‘In later life I have been sometimes praised, sometimes mocked, for my way of pointing out the mythical elements that seem to me to underlie our apparently ordinary lives.’ Dunstan Ramsay, the hero of Robertson Davies’s Fifth Business, says this; but one can assume that Davies is also talking about the reception of his own novels. To reduce character and incident to their ‘mythical elements’ can be criticised as an evasion of the novelist’s proper task, which is to document the social arrangements of a specific time and place.

The classic British novel represents these arrangements on two levels at once. People do things for material reasons, but they also strive to achieve grace within a complex hierarchy of status. Canada lacks such a fine-grained system of social differentiation; nor, looking south rather than east, does it have the exalted national myths that have swept the American novel along since Cooper and Melville. The Canadian novelistic territory that Davies exploits is one where myth is intertwined with everyday concerns, and is active mainly within the horizon of an individual life. With Iris Murdoch or Anthony Powell – Davies’s closest equivalents among British novelists – mythic seriousness cohabits somewhat uneasily with social comedy. On the other side of the Atlantic, a mythic hero like Bellow’s Henderson the Rain King also bears the political weight of his nation’s encounters with the Third World. In the milder Canadian setting, Davies can place a domesticated myth more comfortably at centre stage, less overshadowed by any rival powers.

Murther and Walking Spirits, which Davies says will be his last novel, is a playful blending of his favourite artistic ingredients: myth, drama, Jungian psychology and Canadian identity. In the first sentence its narrator, Connor Gilmartin, is murdered by his wife’s lover. Still conscious of the world, though no longer present in it, Gilmartin’s ghost – if that is the right word – sees both the investigation of his own death and episodes from some two hundred years of his family history. The novel’s premise, borrowed from Jung, is that each individual sits at the top of a psychic root-system that extends from immediate ancestors all the way down to a collective national character. These roots are revealed to Gilmartin when he posthumously attends a film festival. Each of the five films shown is a forgotten masterpiece, lately reconstructed by film scholars. For Gilmartin they become a series of scenes, in different styles, from his own ancestral past: ‘captured, as a film captures experience, in a narrative that is coherent as what we call real life can never be.’

Gilmartin is bewildered by his entrapment in such ‘delusions of reference’, where the external world seems to reflect back his personal concerns. When alive, he had ‘never thought about ancestors, or expected to be proud of ancestors’. Resurrected for him on film, ‘they seem as far-off and strange as so many Trobriand Islanders.’ Yet they have turned up on his psychic doorstep, demanding to be let in. One set of these ancestors are Empire Loyalists, who fled to Canada after the American Revolution to preserve what they could of their way of life. The other set are Welsh Methodist cloth-traders, who declined in the Old World and hoped to restore their standing in the New. Gilmartin’s ancestors have a great deal in common with Davies’s own. Whether or not one agrees that ancestors still live in their descendants, it must be the case that the collective personality of a country is built up over generations on some principle of continuity. In Canada, national identity has grown from the decisions of a series of deprived or defeated peoples to come here, and to bring their emotional baggage along. The motto of Quebec, Je me souviens, affirms solidarity with the Breton and Norman colony of New France, as it existed before its defeat on the Plains of Abraham in 1759. In Toronto and Vancouver, conversely, we find Post-Modern cities built on a displacement of memory: cities where some 40 per cent of the inhabitants were born in a foreign country, and still have a spiritual bond with it. The US enjoins its newcomers to forget the past and embrace the American way; Canada may offer opportunity or refuge, but no obligatory national dream.

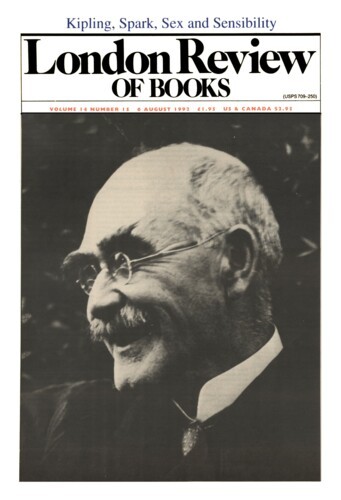

Davies himself has been a kind of twice-born Canadian, familiar with the different states of being settled in one’s country, leaving it, and then choosing to return. He was born into the Ontario upper-middle class in 1913, and educated at two of its traditional preserves, Upper Canada College and Queens University. He then went to Balliol, where he wrote a thesis on Shakespeare’s boy actors. After Oxford he joined the Old Vic as an actor and lecturer on the history of the theatre. In 1940 he returned to Canada and spent twenty years as editor of a small-town newspaper, followed by a third career as Professor of English and Drama at the University of Toronto. Meanwhile he wrote many plays and novels, but it was not until the publication of Fifth Business in 1970 that he established himself as a major Canadian novelist. The Manticore and World of Wonders completed the Deptford trilogy, which was followed by the Cornish trilogy of The Rebel Angels, What’s bred in the bone, and The Lyre of Orpheus.

The wealthy expatriate Francis Cornish, hero of What’s bred in the bone, returns to Canada after the Second World War to do something for his own country’s art. It seems probable that Davies had similar reasons for corning home, though it took him thirty years to achieve mastery, as a novelist, of the cultural situation in which he found himself. Superficially, there has been a persistent British flavour in Davies’s novels, and this has perhaps boosted his popularity with American readers, encouraging them to fantasise that the world of Brideshead Revisited can still be found north of the 49th parallel. Yet such Anglicised social comedy, often placed in an academic setting, seems to me the weakest component of his fiction (apart from having very little to do with the realities of Canadian academic life). The institutions that Davies writes about with true insight and affection are small towns and the theatre. One of the best sections of What’s bred in the bone describes growing up in a small Ottawa valley town, Blairlogie, before the First World War; and Davies always writes fascinatingly about the world of backstage, from travelling carnival (World of Wonders) to opera (The Lyre of Orpheus). His professors and journalists are too histrionic to carry conviction: but in the theatre, eccentricity and self-indulgence are everyone’s legitimate stock-in-trade.

The individual flamboyance of Davies’s characters contrasts with the neutrality of the public sphere that contains them. An Englishwoman remarks, in What’s bred in the bone, that ‘Canada is an introverted country.’ Davies has never sought in his novels to assert a willed national identity. Rather, the absence of distinctive national traits and ambitions leaves room for a wider reverberation of individual experiences. The Deptford trilogy begins with a miscarriage brought on by a stone in a snowball; it ends when the person who threw it kills himself sixty years later, with the same stone in his mouth. But Davies does not dwell on the idea that it was an archetypally Canadian snowball. The task that life sets his characters is to discover their ‘personal mythologies’ – not their relation to a national one. Everyday events like throwing a snowball, having dinner with friends or furnishing a house are universal rather than national: that is why they can more easily open a door into the mythic dimension, and make a character’s life part of some larger pattern.

Personal myths are therefore inconsistent with public ones like Manifest Destiny or Ruling the Waves. Indeed, in his trilogies the myths are not even consistent with each other. Each novel presents events from the point of view of a different character; each narrator holds different pieces of the puzzle, and fits them into his own version of the plot. Being the hero of one’s own tale does not preclude being the butt of someone else’s: as Hugh McWearie says in Murther and Walking Spirits, ‘one’s family is made up of supporting players in one’s personal drama.’ The novelist and his readers, who see all sides, must view the narrators’ pretensions with irony: but Davies proposes that we should still have the courage to make our lives into myth, even if our commitment seems absurd or incomprehensible to everyone else.

In Murther and Walking Spirits, he explores another kind of solipsism. One of the films that Connor Gilmartin sees is the story of his great-great-great-great-grandmother, Anna Gage, the widow of a British major, who flees from the triumphant American Revolution by paddling a canoe from New York City to Lake Ontario. Canada is for her a country without a mob, less likely to persecute those who fail to subscribe to the national myth. On the father’s side of the family, the Gilmartins are Welsh: itinerant Methodist preachers, cloth-traders, and intellectuals. Somewhere in each person’s ragbag of family legends, Davies suggests, can be found the myth that can save us in the rationalised modern world. Even if we cannot know our ancestors in any literal sense, they provide us with the stuff of dreams. It is on these terms that Connor Gilmartin comes to accept the queerly distorted films that he alone sees:

Whatever truth [the film] possesses is certainly not the historical truth I have been educated to think of as alone worthy of trust. In what I am watching, Time is conflated, as indeed it must be in any work of art. It is merciful of Whatever or Whoever is directing my existence at this moment to show the past as a work of art, for it was as a work of art that I tried to understand life, while I had life ...

Murther and Walking Spirits ends with Gilmartin seeing, from beyond the grave, a settling of accounts with his adulterous wife and his murderer. If Davies never fails to deal out poetic justice in his novels, his commitment to divine justice is less clear. Religion, often with a high Anglican flavour, figures prominently in the Cornish trilogy; and Davies tends to adopt a patronising tone towards those not interested in religious belief. On the other hand, religion never seems to prevent any of his characters from living with gusto, or from indulging in any of their favourite vices. In Fifth Business, Dunstan Ramsay claims that ‘religion and the Arabian Nights were true in the same way ... they were both psychologically rather than literally true.’

Both religion and the novel have the same root, therefore, in our love of tales and marvels. They are not reflections of the world ‘as it really is’, but things cobbled together from random scraps of art, fantasy and superstition; and science (or sociology) cannot be adequate creeds, because they offer us too barren a universe. Myth is needed, then, to make life more generous and surprising. A life must be founded on metaphor, Davies argues, if it is going to satisfy the one who must live it; and if it is, why care whether it is truth or lie?

Send Letters To:

The Editor

London Review of Books,

28 Little Russell Street

London, WC1A 2HN

letters@lrb.co.uk

Please include name, address, and a telephone number.