For many people the BBC Foreign Affairs Editor John Simpson, who stayed behind in Baghdad when Armageddon was scheduled to begin, was the civilian hero of the Gulf War. The only thing that may have puzzled them was his title. How could a man edit reports coming from all quarters of the globe if he deliberately isolated himself under conditions of siege? On this matter From the House of War provides little help, except for a passing reference to the author’s ‘rather empty title’, which apparently carries important psychological impact when dealing with Iraqi (and other) civil servants, perhaps pandering, in the case of the Iraqis, to their notion that the whole world ought to be edited from Baghdad. One advantage of Simpson’s position is that in a crisis he seems to be able to post himself wherever he wants to be and to stay on, albeit with a scratch team, even when instructed by the BBC to leave. ‘You’ll have to get yourself a new foreign editor, then,’ he growled on being told to leave Baghdad, admitting now that he had been ‘probably much too heavy-handed in my response; I usually am.’ A large part of his motive was ‘the fact that I was writing a book’.

From the House of War is that book and one should say straight away that it is very good indeed: the best kind of journalist’s book. Any momentary unease about ‘the book’ figuring so prominently in the mind of a man whose job, after all, it is to give the instant version on the screen can be brushed aside: Simpson in no way appeared to viewers to be stinting his services to them. More generally, it should be said that the quality of television reporting, which is now the source of most people’s information, can only be sustained if reporters who convey the impression of being capable of writing a good book are given all the encouragement they can get. The primary medium, after all, is not naturally suited to lengthy narrative and nuanced thought and its product is to a high degree evanescent.

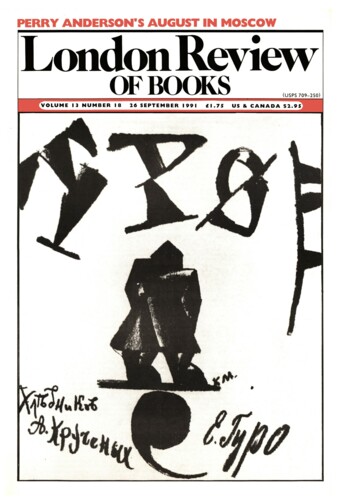

The outlet in print, which in weekly journalism used to be provided to BBC journalists by the Listener, is met now in the case of John Simpson by the Spectator and by the writing of books such as this. The London Review of Books, which has been publishing some of the high-class work of Stephen Sackur, a BBC radio reporter of the Gulf War and the Middle East generally, has recently brought out in paperback a collection of these pieces under the title On the Basra Road.* Radio and television reporters can be divided into those whom one would care to meet in print and the rest.

Though hastily published without an index, From the House of War, a book to be classed perhaps with William Howard Russell’s My Diary North and South on the opening phases of the American Civil War, is not at all carelessly written, nor is its quality impaired by periodic observations that remind one that the author is a television man. Indeed, that seems especially appropriate for a book about Saddam Hussein’s Iraq and Bush’s war against it. The Iraqis have a long habit of making publicly available their most embarrassing material. When I was in Baghdad for the BBC in 1969 (the first full year of the Baath regime) the Ministry of Information eagerly pressed on me stills of men hanging, with placards attached, in the central square, and videos of the Chief Rabbi and the General Secretary of the Communist Party reciting confessions on television (thus foreshadowing poor Farzad Bazoft by some twenty years). It was therefore fascinating to learn that Simpson had been shown a televised recording of the infamous session of the Revolution Command Council in 1979 at which Saddam celebrated his elevation to the Presidency after a decade as Number Two by accusing 60 associates of treason – 55 were found guilty and 22 executed.

From then on, it has been a battle of camera angles. Simpson describes Saddam as ‘an inveterate builder of testimonials to himself’ and thinks the Allies missed photo-opportunities that would have truly damaged Saddam by refraining from bombing these, particularly the one of Saddam’s own hands holding crossed scimitars, which used to appear every night just before the television news, with Saddam passing underneath on a white horse.

On certain matters Simpson reaches firm, though not unchallengeable opinions. He thinks Saddam decided to invade the whole of Kuwait on the spur of the moment, possibly as a result of a personal insult spat out by the Crown Prince of Kuwait at a rancorous negotiating session with the Iraqis, possibly because he was convinced that the Americans were going to intervene anyway, so thought he might as well go for broke. If the latter is correct (there is some evidence to support it), Ambassador April Glaspie’s role needs to be looked at in a new light. But it must be said that the military side of the invasion (though not the political) looked to Simpson’s BBC colleague Robert Fox, among others, to have been too carefully prepared an operation for that to be the case. Secondly, and quite contrary to the general belief, Simpson holds that Iraq was never a suitable case for treatment by economic sanctions. This is important because it is on the belief that Iraq was very – maybe even uniquely – vulnerable in this respect that the main criticism of Bush for pushing for early military action is based. Simpson is categorical: a country as fiercely controlled as Iraq could have lasted years under sanctions without being forced to withdraw from Kuwait.

Thirdly, his interpretation is throughout favourable to Yasser Arafat, a man who had a distinctly bad Gulf War. He awards Arafat the credit for advising Kuwait to temporise in the eve-of-invasion talks, for Saddam’s first admission of the possibility of a withdrawal from Kuwait, for Saddam’s decision to release all the hostages, for rendering ineffective the threats of a terrorist offensive against the West and for several of the last-minute attempts at reaching ‘an Arab solution’. Some of the evidence for this has to be Palestinian and Arafat is often infuriatingly ambiguous, as he was in the interview Simpson describes. Still, for him Arafat was ‘the rational, restraining voice in an absurd situation’. Fourthly, Simpson repeatedly says, quoting the Prime Minister of Spain, that Mrs Thatcher showed a ‘passion for war’. He thinks her intervention on the phone decided the Crown Prince of Kuwait to turn Saddam down flat.

Fifthly, as a result of his time in Iraq he warmly denies that crowds of Iraqi demonstrators displayed any genuine enthusiasm for Saddam Hussein and gets very cross with fellow journalists who kept conveying the opposite impression. Apart from ministers and officials, he says, ‘during nearly five months not a single Iraqi had defended Saddam Hussein to me in private... Some openly welcomed the coming war as their only hope of getting rid of a regime they hated. No Iraqi had ever once reproached me for the coming war.’

Sixthly, and most controversially of all he acquits George Bush of the criticism implied in Tam Dalyell’s remark that ‘if Kuwait had been famous for its carrots, the US would not have lifted its proverbial finger.’ Simpson thinks Bush so wanted to reassert American military power in an internationally acceptable framework that he would have moved at once to defend a carrot-growing victim of aggression. One can never really tell because the aggression against Kuwait combined almost every motive for taking a stand: but the degree to which the ‘new world order’ seems dependent on American logistics and political will is not reassuring.

Simpson reproaches American Intelligence with exaggerating the strength of the Iraqis mustered against them when Desert Storm began: 260,000 men, not 540,000, he says. Clearly Saddam had kept back far more troops than had been thought to deal with his really important enemies, those within in the Kurdish North and the Shiite areas round Basra. The implication here is that the Coalition could well have managed with far fewer troops. That may seem clear in retrospect, but General Schwarzkopf, another man who came well out of the war, was wise not to take any risks. According to his biographers, he had identified Iraq and her envy of Kuwait as the main source of danger in the vast area covered by his rather shadowy (and home-based) Central Command and had planned for that contingency. No one else in the American political and military establishment appears to have been gifted with the same foresight.

Much had been written in specialist American journals about the remarkable sophistication of ‘smart’ American weapons, and about the command, control and communications systems that were supposed to gain mastery of the battleground had there ever been a war in Central Europe, but the actual performance of American men and equipment in the minor actions in which they had been recently involved, including Grenada where Schwarzkopf had also been present though not in command, had left much to be desired. Scepticism as to whether ‘it would all come off on the night’ was widespread. It was not surprising that John Simpson did not really expect strikes that were genuinely surgical. His decision to stay was thus a gamble against what must have seemed heavy odds and suggests that Saddam may not have been the only one in Baghdad to have a touch of the Masada complex.

Any story of the reporting of the Gulf War inevitably contains elements of two journalistic side-battles: that of the pool reporters, living with the military, dressed in military clothes, conforming to military rules, against the free-wheeling unilaterals, and that of CNN versus everybody else. Sackur was with the pool, Simpson’s sympathies were with the unilaterals (the sight of Kate Adie in uniform clearly gave him a spasm). Some rather strong language was used at the time on both sides of the argument, which is rehearsed by these two writers with great moderation. Sackur is surely right in arguing that the military could not have had the vast press corps wandering about the battlefield. At the same time one is extremely grateful to Sandy Gall, Robert Fisk, Bob McKeon (the CBS correspondent who ‘liberated’ Kuwait city in the sense that Max Hastings ‘liberated’ the ‘Upland Goose’ in Port Stanley) and others who operated on their own, using their wits.

CNN, the wall-to-wall American news network, by means of which the world’s top public figures carefully study each other’s form (and the President of Turkey goes to the telephone because he has just seen Bush say he is about to call him), was allowed to stay on in Baghdad when the Iraqis decided they were going to do without the others. Even before that it had been granted special facilities. Like Nasser in 1956, Saddam was counting heavily on use of the psychological arm in making war against the West, and in return for staying in business, CNN has been suspected of being disposed to lend itself to this technique. Certainly it was allowed a permanent ‘four-wire’ line to the outside world on a military communications network. Saddam was hoping that CNN would show the world the kind of devastation that would generate waves of hostility against the coalition leadership. Simpson says that Iraqi officials planned to use the four-wire link in an emergency to activate whatever terrorist campaign had been planned. He and his crew kept trying to break free from their minders, communicating with London by satellite telephone when the Iraqis were not looking and striving to develop their own camera-angles which would show, if the security men let them (which they sometimes did not), the way in which a cruise missile would ‘turn left at the traffic lights’ on the way to its target.

Simpson holds that there was exaggeration about the size of the Iraqi casualties in the land battle. He quotes Robert Fox for the view that even at the notorious ‘turkey shoot’ at the Mutla ridge, where the retreating Iraqis were caught and obliterated by the massive weight of American power, there were not more than four hundred dead. Sackur describes the dreadful scene memorably in the title essay in On the Basra Road. ‘What threat could these pathetic remnants of Saddam Hussein’s beaten army have posed?’ he asks. ‘Wasn’t it obvious that the people of the convoy would have given themselves up willingly without the application of such ferocious weaponry?’ Simpson, ever aware of the media’s power, is probably right when he says that it was seeing pictures of this massacre that made President Bush call a halt to the fighting. Equally aware of the media’s power, Bush did not want the public mood to switch from rejoicing to revulsion. Ironically, it was this decision which in turn meant that other Iraqis in the Republican Guard were free to suppress the Shia revolt in Basra.

An engaging self-portrait emerges from Simpson’s story. He comes across as a man big enough to acknowledge his mistakes; with unusual tastes in people (he ends a pretty damning indictment of a ‘brutal’ censor called Mme Awatif with the touching remark, ‘I regarded her with respect and even liking,’ and describes himself as still ‘very fond’ of the Iraqi official who left his name off a vital list when in the end he left Baghdad, and denied him a visa to come back); capable of losing his cool; and with some undefined grievance against the Sixties – both Peter Arnett of CNN and the American Chargé d’Affaires, Joe Weston, are for ever condemned as being redolent of that era. It goes without saying that he is courageous in the best traditions of the war correspondent and is also competitive. He cannot forbear to note a surge of satisfaction when he observes an ITN cameraman whose athletic prowess had previously made him jealous standing at a perfect loss during the first air attack, although a sense of fairness obliges him to record that the next morning Brent Sadler of ITN, whose ‘style of reporting is not mine’, had been out in the streets whereas he had not. He was also very piqued at being beaten by Trevor McDonald in the competition for the Saddam Hussein interview, was unkind about McDonald in the Spectator (for which he expresses regret), and went off hurt from Iraq for a little while. He has a novelist’s gift for creating atmosphere and pinning down personalities, and a sense of humour. This does not desert him when he is sketching some of his colleagues, including his namesake Bob Simpson of BBC Radio, whom he describes as one of the heroes of the book and who, ‘infuriatingly attractive to women’, pursued an affair with one while under fire. ‘There’s nothing like a good jump when the rockets go up,’ he would cheerfully remark.

The early life of General H. Norman Schwarzkopf, son of General Herbert Norman Schwarzkopf, who was chief of the New Jersey State Police at the time of the Lindbergh baby murder and later formed and trained a gendarmerie for the Shah of Iran, is the story of a boy who hated the name Herbert so much that he had it wiped out by deed poll so that today the initial stands for nothing. He nevertheless automatically followed his father into the Army and went to West Point, where he gained renown as an all-round sportsman, using his exceptionally high IQ as a means of getting acceptable but not outstanding grades with the bare minimum of effort. There will be other lives of ‘the Bear’ whose post-Army career is only just beginning and very soon some memoirs of his own, but, partly thanks to Cohen’s and Gatti’s great good fortune in getting the full co-operation of the General’s favourite sister, In the Eye of the Storm is a very honourable first attempt.

Send Letters To:

The Editor

London Review of Books,

28 Little Russell Street

London, WC1A 2HN

letters@lrb.co.uk

Please include name, address, and a telephone number.