Within the first half-page of Toni Morrison’s novel, an 18-year-old girl has been shot dead by her middle-aged lover, and his wife has been manhandled from the funeral after attempting to cut the dead girl’s face with a knife. Both events are witnessed and kept secret by a community which has reason to distrust the police and to look kindly upon a hitherto gentle, childless couple, whose sudden, violent sorrows they recognise and are able to forgive. And as the spring of that year, 1926, bursts a month or two later upon the ‘City’ of this extraordinary novel, its all-seeing gossip of a narrator is moved to declare – if only provisionally – that ‘history is over, you all, and everything’s ahead at last.’

The novel’s theme tune is spun out from these contrasts and whirled through a series of playful improvisations by a storyteller who admits to being – and, as it turns out, expects the reader to be too – ‘curious, inventive and well-informed’. It is impossible to resist the seductions of this particular narrative voice as it announces its own fallibilities, mourns its distance from some of the events it will therefore need to invent, boldly revises its own speculations, even as it recalls, replays, retrieves them for us before our very eyes and with our assumed complicity. For, of course, this voice also undertakes to guarantee both tale and telling as truth, history, music known and shared by all who have roots in the black urban communities of America in the Twenties. And for readers with quite other roots? Well, the voice is no more prepared than Morrison is herself to ‘footnote the black experience for white readers’. As she put it in a recent interview: ‘I wouldn’t try to explain what a reader like me already knew.’

There are obscure sentences in this novel as in earlier ones, dense and elliptical passages, the consequence, perhaps, of a language drenched in speech and therefore off-hand at times with its secrets and avowals. Yet the lyricism and elasticity of Morrison’s writing come in part from her absolute faith in the fruits of a tension between what it is she knows and what she believes other people know or could know if they used their heads. Readers are ‘curious, inventive and well-informed’ too, as she knows. All Morrison’s novels have been crucially concerned with readers and with manipulative uses of literacy in racist societies. Her characters’ reading of newspapers, letters, ‘other people’s stories printed in small books’, are watched as signs of a politics, a whole way of reading the world. Her narrators are always conscious of their readers, and in this novel its musical elaborations are composed around the most flagrant toying with readerly expectations. At one moment there is a shameless revelling in what an imagination, forged through the minutest observation of physical detail and by the ordinary repetitiveness of life, can come up with; followed at once by a refusal to yield to the pull of either the inevitable or the apocalyptic. The novel’s quietly happy ending comes as a triumphant countering to the imagination’s more clamorous tendencies as, in a final aside, the narrator shrugs off the characters’ evasion of authorial vigilance as they put ‘their lives together in ways I never dreamed.’

Joe (the murderer), Violet (his wife) and Dorcas (the murdered girl) are all, though differently, orphans and people collected by the City through a series of migrations from the 1870s onward. Joe and Violet, the grandchildren of slaves and themselves members of a generation which shared a repertoire of horrors (torchings, evictions, riots, near-starvation) while rarely if ever choosing to talk about these things, are driven by the poverty and violence of their rural Southern lives, not just to Baltimore, but further, to the City. The journey they make there by train in 1906 may be cramped and occluded by a ‘green-as-poison curtain’ from the obsequious services lavished on the white passengers. Yet Joe and Violet experience it all as a dance of the most exhilarating anticipation and release, prefiguring the promise of the City itself: ‘They were hanging there, a young country couple, laughing and tapping back at the tracks, when the attendant came through, pleasant but unsmiling now that he didn’t have to smile in this car full of coloured people.’ Most aspects of their lives are characterised by a similar doubleness. Names and nicknames become witty creations in the teeth of a history which actually deprived people of names. Joe’s second name is Trace, the mistake he made as a child on hearing that his parents had ‘disappeared without trace’, and Violet is quickly renamed Violent by her astounded neighbours.

The dead girl, Dorcas, was orphaned by the riots of 1917 in East St Louis. Now she listens to the City’s siren songs of glamour and sexual bliss from the locked and neat apartment of her guardian aunt, who dreads above all for her niece the provocations of black music and the dancing it inspires. Dorcas bides her time. She has not yet flowered into beauty, and now never will. Her skin is still bad, tiny hoofmarks speckling her lower cheeks. If Joe is by no means what her dreams are made of, but a cosmetics salesman in his fifties with a wife, he loves her hopelessly, hoofmarks, callowness and all, and he showers her with gifts and promises. Even Dorcas’s disbelieving friend is bound to concede that ‘I think he likes women, and I don’t know anybody like that.’ Dorcas, however, longs for Acton, the cool young man who lets her dance with him. She dies marvelling at Acton’s fastidious attention to his jacket, now spattered with her blood.

The novel dwells less on the reasons for the murder, or even on the grief suffered in its wake by the murderer and his wife, than on a past which might be thought to have foretold these events. Spirited and consolatory lamentation provides an accompanying counterpoint, rich in echoes, remembered if unrecorded, of similar moments of desperation, pain, incomprehension. Joe has been haunted all his life by thoughts of his mother. He had grown up thinking her dead, but discovered at 18 that she is the wild woman who lives alone in the woods, an animal he has learned to laugh at and even torment. Violet, the third of the five children of a woman who drowned herself in a well, suppresses this and other terrors in her vigorous determination to survive in the City. But neither she nor Joe wants children. They have good memories too: a grandmother who laughed in the face of disaster, a friend called Victory, who listened. Like the City that they come to accept and even love, for its skies, its noise, its people, the past is alive with contra dietary energies, with kindnesses as astonishing as the cruelties.

In one prefiguring episode a young man, golden in beauty and in name, learns that his father was black and goes in search of him. Golden Gray, as his Southern belle of a mother has named him, stumbles upon the wild woman, just as she is giving birth to Joe. When he recoils from her, Morrison’s narrator wavers:

That is what makes me worry about him. How he thinks first of his clothes, and not the woman. How he checks the fastenings, but not her breath. It’s hard to get past that, but then he scrapes the mud from his Baltimore soles before he enters a cabin with a dirt floor and I don’t hate him much anymore.

Racism is the accumulation of particular moments for her characters, experienced from earliest childhood, never an abstraction, for Joe there is the memory of ‘two whitemen ... sitting on a rock. I sat on the ground right next to them until they got disgusted and moved off,’ Golden Gray is learning about this through his own well-tended finger-tips, and he is forgiven for the moment.

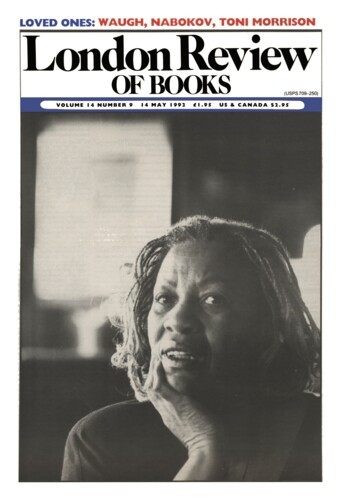

Apart from the briefest stutter at the very beginning of her writing life in the early Seventies, Toni Morrison’s career as a novelist has been greeted with gathering Superlatives. It is true that one or two ‘serious’ journals have published mean-spirited pieces arguing against her eligibility for Great American Writer status on the grounds that her concerns are too parochial. Yet even the most limiting and patronising reviews of her novels have acknowledged that they are ambitious achievements of exceptional originality and power. This, her sixth, is likely to be received with the same sort of enthusiasm. It may also be that it will be thought slighter than Beloved (her most recent novel) in some respects. It is shorter and its beauties are more contained. Readers report finding Beloved so unbearably painful to read at times that they needed to gather strength to go on. If the pain is less intense here, that may be because it is absorbed into the poetry, in a way that the blues reverberations make possible. Jazz seems to me to represent an advance in Morrison’s work; it is as subtly reliant on the processes of history as Beloved, and a novel of urban life to rival any other. A voice which hears the chorus of ‘slow moving whores, who never hurried anything but love’ chronicles the human part of the city beneath skies which separate and join the visible and the invisible.

Daylight slants like a razor cutting the buildings in half. In the top hall I see looking faces and it’s not easy to tell which are people, which are the work of stone masons. Below is shadow where any blasé thing takes place: clarinets and love-making, fists and the voices of sorrowful women.

It is a poetry grounded in fact. Violet dresses real heads of hair and feels a shift in the demand for her services like a draught directed at the nape of her neck. The watching, listening narrator is beguiled by more than music and light. People’s lives are very much their own business as well as other people’s. They have money to earn, meals to cook, apartments to furnish and clean. They think as actively while they wash as while they read. The details of a particular life are only to be understood as part of the pitfalls and aspirations of whole communities, even in the City. More than in any other novel I know of, the connections between country and city are preserved, as history, memory and loss.

Violet, it turns out, has had other lapses, or ‘cracks’. She once took someone else’s baby, though she returned it before any harm was done. The narrator explains:

I call them cracks because that is what they were. Not openings or breaks, but dark fissures in the globe light of the day. She wakes up in the morning and sees with perfect clarity a string of small, well-lit scenes. In each one something specific is being done: food things, work things; customers and acquaintances are encountered, places entered. But she does not see herself doing these things. She sees them being done.

Morrison has addressed all her novels to the need for black people to see themselves within a culture which does not encourage them to do so. Later in the novel, Dorcas’s young friend remembers the love scenes the two girls used to invent together and discuss, and she tells Violet:

Something about it bothered me, though. Not the loving stuff, but the picture I had of myself when I did it. Nothing like me. I saw myself as somebody I’d seen in a picture show or a magazine. Then it would work. If I pictured myself the way I am it seemed wrong.

Jazz is a love story, indeed a romance. And romance and its high-risk seductions for young women come with special health warnings when it is poor young black women who might succumb to it. For romance has always been white, popular, capitalistic in its account of love as transactions voluntarily undertaken between class and beauty and money. But the romance which is a snare and a delusion has also spelled out a future for young women, a destiny, significance and pleasure – and particularly when there was little enough of those possibilities for them or for the men they knew. The older women of Morrison’s novels know that sex can be a woman’s undoing, that men, ‘ridiculous and delicious and terrible’, are always trouble. The narrator in Jazz is generous with warnings: ‘The girls have red lips and their legs whisper to each other through silk stockings. The red lips and the silk flash power. A power they will exchange for the right to be overcome, penetrated.’

Morrison’s writing of a black romance pays its debt to blues music, the rhythms and the melancholy pleasures of which she has so magically transformed into a novel. More than that, she has claimed new sources and new kinds of reading as the inspiration for a thriving literature.

Send Letters To:

The Editor

London Review of Books,

28 Little Russell Street

London, WC1A 2HN

letters@lrb.co.uk

Please include name, address, and a telephone number.