The high noon of imperial expansion towards the end of the 19th century produced an archetypal tale. Kipling’s version of it is ‘The Man Who Would Be King’, which like all Kipling’s early tales made a great impression on Jack London. His own version, ‘An Odyssey of the North’, concerns an Aleutian Indian whose betrothed is stolen from him by a Norwegian seal poacher, a giant with a golden mane and the blood of the Vikings, much the same as the hero of Kipling’s story, and also of Rider Haggard’s romances. Together with his faithful friend, the tale-teller and survivor, Kipling’s hero founds a fabulous kingdom in the wilds beyond Afghanistan, and meets his fate when his wish for a wife from among his native subjects makes them realise he is no god but a man, whereupon they kill him.

Both tales are filled with ideas about blood, confidence and power, the sovereignty of race and the conviction of manifest superiorities. Both are founded on imperial superbia and the hubris it brings; it is the very conviction of his superiority that brings the hero his final come-uppance. Both, like all archetypal tales, are full of prophecy and ancient wisdom, oddly mixed with romantic nonsense, and with the vulgar conventions and ideas of their own limited period. And both have undoubted potency, for London is as effective a myth-maker as Kipling. He reverses the Kipling plot, while exploiting Kipling’s casual expertise with names and knowhow and local lore, and his inspired use of a quasi-biblical jargon. His Indian hero works his way through the whole of what we should now call the Pacific rim, from the Bering Sea to California, in search of the man who has stolen his betrothed. When he finally catches up with him in the Klondike snows they have found together a fabulous and undiscovered goldmine. But cold and hunger are killing them, though the cunning Indian has survived by stealing and concealing food, in order to obtain his revenge.

The Northman’s wife, for so she has of course respectably become, has also become so civilised that she does not recognise her former betrothed. As her husband dies, the Indian reveals himself to them both and claims his bride, sure that she will wish to return with him to ‘the yellow beach of Akatan’. But she attempts to knife him, and dies in the snow with her dead, white ascendancy husband in her arms. Racial superiority has had its way, but has also been defeated. After incredible hardship the Indian gets back to a settlement, and tells his tale to Prince and the Malemute Kid, two buddies of the far North whom we encounter in several of London’s stories about that last outpost of both romance and epic (the tale was written in the late 1890s). This aspect of the matter is fallen back on, for both style and subject, in the less good tales; and, as is usual with London, there is often an odd sexual ambiguity at the heart of cliché itself. Kipling has similar ambiguities, but they do not affect the pungency and precision of the writing. It is only fair to emphasise that London had to keep his eye firmly fixed on the readers of the magazines he wrote for, in a way that had never bothered the more obsessed and manic genius of Kipling.

And so London’s strong men say to their girlfriends, or rather they ‘passionately cry’: ‘Even unto death I shall claim you, and no mortal man shall come between.’

And a handsome fellow he was as he waded among the fierce brutes ... dragging them over and under the frozen traces till the team stood clear. Nipped by the intense cold to a tender pink, his smooth-shaven face told a plain tale of strength and indomitability. His hair, falling about his shoulders in thick masses of silky brown, was probably more responsible for winning the woman’s affections than all the rest of him put together. Yet when men ran their eyes up and down his six foot two of brawn, they declared him a man, from his beaded moccasins to the crown of his wolfskin cap. But then, they were men.

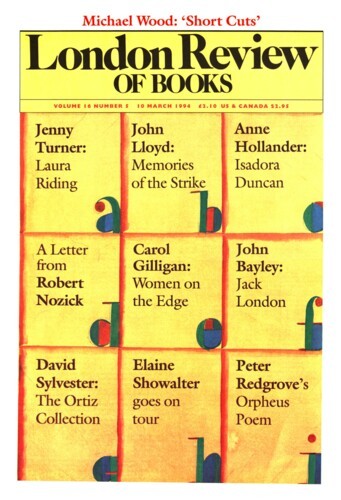

No doubt they were; but tender pink faces are by no means limited in the Frozen North to lady visitors, who usually come either in the form of faithful squaws or broken blossoms. Although ‘Even Unto Death’ is one of London’s feeblest stories, it demonstrates the odd and winning openness of his literary persona: he is never at all shy about his sympathy with femininity in men, and his understanding of its attractions. The many photographs in this handsomely produced collection show his own decidedly feminine or boyish features, and the deeply innocent and confident look of pristine California. Only 40 when he died of drinking, working, playing and the sheer ebullience of success, London remained all his life the self-made undergraduate, working his way through the college of manly experience and always ready for further deeds of initiation. His personality is far more sympathetic than Hemingway’s, though he has none of Hemingway’s unerring originality as a stylist; and this is partly because of the cheerful openness of his sexual ambiguities. It is perhaps a function of style in Hemingway, as in Melville, to mask such equivocations in a way that London’s more artless manner is incapable of doing.

As he said himself, he was no good at plots, or ‘Origination’ as he called it; but his editors rightly point out the immense scenic variety of the two hundred short stories he produced in a 23-year career, listing it alphabetically for convenience. ‘Ageing, alcoholism, boxing, bullfighting, child labour, ecology, extraterrestrial fantasy, gambling, goldmining, hoboing, love (primitive and atavistic as well as romantic and ideal)’ and so on to ‘seafaring, slumdwelling and socialism’. Towards the end of his writing career he discovered Jung, and wrote a good number of fantasies about the anima. London, however, never took himself wholly seriously: there is something almost Pushkinesque about the lightheartedness with which he mixes the short-story genres together, so that each makes a certain amount of sly fun of the other. What he lacks in the master touch he can make up in sheer exuberance, as in a late story called ‘The Princess’, in which three hoboes tell tall tales of the exotic and wonderful woman they once encountered in distant parts – the animae of their wanderings.

The editors are certainly justified in claiming that London’s art – technique might be the better word – was still developing when he died. Academicism can never resist claiming a son of nature for its own, however; and it is its own kind of hindsight which makes the claim that as London wrote he began ‘to firmly grasp the principle of the Jamesian “central intelligence”, as well as the principle that T.S. Eliot would later popularise as the “objective correlative”’. It is quite true that London clearly had the greatest respect for not only literary craft but for the kind of critical principles that were taught at the universities he sporadically attended and even lectured at. He never affected any degree of philistinism, as his successors were to do, but was as much in love with learning as he was with life: in that respect very much an American of his time. Captain Larsen of his novel The Sea-Wolf is unconvincing as a demonic figure, but as an autodidact like his creator he makes a great deal of sense. In some ways London was not so unlike an American version of Thomas Hardy.

They certainly shared the same feeling for fact. The editor of Cosmopolitan, paying London $750 a story in 1910 – a serious sum in those days – stipulated that they should be ‘virile, throbbing with reality, but not likely to repel with too gross an expression or too brutal a realism’. London obliged after his fashion, though the editors go a little far in their enthusiasm when they claim for one rather indifferent and pretentious tale, ‘The Night-Born’, that it is inspired structurally by Conrad and thematically by Thoreau, and that ‘it dichotomises the symbolic values of male/city versus female/nature’, also dramatising ‘the dynamic process of spiritual self-fulfilment that Jung would later describe as “individuation”’. In fact the simplicity of the stories is what counts: and it is not simplicity of the intensely self-conscious kind which Hemingway was to perfect, and which is found in contemporary short-story writers like Raymond Carver, but a kind of solid interest in what happens next after one thing has happened.

A traveller in the Frozen North has one or two bits of bad luck: socks and matches getting wet, things of that sort. They produce a deadly escalation which eventually leaves him quietly dying of cold in the snow, with no greater sense of fear or importance than he had at the beginning. The really significant thing about the best stories is precisely their lack of revelation or epiphany – the things which no practitioner of the genre can afford to be unconscious of today. This sort of story would lay heavy emphasis on the lack of significance in its own narration: an intentionality of anticlimax. London certainly realised what a good theme he had got hold of, for he wrote ‘To Build a Fire’ twice, in two versions, in the first of which the man survives and in the second he doesn’t. The difference is simply one of sequential chances: will he get the matches to light before frostbite makes his hands incapable, and so forth – and the reader follows the sequence spellbound. How it ends hardly matters. The first version is to my mind the best, because the most ordinary. Since the man may survive or may not, which he does makes no difference to the story. (A modern narratology expert would shake his head at that.) The frostbite vs match sequence is more detailed and graphic in the first version, and two homely bits of wisdom are proffered. ‘Travel with wet socks down to twenty below zero; after that build a fire.’ The second, which ends the tale, is simpler. ‘Never travel alone’ is the precept of the North which the survivor will remember. London was right not to call the story ‘Wet Socks’, the title which would tempt a short-story writer today.

Kipling’s sense of fact is by contrast always suspect. One of his best stories, ‘On Greenhow Hill’, ends with a rifleshot, and a deserter bowled over at four hundred yards. Unfortunately we do not believe in that rifleshot: it has been too carefully led up to and expertised. London’s sense of fact, like Hardy’s, is much more humdrum; and this serves him in good stead in all the exotic places he set the stories, whether the Klondike or Melanesia; and as the editors rightly point out, London was the first writer to be totally naturalistic about the South Seas – no Treasure Island stuff. Digging for gold on the banks of the Sacramento becomes just another tedious and dangerous job; and he must be the only writer to describe with complete fidelity just how a bucket line over a river gorge really works. To return to the resemblance between ‘The Man Who Would Be King’ and ‘An Odyssey of the North’, the basic difference between the two stories is that one took place and one did not. That is to say the events in London are true: those in Kipling are made up. Kipling brilliantly builds this into his tale by suggesting at its end that it never happened. Jack London would not have done that.

Send Letters To:

The Editor

London Review of Books,

28 Little Russell Street

London, WC1A 2HN

letters@lrb.co.uk

Please include name, address, and a telephone number.