Karl Miller’s decision to resign from the London Review of Books is a sad moment for the magazine which, with Mary-Kay Wilmers and Susannah Clapp, he founded in 1979. In all important respects, the present character of the London Review was established then, in the closing months of 1979 and the first months of 1980, even though it appeared as an insert in the New York Review of Books. I can well remember the experience of reading those early issues, usually at dinner, solitary in some Northern European hotel, on trips as a sales rep trying to flog novels to the Norwegians or poetry to the Finns. The LRB was a wonderful companion, and the impact it made on me was of a new voice in serious journalism pitched subtly between the slightly stuffy intonations of the TLS and the too easy drawl of the New York Review with its tendency to long-windedness unleavened by wit. The voice of the LRB seemed sharper and more quirky, never coming quite from the expected direction.

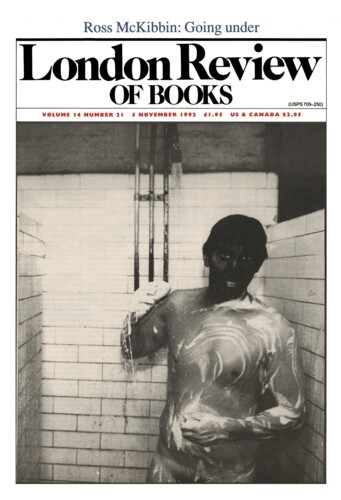

Like the offspring of Dermot Trellis’s eugenic experiments in At Swim-Two-Birds (he had found a way, he believed, to breed old age pensioners eligible for state benefit from day one), the London Review of Books sprang into the world as a fully-fledged adult. The three editors who brought it to birth, and nurtured it through most of its first 13 years, were not new to the game. Karl Miller himself had been literary editor of the Spectator and New Statesman, and, in the late Sixties, helped by Mary-Kay Wilmers and Susannah Clapp, he had edited the Listener. The style of editorship which they brought to the London Review has never been one to declare its intentions loudly or plant its effects too obviously. Indeed, it has reserved its subtlest moments for readers willing and amused to seek them out: in the oblique wit of a title given to an article (‘Least said, soonest Mende’ read the heading for a piece on the anthropology of the famously taciturn Mende tribe); in a cryptic rubric on the front cover (‘Gray’s Elegy, and Wynne Godley’s’ – one of Karl’s recent ones – achieves an almost Japanese inscrutability and aesthetic poise); in the choice of a cover picture (once, for the Christmas Issue, Karl chose the photograph of an old Jew in the Lodz Ghetto peering through a tiny wicket as though on the look-out for his Christian persecutors); or in the educative design of an issue, in which the sequence of articles makes up an elegantly structured whole.

In the course of these 13 years, humour has never been far away from the editorship of the LRB. The paper once published an entire letter about Deconstruction in Japanese, and a review of Wolfgang Hildesheimer’s laborious hoax Marbot was so cleverly tongue-in-cheek that the earnest German author thought it was serious and wrote in to point out the mistake. But the LRB has not been all hermetic innuendo and baroque wit. On political issues, the paper has been straightforward and consistent and passionate. Fiercely opposed to the Falklands and Gulf Wars, unceasing in its criticism of Margaret Thatcher and all her ways, uncompromising in its refusal to accede one jot to the culture of slick presentation and the sound bite, the London Review of Books has contrived to sit squarely across and against the grain of the decade through which mostly it has existed. Karl’s own view of what the LRB is for was succinctly set out in two brief statements of intent, published in the very first issue of the paper, in October 1979, and, a few months later, in the issue which announced that the LRB would be hopping it from the maternal pouch. Then, Karl spoke of a belief in the bearing of politics on literature, and of a desire to link the world of academia and ‘that wider community of informed and interested readers which used to be among this country’s claims to fame’. They are ambitious aims and they explain why the LRB continues to have more the character of a 19th-century paper than a late 20th-century Sunday supplement (Karl was recently compared to Francis Jeffrey, editor of the Edinburgh Review). But if the idea behind the LRB is old-fashioned, it can hardly be thought irrelevant, as the illiteracies of political rhetoric and academic jargon make clear. On the latter Karl was particularly and typically trenchant:

If deconstruction conveys that there is nothing to be done, it also conveys that there is plenty to be said. The second of these two aspects relates to the willingness of the defeated to write books ... Structuralism unites aggression and defeat ... It is a thriving discourse which expects to bewilder: its popularity is that of the designedly unpopular. So, while it is perfectly true that its ideas have travelled further and wider than can generally have been thought likely in the days when they were first identified, it is also true that the general reader does not know about it – that, at the last count, so to speak, only two MPs in the House of Commons had ever heard the name and both of them were Bryan Magee. This doesn’t prove the ideas wrong, or right. But it does indicate that even a small paper has to have more than one readership.

Scepticism, obliqueness of tone, dislike of cant and suspicion of enthusiasm, a dour sense of humour, delight in the unusual bordering at times on the perverse, combativeness of spirit: it may seem fanciful to attribute personality in this way to a magazine which outwardly appears to be just a mixed bag of essays by various hands. But giving character to a magazine is what editing is all about. If the LRB has half the character that seems to be indicated by the loyalties and enmities it has inspired, then this is because it has been edited with skill and passion – because, quite simply, it has been edited with personality.

Karl Miller’s skill, passion and personality have been lavished on the LRB. Perhaps because his own beginnings were far from soft, Karl is fiercely sensitive to social and political injustice, and has a sense of the world as a hard place, and this makes him wary of attitudes and positions which have an air of taking the easy way out. So when words like ‘truth’ and ‘soul’ cropped up in a contributor’s copy, his hackles would rise: not because he’s a cynic, but because he knows what loose talk of these things has led to in the past, and because he regards whatever it is that ‘soul’ and ‘truth’ point to as too important to be so glibly labelled, so easily taken as read.

For Karl, editing is not about strokes of genius, grand visions, stylish gestures, but about the down-to-earth realities of a good piece of prose, about well-structured arguments and exactness of expression. He sees editing as a craft as much as an art, a matter of unflagging attention to detail – to the routine grind and fiddle of sub-editing and proofreading – as well as an opportunity to find an apt and surprising match between author and subject. He is a great editor because he combines both the craft and the art of editing, and is as dedicated to the one as to the other. Editorial flair and a concern for the smallest textual detail have the same root: they both stem from clarity of aim, from knowing precisely what is wanted and how practically to get there. The irritation Karl felt for the fuzziness of mind that will suggest a wonderful subject for an article without knowing who is to write it, is essentially the same as his refusal to tolerate the ugliness of a badly-spaced line.

To encounter these qualities from the point of view of a contributor was a deeply educative and reassuring experience. In his treatment of writers Karl showed that a good editor is like a good teacher, both of whom know how to elicit the best from another mind without unduly influencing it. The editor, however, has far less time to do this than the teacher, and Karl seemed to have an almost mesmeric power to get one to produce copy as well and as quickly as one could.

To work alongside him in an office was an intense and unforgettable experience, frequently inspiring, always invigorating, never less than interesting, sometimes very uncomfortable. He has a tremendous sense of humour, which characteristically emerges suddenly from a moment of scowling annoyance. Few people can be as funny as he is. Even when he is irritated and in the heat of trying to get something done his remarks can be shot through with frantic hilarity:

Karl: Madeleine, will you get me Frank Kermode on the telephone.

Madeleine (after trying): He’s not there.

Karl: How do you know he’s not there? May be he just didn’t pick the phone up

Once when the phone rang at a particularly critical juncture, Karl yelled: ‘If it’s Oliver Sacks, don’t answer it’. But nothing quite expresses for me the intensity with which he pursued his aims at the LRB than the image of him coming through the door one Monday morning at 6A Bedford Square (where we had offices in the early Eighties). For the second time in a month, we had been burgled. The office was upside down. The petty cash tin lay raped on the floor. And the burglar, to get in, had smashed a gaping hole in the wooden panel of the door, which was now unlocked. Without bothering to try the handle, Karl climbed through the jagged hole, walked unseeing through the debris, sat down at his desk and started the day.

Soon after I started work at the London Review, in 1982, I lost my temper with Karl and raged at him and stormed out of the room. A while later he stopped by my desk on his way out of the office and said: ‘Don’t you worry about it. I lose my temper too. Some people say I lose it rather often – several times a day, as a matter of fact. I like it. It shows you care’.

Karl’s going opens a fresh chapter in the paper’s history. But the LRB is a collective venture, and with Mary-Kay Wilmers continuing as editor, the tradition which she and Karl Miller have established will remain in all fundamental respects undisturbed.

Send Letters To:

The Editor

London Review of Books,

28 Little Russell Street

London, WC1A 2HN

letters@lrb.co.uk

Please include name, address, and a telephone number.