There are really only two things people want to keep from public scrutiny: their real, private self; or the fact that they have no private self of any particular interest. Now, my instinctive guess is that everyone is nursing the fear that the real them doesn’t amount to very much worth knowing. The famous fear it most, but everyone, I think, suspects that they might not really exist in any interesting way beyond their public and superficial selves. Still, some part of me rebels at this thought, if only because it’s so dull. Surely, there might be some individuals whose exterior and apparent love of themselves and all their works is genuine adoration for what they find in the privacy of their own self-regard. It’s not my experience of how human beings are, but I might have missed something. I look, therefore, with great interest, at self-revelation and where its limits lie.

I had hopes of Sex. Wouldn’t Madonna offer us her limitless confidence and dispel my nagging doubt that we all suffer from nagging doubts? Wouldn’t she be saying: you’ve had the public stuff, now here’s the raw material, the motherlode. All of it’s worth having, and therefore all of it’s available for public scrutiny. The private outer and inner self, which previously had been occluded by art and artifice, would now be displayed in its pure form, not needing the camouflage of false reticence. Here are the naked breasts, thighs, buttocks, pubis, as well as the equally naked inner thoughts, the secret fantasies, the mind. Madonna, I hoped, knowing her own value, would give herself like a stick of rock: every part of her could be sucked, and ‘self-worth’ found written right through her. Call me a romantic, but I want to find a righteous arrogance that has no need to protect the secret self with disclaimers.

Sadly, it’s not between the aluminium covers of Sex. Before I’d laid eyes on the first nipple-ring, I read: ‘by the way, any similarity between characters and events depicted in this book and real persons is not only purely coincidental, it’s ridiculous. Nothing in this book is true.’ I might as well have closed the book there and then, but I’d been allotted two hours alone with it in an executive’s office in Michelin House. When again would I have the opportunity to sit at an eight-foot glass desk, in a room containing nothing but several sofas and a tree, with a view of a giant Michelin man waving at me through the glass wall? Also, I had signed a formidable piece of paper promising on pain of something so terrible it could not be stated, that I would not breathe a word of what I was about to see to anyone before publication day. How could I not tell of what I had not seen? So I turned the pages.

I’ve never gone along with the usual liberal response to pornography that it is so boring. If sex is exciting (and you won’t find a liberal to deny that) then pornography must be exciting, at least if it’s well done. This, however, wasn’t. In words and pictures (the latter being as stilted as the former), Madonna displays the full range of sexual fantasy from anal to bestial. If Still Life with Dog, or Portrait of Three Naked Girls on a Bed, turns you on, then this is for you, but only if you are excited by those practices being no more than signified. The represented activities might as well have been replaced by labels planted where the actors stand, kneel or lie. The word ‘blade’ placed perpendicular to the phrase ‘leather-covered labia’ would, I think, stimulate the imagination more than the static pictorial version with Madonna and her chums. (It’s a pity, really, that no one thought of a pop-up book: the tableaux might then have attained all the waxwork power of Charlotte Corday’s knife arm moving mechanically up and down in Madame Tussaud’s re-creation of Marat’s murder.) But perhaps the posed disappointment is true of any soft porn magazine you might buy (if you can reach) from the top shelf of the newsagent.

What you wouldn’t have to put up with from Spanking Monthly (apart from a £25 price tag and cheap paper) are the regular warnings and denials Madonna sprinkles through the text. ‘Everything you are about to see and read is a fantasy ... But if I were to make my dreams real, I would certainly use condoms.’ ‘Ass fucking is the most pleasurable way ... but if you’re not doing it right things can really go wrong.’ ‘It’s how you treat people in everyday life that counts ... I wouldn’t want to watch anyone get really hurt, male or female.’ Go ahead, let rip, but be very careful, and incidentally, I don’t mean any of this, is not the language of revelation, in any sense. At the end, everyone is thanked for their ‘courage’. I saw none, nor, if it comes to that, any indication of style or desire.

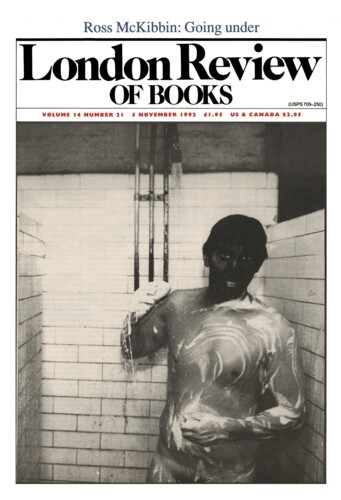

Revelation beyond that of flesh unclothed was too much to demand, I suppose, but surely eroticism was not an unreasonable expectation? What’s missing here is effectively simulated obsession, without which any attempt at the erotic might as well pack up and go home. No one told Madonna or her photographer that open thighs, peekaboo leather bras, a multigendered melée on a sofa, or a finger slid under a knickered crotch are only sexy if the camera lens, representing the voyeur’s eye, is obsessed with seeing what it is not supposed to see. Of course, that’s a fake, too, but good pornography knows how to tell a story. Only a single shot even begins to do this, and that’s the one everyone has seen, with Madonna, back to camera, wearing boots and a Gap vest, looking out of a window, with one hand idly fiddling between the back of her thighs.

People keep joking, ‘What’s she looking at?’ But that’s the point. It comes near to giving the impression that she’s been caught off guard, that what we are seeing is a private easy familiarity with herself. She’s thinking about something else, and toying with herself lazily. We become peepers and she becomes, for the first time, an object of interest. It’s almost a fine piece of porn. Then you turn the page, and there are half a dozen people pointing their private parts at the camera, giggling, or trying to look very serious, and the Michelin man seems more enticing.

So, Madonna fails as the queen of self-revelation, but she’s not the only girl in the game. Julie Burchill has a book out, too. Airing opinions in magazines and tabloids is another kind of stripping bare. Burchill, more than anybody, yells, ‘This is me’ as she tells you in fifteen hundred words or less what she thinks about what’s what. There’s nothing that could be called false modesty lurking in her contempt for Hampstead intellectual wankers, patronising First World Greens, and middle-class socio-psycho-babblers. It’s a dangerous business collecting bits of journalism together in one place. A column of biting vituperation becomes an indeterminate fishwife shriek when multiplied by 250 pages. And a racy style loses its edge when someone has forgotten to edit out the repeated use of the same phrases (‘fiscal not physical’, ‘powerless dressing’, ‘the difference between self-defence and suicide’) which, at best, are only striking the first time you read them. I’m glad someone’s out there pointing the finger at the Wankers, the Greens and the Babblers. She’s right for the most part; the parade is pitiful, and the cultural establishment a great deal less thoughtful and less clever than it thinks itself to be. She might well rail against the insularity of Amis, Drabble, Mortimer and Rushdie, but it’s a pity that all she can shame them with is Marilyn Monroe, Jim Morrison, Sylvia Plath and Marvin Gaye.

Being attracted to doomed and self-destructive talents, rather than trudging old plodders who don’t have anything very startling to say, is understandable, but as with the Madonna book, when it comes to self-revelation time, there’s nothing very original to be found. A kind of What Makes Burchill Run? piece at the end functions as self-explanation. Her main credentials are that she’s a working-class girl from the sticks (like Madonna); an outsider who took the world of letters (or at any rate the NME) by storm, very young, very fast and ever so iconoclastic. And why? Not luck: enormous talent. She ‘made it look effortless, like a skater, and you can only make it look effortless if you have a lot of talent. My greatest gift, apart from my talent itself and my big green eyes, has been this: an ability to combine the modus operandi of the simple person with the perceptions of the complex person.’ I read this and long to think I have found the righteous arrogance I was looking for. But negating a bunch of half-baked fashion-bound political and social theories by naming dead stars is not good enough. And the bold, new, populist vision of culture she offers (drugs, drink, fin-de-Siècle desperation and contempt for all things Sixties and Seventies) looks very like the quaint old-fashioned existentialism of the Fifties, with a dash of careful anarchy thrown in. All the green eyes, talent and complexity in the world can’t make that much more than a repetition of a tale already told.

When it comes to self-revelation, Fiona Pitt-Kethley’s volume makes Madonna’s bared bits and bobs look like a suburban room-setting in House and Garden. It is not, however, quite the triumph of self-knowledge I was after. There’s a certain bravado in publishing a collection of rejected articles. But even though there are none the world couldn’t live without, it was not the essays which made me finally abandon, and deeply regret my search for the revealing self. The latter part of the book is taken up with a series of letters written over a period of years by Pitt-Kethley to Hugo Williams, in the hope that he would finally come to requite her love for him. She offers these letters to the world as evidence of her real self. They are truer than her other writing, she says, because ‘they reveal all of myself – the tender side as well as the hard, cynical outsider.’ They are also, she tells us, witty, charming and contain the full repertoire of her emotions. She decided to publish them when, contrary to her view of them, Williams described the letters as ‘dreary and boring.’ At last, I thought. But beginning to read, I started to wish myself away, back to the fabrication and self-concealment of fiction, where bad judgment and lack of self-knowledge have somewhere to hide. Passing over the elementary, but essential truth that people who do not love you cannot be made to do so, all I can say, now, to anyone who might be contemplating self-revelation is: don’t. You might be lucky and merely fail to deliver the goods. But if you succeed, what you risk revealing is how very little you know about yourself, and the great disparity between what you think you have shown, and what is seen. If you’ve got copies of letters you’ve written to an unwilling lover lying around, burn them. Do it, now.

Send Letters To:

The Editor

London Review of Books,

28 Little Russell Street

London, WC1A 2HN

letters@lrb.co.uk

Please include name, address, and a telephone number.