In Neil Jordan’s film The Crying Game, a renegade IRA man ends up in the arms of a male cross-dresser. It is a typical Post-Modern drift – from politics to perversity, revolution to transgression, the transformation of society to the reinvention of the self. Revolutions are made in the name of wealth, freedom, fullness of life; but those who make them are the worst possible image of the world they hope to fashion. Because asceticism, self-sacrifice, ruthless utility are among the essential revolutionary virtues, there will be no place for the founding fathers in a truly transformed state. Indeed, their redundancy will be an index of its success. There will, however, be a place for the mothers and daughters; for their role, in a certain feminist conception, is to remind us here and now of the sensuous fulfilment their grim-faced menfolk must necessarily defer. If the women practise a utopia of the present, the men must forego that privilege in seeking to create the conditions in which it will become available for everyone. It is an antithesis ripe for deconstruction, if one thinks of the great women revolutionaries; but to relax the tension it outlines is either to lose grip on the values one is fighting for, or to indulge in a purely selfish prefiguring of the political future. That other Irish transgressor, Oscar Wilde, understood that his own indolence dimly portended the New Jerusalem in which nobody else would have to work either: just lounge on the couch all day and be your own communist society. But he had to pay a heavy price for this prolepsis, in guilt and morbid narcissism; and the transgressive heroine of Aisling Foster’s accomplished first novel must also reckon the political cost.

Rita Fitzgerald, scion of a Castle Catholic Dublin family in the years of the Irish war of independence, marries Frank O’Fiaich, Eamon de Valera’s right-hand man, and becomes embroiled in a plot to finance the Irish revolution with the Romanov crown jewels. (Like many a fabular event in Irish history, this one is conceivably true.) The Bolsheviks entrust the jewels to the Irish as security for a loan to float their own political project; Rita ends up as guardian of the loot, stitching it into her underwear and decking herself out with priceless rubies and tiaras in the furtive solitude of her bedroom. These precious stones signify a sumptuous excess which challenges political ascesis; and as the secret place of Rita’s pleasure they memorialise her sexual awakening, in an erotic encounter with the Bolshevik woman who hands them over to her. The prose of that splendidly perverse scene is itself lavish, coruscating, pressing beyond the spare realism of the political narrative; so that the interweaving of styles is a confrontation of masculine realpolitik with feminine utopia, a celebration of prodigality and shameless extravagance over the historically functional. These fairytale gems are a threat both to the zealous austerity of the Irish Free State and to the novel’s own realist plausibility: would Rita really have secreted them for so long under her skirt, and would her fanatically puritan husband really have overlooked her sporting the odd bauble in public?

‘No symbol where none intended,’ a more celebrated Irish author remarked; but Foster’s symbolism is relentless, voulu, calculatedly self-conscious, the place where the text flamboyantly parades itself with all the narcissism of its protagonist. Like Conrad’s Nostromo, with its stolen silver, Safe in the Kitchen makes a deliberate fetish of the plundered booty at its centre – and this both in the Marxist sense of the term, as Rita comes to impute a purposive life to the inanimate, and in the Freudian sense of the fetish as plugging an intolerable gap. That gap is Rita’s dumped, discarded status as the politically sidelined wife of a bigoted Irish patriarch; and her rummaging in the Romanov treasure is thus poverty as well as wealth, a meagre compensation for a sterile existence. The jewels, as chunks of dead matter, symbolise that sterility as well as transcending it; and they thus come to assume something of the lethal ambivalence of Henry James’s Spoils of Poynton, which tread a hair-thin line between aesthetic splendour and aestheticist barrenness. The exotic artifice of Rita’s hoard questions the supposed naturalness of nationhood; but it also embodies a kind of hothouse morbidity. To be the gem in the kitchen is as ambiguous a privilege as being the angel in the house; and as Rita grows steadily more obsessive about her swag, in a way which subduedly parallels the fanaticism of the male politicos, it begins to wreak havoc around her, leaving a trail of violence and deception which encapsulates the degraded condition of post-independence Ireland. If the jewels start out as a symbol of revolutionary idealism, they end up as a dismal index of its decline.

As with James’s golden bowl, then, there is a subtle flaw in these stones which the narrative will gradually prise open. They are, after all, the fruit of Tsarist exploitation, though the story makes significantly little of that. And there is a Jamesian motif, too, in Rita’s early encounter with the Gaelic revival, as a kind of starry-eyed Isabel Archer straying into what will turn out to be a deathly entrapment. In the end, the novel will boldly turn all this around, as Rita refuses to hand over the remnants of her treasure to a cynical Russian politician, and is grudgingly admired by him as maybe ‘the last true revolutionary’. She, it would appear, is now the guardian of that pristine political idealism, in a land of political clientage and corruption. But this would seem no more than a symbolic shuffle. For the truth is that Safe in the Kitchen has hardly a good word to say for anything that happened in Ireland between the Easter Rising of 1916 and the present. In this chillingly negative account, post-colonial Ireland is absolutely nothing but purism, patriarchy and political patronage; this supercilious dogmatism is now something of a conventional piety among Irish middle-class liberals at home and abroad. The novel may end on a note of nostalgia for the high hopes of a long-buried era, but it found precious little to approve in that epoch when it was examining it a few hundred pages earlier. Rita’s husband is an identikit revolutionary zealot, conveniently two-dimensional and unflaggingly repellent. Her reactionary parents are satirised for their high-class distaste for petty-bourgeois radicals, but Rita herself is a rare old snob. Irish republicanism is condemned for sidelining women – a judgment sorely in need of some historical fine-tuning – but it hardly seems worth joining up with in any case. Throughout the novel, the line between a proper feminist critique of Irish nationalism, and a privileged middle-class scorn for it, is notably hard to draw. Those banished to the touchlines are in an excellent position to criticise the game; but they are also likely to have rather a remote view of it.

In the structure of Foster’s novel, the political and the aesthetic interbreed, as the tale of the Tsarist spoils weaves its way into an admirably ambitious narrative of Ireland from independence to the present. In its content, however, pleasure and politics, transgression and totality, come to seem inexorably at odds. The oppositions break apart in the figure of Nina, the Soviet who turns over the jewels and turns on the heroine. Nina is both a feminist and a Bolshevik, combining a materialist contempt for Western decadence with an expert line in sensual gratification. But Nina, significantly enough, is the book’s most painfully cardboard character, a blowsy stage-Russian who has strayed in from some second-rate spy thriller. It is hardly surprising, given the book’s Post-Modernist assurance that the erotic body is one thing and political organisation another, that it should then move to deface Nina when she makes a final appearance, abruptly reducing her to a calloused apparatchik.

It would appear, then, to be a choice between rubies and the republic. The name for this dilemma in Ireland has traditionally been William Yeats, caught on the hop between culture and nationalism, political history and a lonely impulse of delight. That these imperatives cannot easily be reconciled, that men and women will tear down a fine old house if they need its planks for shelter, is indeed a tragic contradiction, as Yeats’s poetry and this excellent novel warily acknowledge. Culture is not worth preserving if it rests on exploitation; but without that culture we will have no image of an emancipated world. Caught alike in this conundrum, the Left habitually opts for political utility, while the Right protects civility from those who seem to threaten it. All that can be asked from each party is that they reckon the cost of their inevitably partial solution.

The strength of Aisling Foster’s novel is that it pays the price for its defence of civility, as the central symbol of that condition comes – perhaps somewhat beyond the book’s intentions – to appear less and less unequivocally positive. But it does not pay the price in the sense of granting its opponents what it can, of estimating what might be valuable in the political realm on which it coldly turns its back. Revolutionary nationalism is uniformly life-denying – a case the liberal may confidently affirm of Twenties Ireland, as she might, less doctrinally, one imagines, of modern-day South Africa.

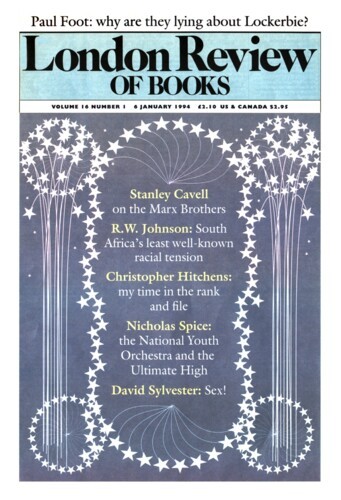

Send Letters To:

The Editor

London Review of Books,

28 Little Russell Street

London, WC1A 2HN

letters@lrb.co.uk

Please include name, address, and a telephone number.