeed, the long-drawn-out feud within the Party over what it might hypothetically do were it to gain power now seems quite incomprehensibly silly, for the feud itself made the prospect of power remote. It is also hard not to feel that Foot’s idolatry of Bevan was somewhat soft-headed. Bevan was, after all, a childish, petulant, self-centred man, far too convinced of his own charm and persuasiveness. In the end he quite royally let his own followers down while always expecting them to do his will. When Tribune had the nerve to criticise him, his wife, Jennie Lee, tried to have the paper closed. In fact, the whole period now seems shrouded in sectarian madness, right down to Jennie Lee claiming that her husband had been murdered by the stress he was put under by his critics. One has the feeling that Foot could not be his own man or achieve anything worthwhile until Bevan was, mercifully, dead.

Wilson at first left Foot out of his government in 1964 and by the time he relented, Rhodesia and Vietnam made Foot happier to stay out. Accordingly, it was only in 1970, at the age of 57, that Foot entered the Shadow Cabinet and only in the years between 1974 and 1979 that he held government office. It was not a happy period: at last he had made his peace with political reality, but his judgment remained far too soft and he was easily pushed around by the unions. The sight of Foot arguing that it was right to sack workers because they had refused to join their closed-shop union made libertarians blench. Christopher Hitchens was not alone in ridiculing him: ‘Pay policy, government secrecy, expenditure cuts – you name it and Foot will find a windy justification for it.’ Worst of all, Foot toured India and gave strong public support to Mrs Gandhi’s emergency measures, despite the widespread detentions without trial, the frightful campaigns of compulsory sterilisation, and so on. Again, he did it because Mrs Gandhi was his friend and, as with Bevan, friendship blinded him to the facts in front of his nose.

Finally, there came the two and a half sad years of party leadership. Foot seems to have been pushed into this disastrous venture partly by a consciousness of Benn, his rival for the leadership of the Left, coming up on the track behind him, partly because the man he wanted to back, Peter Shore, seemed unlikely to beat Healey, and partly because of the urgings of those who felt he was the only man who could avert a damaging party split. Jones is keen to convince us that only Foot’s leadership ‘averted catastrophe’ for Labour, and it is certainly true that a Healey leadership would have sparked a major left-wing revolt in 1980. But under Foot there was a major party split anyway, and by 1982 it was perfectly clear that Labour could never win with him as leader. He was nearly seventy, walked with a stick, was blind in one eye, had to have documents read to him and was a disaster on television. He was ignorant of and sometimes hostile to the arts of modern politics, uncaring of ‘image’ dismissive of polls and unaware of how electioneering now worked: with every poll showing Labour’s weakest suit to be defence, the one subject he had to avoid like sin was defence – instead he insisted on speaking about it.

The real question about Foot’s leadership is whether he shouldn’t have ceded place to Denis Healey a few months before the 1983 election. The polls suggest this would have produced a dead heat with the Tories as Alliance voters defected back to Labour en masse. Here Jones is far too kind and tries to throw the blame on the Shadow Cabinet for not coming forward to suggest such a move. But this is absurd – and in any case Gerald Kaufmann, desperately aware of the disaster to come, did make such a démarche. Jones also manages to avoid almost all mention of Labour’s 1983 election manifesto, ‘the longest suicide note in history’, and Foot’s clear culpability in allowing such a crazy document to see the light of day. He is also by a long way too kind about Jill Foot’s appalling misjudgment in encouraging her husband to fight on, thus guaranteeing his personal and political humiliation, and then suggesting, in mid-campaign that he was soon to retire anyway. Finally Foot compounded the damage by self-indulgently helping to secure the succession for another hopeless loser, Neil Kinnock. We have had sightings of the young Kinnock on and off throughout the book, first as an expert heckler at Tory meetings in Ebbw Vale, later letting out ‘a blood-curdling Indian war-whoop’ as Foot wins the leadership: one’s heart sinks at the thought of the boyo to come. At one stage the Shadow Cabinet vetoed Foot’s attempt to make Kinnock the front-bench spokesman on employment, a comprehensive vote of no confidence of which Foot took no notice: Kinnock, after all, went about preaching socialism and winning converts in just the way Foot approved of.

When Wilson and Callaghan left the premiership they were both thoroughly disenchanted with the Labour Party and were not above making things a little harder for their successors, even in the middle of an election campaign. The opposite is true of Michael Foot: he genuinely loved and believed in the Labour Party, and yet he did it even greater damage. The fact is that at a personal level political leadership has to be about the power to achieve things, the wanting of that power sufficiently to give structure to a career, and an understanding and ease in handling it, with all the compromises that involves. Michael Foot didn’t much want to live in that world, which is why he only finally shuffled into it in 1974 – 39 years after first running as a Labour candidate. It is also why he didn’t make much of a fist of it then: the endless tub-thumping and pamphleteering of an opposition tribune do not provide the necessary training.

Send Letters To:

The Editor

London Review of Books,

28 Little Russell Street

London, WC1A 2HN

letters@lrb.co.uk

Please include name, address, and a telephone number.