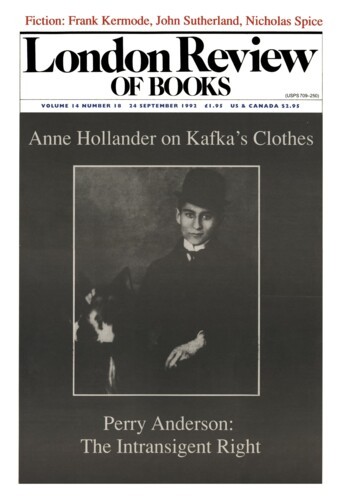

The jacket photo for Kafka’s Clothes shows him without any, sitting tailor-fashion on a beach, smiling above naked shoulders and a thin chest, the prominent ears rhyming with prominent bony knees. His swimming trunks are obscured in shadow. It’s not at all the stiff-collared, well-buttoned Kafka we’re used to, and the one introduced in the interior of this study is also unfamiliar. But he is convincing. Clothes might seem to be among the least of Kafka’s interests, since he is usually taken as a dedicated visionary, struggling only to purify his mode of expression in order to probe more keenly into the most painful matters of life and death and men’s souls, and he is remembered as someone unworldly enough to break off his engagement in order to give himself only to his work. Mark Anderson has nevertheless shown that clothes mattered hugely to him.

Clothes have always made a very useful literary metaphor (language is the dress of thought, and so on), and they have also offered a useful descriptive device for most novelists, however surreal their vision. Simply finding instances of Kafka’s use of each would not prove that he was unusually alert to costume. But Anderson’s larger purpose is to reconnect Kafka with the worldly world from which he came, and to show that he felt himself obliged to deal with it and live in it, to consider his place inside literary and human history instead of instantly vanishing into the thin air of Modern Literature, where many readers have wished to keep him suspended.

Clothes exist to remind the self of the body, and to create a worldly body for each person. Anderson connects them with Kafka’s interest in bodily states and qualities, both his own and those of his characters, as well as with his literary technique, with the skilful cut of his fictional language that created a unified body for his work. Anderson sees dress as a pivotal metaphor in Kafka’s private thought, where it mainly stands for the mobile world of human exchange – at once vain and nourishing, both hampering to spiritual and artistic clarity and vital to continuing life. Clothing is itself entirely malleable, like language and art, infinitely adaptable to alterations in form that change its meaning. Getting free of clothes is impossible; one simply gets into a different costume.

Anderson’s idea about Kafka makes sense in view of two sets of circumstances, one being the cultural ambience in Prague and Vienna during Kafka’s youth, the other being the fact that Kafka’s father ran a wholesale dress-accessories business, buying and selling all sons of useless and captivating fashionable adornments. He knew his father’s shop, but never had to work there, nor engage directly in the fancy-goods trade, like Gregor Samsa. He was free to observe the fashion business from an intellectual distance, but never free of it, nor indeed free to think he should be. He had moreover an excellent eye for fashion, as letters and journals attest. During his young days as a literary aesthete, Kafka dressed with extreme elegance, subscribing to the Wildean theory that one must be a work of art or wear one – by which was meant that one must do both – and thus following the creed that life itself should perpetually be transformed into art. Fin-de-Siècle dandyism was based on the notion that clothes could accomplish this.

Kafka’s youthful writings were also realised in the somewhat precious and purple style identified with Decadence, which at the time was felt to be an expression of opposition to stuffy bourgeois values, a search for Beauty that rejected antimacassars and buttoned boots. Later, Kafka said that he wished to be made of literature, but by then he had discovered that turning oneself into writing meant constant hard work and sacrifice, not simply adopting a literary costume and posture. But he never gave up the work of dandyism, either. Anderson describes him during his last two years of life in Berlin, poor and ill, but insisting on excellent clothes made by a tailor he could not afford, to sustain the physical image of a transcendent, co-ordinated self. He had retained his devotion to a bodily fastidiousness that expressed a desire for clarity and unity of form in art; he admired a cleanliness and limberness of performance that seamlessly identified the physical with the artistic self.

It appears that Kafka was personally interested in the body-culture systems that flourished in German society at the time, and that he followed for years the gymnastic manual of one J.P. Müller, which had a picture of the Apoxyomenos on the cover and photos of the author inside, a mustachioed version solemnly demonstrating the prescribed movements in the nude. Kafka was also interested in the Eurythmics of Dalcroze, and visited his school; and he was interested in the Dress Reform movement, on which he attended lectures. But gymnastics and acrobatics especially fascinated Kafka, who felt himself to be too tall, too thin, too awkward and physically fragmented. His early devotion to sartorial elegance was among other things an attempt to harmonise himself, an effort continued by his body-building regime. His health did give way to tuberculosis, despite all the Müller exercises, the vegetarian diet, the abstinence from alcohol, the many hikes in the country. But the bodily effort had not been made to cheat physical death. Linked to the well-cut suits and to similar efforts in his writing, it was a bid for aesthetic immortality; and that he achieved.

He achieved it against certain formidable cultural and personal odds, well described by Anderson. Like its cousin the Art Nouveau, the Jugendstil movement was trying to make life beautiful by retreating from vulgar commerce and crude sexuality, and it created a decorative and artistic style that seemed to lack force; somewhat later, Adolf Loos and Karl Kraus held that all ornament was criminal, and that civilisation only advanced to the degree that it rejected embellishment altogether, so that the resultant artifacts suggested a certain sterility along with their undoubted strength. Both negative notions of the proper aims of art flourished in young Kafka’s Prague, offering the idea that new art, in order to transform life, required some kind of withdrawal from it. It was a seductive thought for many artists. But these ideas did not offer a way for Kafka to move forward – to avoid a self-limiting retreat, but nevertheless to transcend what Anderson calls ‘the Traffic of Clothes’.

He uses this phrase to mean the aspect of life embodied in his father’s business, the style of temporal living that turns existence itself (which necessarily includes art) into a set of aimless exchanges, a perpetual ‘travelling’ that is mobile yet confining, false and distracting, erotic but joyless, incapable of acknowledging and articulating psychological truth, or of permitting the exercise of a natural dynamic energy that could make something new and authentically beautiful – something modern. Aestheticism turned out to be offering essentially the same false thing, disguised by a new style. There is a deep conflict suggested by the fact that clothes, if they are at all interesting, seductive and complex, whether they are made in the stiffly-layered, ruffle-trimmed bourgeois style or in the trailing gauzes adorned with iridescent arabesques favoured by the Jugendstil, are difficult to keep clean and free of disharmonious wrinkles. Kafka often mentions the dirtiness of dress, as if it were built-in.

It is interesting to note, although Anderson does not emphasise this much, that for all the Dress Reform people, and apparently for Kafka too, the most false and distracting clothes, and the unfailingly dirtiest, were women’s clothes. They were of course the whole substance of Papa’s concern. We don’t hear of him dealing in cravats and embroidered gentlemen’s waistcoats, only lace collars and fringed parasols and the like. Ordinary women’s clothes of the time, the pleated skirts and tucked shirtwaists, to say nothing of the jackets with passementerie and the hats with ribbons and the complicated underwear, seemed full of some profound unwholesomeness. They constituted a drag on spiritual aspiration and clear thinking that was somehow even worse than the one lurking in the multiple buttons and lapels, the starched shirts, stiff bowler hats and cuffed trousers, affected by the male sex.

Women themselves were often then seen to be entirely devoted to Traffic, to human intercourse, sexual, social, and especially familial, to fashion, which keeps urging trivial shifts in custom and appearance, to the unreflective, repetitive and unending busyness of house keeping and shopping; and to commercial sexual traffic if they were prostitutes, another métier requiring endless repetition and exchange. Female dress with all its compromised lack of straightforwardness could easily seem the same as female life, so that if a woman appeared to be nothing but her clothing, she could even seem to be taking on her proper responsibilities as a woman. A male artist could only view her from an entranced and baffled distance, unless he wished to tangle with those easily soiled and creased petticoats.

Men, however, were the ones who wanted to be artists, to bound like free-swinging nude acrobats above the flow of Traffic, to attempt the journey out of time and the river. And men’s clothes, as opposed to women’s – Anderson touches on this only at the end of his story – do offer a way out. The beauty of perfect male tailoring has in it the possibilities for transcendent modern abstraction that Beau Brummell originally saw in it. The perfectly-cut suit, so perfect that it is unnoticeable, can finally create a perfect nakedness for the imperfect, disharmonious body of the aspiring artist. A writer may proudly wear it in Elysium, where it can rightly show his true genius to be free of ornamental lumber and awkward posing.

But Kafka, with all his swiftly crystallised artistic ambition, was nevertheless deeply ambivalent about the aspect of life embodied in pleated skirts and passementerie, or indeed in elegant dress suits and gleaming neckwear. He keenly felt the appeal of attractive clothes for both sexes, of sex itself, and of art in its erotic guises. Anderson demonstrates his debt to Huysmans, Octave Mirbeau and Sacher-Masoch, to Baudelaire fully as much as to Flaubert. Withdrawing from all this was not psychologically or morally possible for the artist Kafka was becoming; backing away meant weakness, bad faith and lack of conviction. Anderson shows that instead of this his ultimate strategy was head-on vigorous attack, straight through and out the other side. For Kafka, writing was a journey of no return on the religious model.

And so we get ‘The Metamorphosis’. Gregor, the fearsome beetle, clad in his functional carapace, is the new-made Modern Artist, the ultimate gymnast free to walk on the ceiling and fall without harm, who makes ultimate mockery not only of overstuffed chairs and polite behaviour, of the dress-goods business and of domestic hopes, but of all the old realities – especially artistic ones. This includes the idea at the core of 19th-century novels: that clothes, like facial and bodily traits, always correctly express character. Persons in clean respectable costume are honest and hardworking; persons in showy and flimsy garb are dishonest and morally loose; persons in dirty garments are lazy and unscrupulous, just as persons with sensual lips are sexually susceptible and probably gluttonous, whereas those with tight lips are naturally abstemious.

Horrifying to his family, Gregor’s new ‘natural body’ is beautifully articulated and abstract, like other natural forms and like the frightening emergent forms of modern art, although it is just as far from the costume of Greek nudity, or from Reform Dress, as it is from ruffles and tight business suits. It shows how form in bodies and clothes, and form in art, can climb free of limiting convention in the modern universe. There, one can see the thing itself, and nothing else. Gregor represents Kafka transformed into writing, as he desired to be. His body, dressed in its perfect animal garment, aspires to the condition of music: but it compromises all life’s homely rituals, and it can’t comfort him.

The power of form is manifest in the incomprehensible garments of the officials in The Trial, whose badges and straps and buckled flaps are the more terrifying to Joseph K. because they seem to have a significance out of his mind’s reach. Joseph K. himself begins by believing himself guilty of nothing. But when he agrees to wear his own conventional black suit for this trial, he puts on the garment of guilt that gradually becomes the truth about him. Ordinary clothes don’t express the inner truth of the man so much as they create it, working from the outside in. They have the power, initially granted them by human imagination and desire, to create the human world, its inner condition as well as its visible one. It’s foolish to believe one can retreat from them: but it’s imperative for a serious artist (or a free soul) to confront them creatively and use them to his advantage, unlike that hopelessly un-free soul and non-artist, Joseph K., guilty of imprisonment in the busy and disorderly movement of human traffic, incapable of transcendence. He is finally made of clothes; he has given in to the paternal order.

The frightful machine in In the Penal Colony, mechanically inscribing the condemned man’s judgment onto his living body with needles that embellish the words with an elaborate decorative accompaniment, demonstrates Kafka’s knowledge that he needed to feel the mindless harm of excessive literary ornament in his system, or under his skin, in order to get beyond it, and attain redemption through a transfigured form of writing. The punitive character of the situation seems to reflect Kafka’s recent rejection of his fiancée, and his awareness that his murder of love had dreadful costs. The appropriate garment for the perfectly performing writer is a transcendent literary one, worn at the price of great travail and pain. Certainly no fashionable ‘travelling costume’, the strapped-and-belted, fake-efficient kind of outfit that Anderson finds Kafka most fascinated and repelled by, can properly fit him for his task, but nostalgic nakedness and draperies will not do so either.

Anderson’s book gives us a Kafka much more involved in issues of dress than the unclad bug of his famous story would at first suggest. We have held onto the idea that the topic of clothes can’t penetrate intellectual discussion – literary criticism, for example – without somehow debasing it. This book is a fine example to the contrary. I do have a quarrel with its subtitle, however, because the book is not about ornament and aestheticism so much as about their effect on a remarkable writer. Maybe it should have been called ‘Kafka’s Clothes, and How he got out of them’; it would go well with the jacket photo.

Send Letters To:

The Editor

London Review of Books,

28 Little Russell Street

London, WC1A 2HN

letters@lrb.co.uk

Please include name, address, and a telephone number.