In Queen’s University, Belfast, in the Department of English, there is a plaque to a student who graduated in 1954. He was an outstanding student – brilliant, in the opinion of some of his tutors, and he had a great career ahead of him. On graduation he won a scholarship to Oxford to begin his doctoral research on the Metaphysical poets. He was my father.

His brilliant career never materialised and he died young, relatively young: by then, he had drifted half-way round the world, and when I last saw him, he seemed, in his uneven and untruthful way, to be trying to grope his way home. He was working for the BBC in London, he told me, and was preparing an important documentary on North Sea oil. This was in 1979.

Three days later he was dead: his body, however, was not discovered for three days more. He had been living alone in a shabby room in a dilapidated house owned by a Ukrainian, and it was high summer. On the landing, where anonymous feet scraped the lino by the pay phone, the first neighbour (if ‘neighbour’ is the right word here) paused and sniffed the air. A second neighbour joined the first. An hour later, the firemen broke down the door.

My father was a failure. Even I, who set no store by ambition or success, see him in this way. What’s worse, I suppose, is that he, too, from a young age saw himself in the same light. He attributed his failure to my mother, and to me.

I have seen the photographs. My mother was a very good-looking woman in her youth. She was small, slim, with thick brown hair that she wore in the style of Ingrid Bergman. She was not my father’s intellectual equal, nor his social equal. Her own father, born on the Falls Road, was a hard-working, quiet man whose last job was as a boardmarker in a bookie’s. My mother is immensely proud of her father, who died twenty-five years ago. At the time, at the time of her courtship and marriage to this son of an RUC sergeant, she had certain pretensions that came from a desire to see beyond the ghetto. She loved books and classical music.

I find her pretensions touching – I who bear my own origins with fierce pride, who despise those who seek to be different from the place that bred them. I forgive her her pretensions because, even though she was awed by the idea of sophistication, there was no element of the snob about her, no affectation, no trace of condescension. Little touches of these dreamy pretensions remain today, though really she has reverted to type. A Belfast woman, born on the Falls, who left school at 14 to work as a telephonist. That is what she is: but it is not what, in her heady courtship, she thought she would be.

She thought she would be transported into a different, more sophisticated world, a world she caught hints of only in novels and films. This man, whom she loved with a loyalty and passion I find impossible to comprehend, would take her into this world. Part of me, part of this woman’s son, maintains a distance from whatever I am in. That was not her way. She loved this man.

What did he get from her? A beautiful wife, yes. Devoted, adoring love, yes. And other things ... like ...

Like, he was a Protestant at a time when it was still fashionable in the intellectual circles to which he craved admittance to be Catholic, or better, a convert. She was a Catholic: devout, unquestioning. She had simple, rocklike faith, the kind seen by some as blindness, by others as profound. It depends on your point of view. From my father’s point of view, her naive Catholicism gave her a captivating and unaffected loveliness.

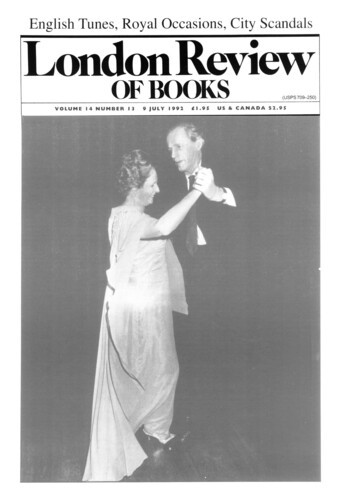

So she embodied something for him: the antithesis of his own feuding family. A bigoted father who fought the IRA and the Catholics, first in the ranks of the B-Specials, then in the RUC. This rigid, angry, self-loving man achieved his apotheosis at Buckingham Palace when he received his MBE. I, his grandson, look at the photographs of this occasion and can see only a flunky. I remember this man shouting at my mother, mocking her for her religion and her persistence in refusing to agree to divorce my father.

They joined, my mother and my father. Man and wife, Catholic and convert. They came together. But not for long. In Oxford, my father came up against his first disappointments. He was a provincial at a time when this was synonymous with being a yokel. Stunned, stung, bewildered, he adopted the first of many disguises: Terry became Simon. Then Simon took on and perfected an accent so English that his true origins were completely masked. Except to his wife: what did she think of this accent as it developed? Did he rehearse in front of her? What did she think these new and clipped vowels meant for her life and that of her child?

He discovered that having a wife was not in itself a source of embarrassment: but this wife was. She was not brilliant and she was no longer a simple girl. She was a straightforward girl whose simplicity had been undermined by her growing consciousness of a bigger, wider world. Her peasant simplicity, which would have been admired, was flawed by consciousness of a sophistication she could never attain, and which she only ever got half-right. I have seen a photograph of her at a party holding a cigarette in a holder. It almost made me cry, though she looks happy enough. It affected me because I see someone trying desperately to be accepted. By using a cigarette-holder. Men have fantasies of themselves as saviours: we can’t help it. Stories we hear turn into duties we imagine: a damsel in distress, a knight in armour. No matter what our shortcomings are in reality, we persist in seeing ourselves like this. My fantasy is to enter the photograph and snatch the cigarette-holder out of my mother’s mouth, then, defiantly, take her away from the people around her. And we will be heroic, because we have acted with integrity, shunning their falseness; and made more heroic because of the glares and hostility we will have provoked.

After that? It really is a fantasy. After that – nothing. I think my father, when he first looked at my mother in Belfast, at the trusting and beautiful face, must have had a similar fantasy. Take her away, take her away ...

But in the face of more disappointments, the fantasy palled. Burdened now with a screaming, demanding child as well as a wife, my father’s academic work went badly. He adopted another disguise: that of uncaring husband. To close on this new world he had to distance himself from the old: the old was represented by my mother and her fierce loyalties. My father started an affair: he discovered he was good at it. He started another, another. You could say the rest of his life was a series of affairs: Sonia in Peru, Chin in Malaysia, Emma in Los Angeles, Anita in London ...

Another disguise, or rather an extension of an existing disguise – brutality. My father, from what I have heard from his brother, was not a brutal man. He was the baby of the family, spoiled by a doting mother. In his youth he was quiet and bookish, and on occasions when he was confronted by violence he was shaken and appalled. But to show – to himself? to his new friends? – that he had sorted out his domestic life, that it was his to order and re-order at whim, his calculated unkindnesses turned to violence. My mother went to hospital.

For some years – I believe four – they stayed together. He was not a bad man and there were times when guilt overwhelmed him: there were days of kindness and love-making, and promises for the future.

The end came on my third birthday. It is my first memory. We lived in a small house in Banbury. But for my birthday party we were invited to the larger home of my godparents, English Catholics in Oxford. They had a lawn, long and flat with neat borders. My father – great joy! – my father played with me in the garden. We played football with balloons. I was deliriously, selfishly happy. I laughed and laughed. And my father picked me up and put me on his shoulders. He held me on his shoulders in the sun and threw balloons up into the air, and we ran after them and I, from my perch, tried to trap them in my arms.

My father put me down, took his jacket from a garden chair, hoisted it to his shoulder, put on a pair of sunglasses and smiled at me. I watched him approach the french windows, behind which I saw my mother. My father stood this side of the window, put his hand against the glass for a moment, and was gone. Tears streamed down my mother’s face. I can see her now, in my mind’s eye, in her summer dress and sandals, sobbing wretchedly.

The girlhood dream of sophistication had come truer than my mother could have imagined. She was from a place where there was no such thing as not knowing anyone, and loneliness was to her as mysterious as it was shameful. She could not bear the loneliness of England, and she returned to Belfast. She came from a large and cheerful family, but one well fastened by the boundaries they lived within and never sought to extend. My mother’s sad return was, I believe, for her brothers and sisters an object lesson in staying with what you know. My mother had breached some rule, had in some way got above herself, and had paid the penalty.

But they were not a cruel family, nor vindictive, and in time made enough room for my mother and me: and her rejoining of family and place was eased by her own disillusionment with the world of her husband. She became, once again, a Belfast girl, and her talk was no longer of Graham Greene and Aldous Huxley, but of Mrs Conroy’s operation.

Like to like. In later years my father’s veneer wore thinner and thinner. His terrible failures undermined his pretences: he never finished his doctorate, he never wrote his book. He never found anyone to replace my mother. For many years his disguises grew until they defined him, until they were, apparently, no longer disguises. But then, as his failures crowded in on him, they began to fall apart. To hold on to something, or simply because he had been beached and stranded, he came back to Belfast. Not to my mother, not to me; this story has no fairy-tale ending. He went to live with his warring parents.

Was there just a hint of Ulster breaking through the English accent now? I did not see him much in those last years, heard him talk even less. But I believe I did hear the disguised voice break once or twice. He kept up some pretences. How could he not? You cannot strip a man, even the weakest, most despicable man, you cannot strip him naked and parade him for all to see and mock: everyone deserves some cover. So, for all its transparency, I never challenged his cover.

After the death of his own father, my father went to London where he said he had important work to do for the BBC. He had a six-month contract, and would return after the documentary was completed. When we last met there was some hint, some promise, unspoken, of change to come, after his return.

He did not come back. At the time of his death he was working as a porter in Broadcasting House. His last supper had been fried steak and a bottle of vodka. The vodka made him drunk, the meat choked him.

In my writing there is always a father-son relationship, common enough in fiction, nothing unusual. But that is not the extent of Simon’s influence. I realise, and it is in my work, that there is no such thing as change in people. We think we can change, some people try hard for change, we always hope for it. But we are as we are, and not even the greatest of traumas will change us. When things go wrong, I will sweep an angry hand over the table, clearing the mess in one go, even at the cost of breaking the good and useful along with the distracting and useless. Like Simon, I have left everything behind on more than one occasion, starting afresh, completely afresh, unencumbered, clean, looking for change ...

Send Letters To:

The Editor

London Review of Books,

28 Little Russell Street

London, WC1A 2HN

letters@lrb.co.uk

Please include name, address, and a telephone number.