Seeing things, Seamus Heaney’s ninth volume of new poems, is aimed squarely at transcendence. The title has a humble and practical William Carlos Williams ring to it, but that is misleading. It is better understood as having been distilled from ‘I must be seeing things’, said seriously, and with a fair amount of stress on the ‘I must’.

The greatest difficulty for the poet is how to go on being one. Randall Jarrell set it out like this at the end of his essay on Stevens: ‘A man who is a good poet at 40 may turn out to be a good poet at 60; but he is more likely to have stopped writing poems, to be doing exercises in his own manner, or to have reverted to whatever commonplaces were popular when he was young. A good poet is someone who manages, in a lifetime of standing out in thunderstorms, to be struck by lightning five or six times; a dozen or two dozen times and he is great.’ This is poetry as catastrophe, as Minnesotan roulette. Heaney in his The Government of the Tongue quotes the Polish poet Anna Swir to similar but subtly different effect: according to her, the poet is ‘an antenna capturing the voices of the world’. Compared to the chilling folly of Jarrell, this is both pat and heroic. It is more statuesque, less adventitious, less calamitous. It allows less room both for the will and for good luck: what it expresses is not so much the poet’s real agony and uncertainty as his function in hindsight – a poet struck by lightning will have become an antenna of sorts.

Neither quotation bothers to work out the effect on the poet of popularity and fame, but it seems easy enough: such a poet might not be inclined (in Jarrell) to go out in the wet so often, or (Swir) he might stop retuning his receiver, and stick to a familiar frequency. In the introduction to his 1988 selection of The Essential Wordsworth, Heaney seems uncomfortable, even compromised, as he discusses the starchy, establishment figure of the older Wordsworth, ‘in his large, not uncomplacent house’, seemingly ‘more an institution than an individual’, ‘an impression not inconsistent with the sonorous expatiations of his later poetry nor with the roll call of his offices and associations – friend of the aristocracy, Distributor of Stamps for Westmoreland, Poet Laureate’. In that padded, double-breasted construction, the double negative, Heaney would seek to offer criticism and mitigation at the same time, but in so doing he betrays his own anxiety.

I don’t know whether Glanmore, the house where Heaney wrote much of Field Work (1979), is large and complacent or not (although I doubt it), but readers of Seeing things learn that he has now returned to it as its owner-occupier, a condition which, with some more awkward double-speak, he celebrates in the seven sonnets of ‘Glanmore Revisited’ – in such lines as ‘only pure words and deeds secure the house.’ Of course, Heaney has also become the master of a ‘roll call of offices and associations’ of Wordsworthian distinction and dimensions, so it seems tempting to try on the ‘institution’ and the ‘sonorous expatiations’ for size as well. In the event, I don’t think they fit. The new book is many things, among them Heaney’s most plain-spoken and autobiographical work to date. It is a departure in style, tone and purpose. So nix institution and expatiations.

As much as any poet alive, Heaney has understood the need to move on, to remake himself from book to book. (In that same essay of his Jarrell quotes Cocteau’s advice to poets: learn what you can do, and then don’t do it.) Blake Morrison has drawn attention to the way Heaney likes to use the last poem of one book to suggest the nature of its successor, a pattern skilfully maintained over many books, beguiling his readers with a glimpse of the future. At the same time, though, in myself at any rate, each new Heaney book since Field Work has provoked an uncertain response. Either it was the poems that were slow to take, or I was slow to take to them – even such (now) obvious favourites as ‘The Underground’, ‘The Railway Children’ and ‘Alphabets’. In retrospect, this must have been because Heaney was always doing something slightly different – here was a popular poet who was (mercifully) less conservative than his readers.

Each of Heaney’s books since Field Work, at all events, has had a different concern and a different presiding genius. Station Island (1984) had its Sweeney poems and its Dantesque sequence of colloquies with ghosts (suggested by ‘Ugolino’ at the end of Field Work). The Haw Lantern (1987) had its allegories and parables, drily enthused by Eastern European poetry somehow filtered through Harvard and America. Seeing things is Heaney’s most ‘Irish’ book since North. While seeming to hark back to the whole of his career and to resume it – the seaboard and rustic settings and subjects, the translations from Dante and Virgil that frame it, the elegies for dead friends, the poems about driving and fishing (it is also Heaney’s most ‘sporty’ book) – it takes its note from the penultimate poem in The Haw Lantern, ‘The Disappearing Island’, and its last line: ‘All I believe that happened there was vision.’

The ‘unsayable light’ of an earlier poem (one of the original ‘Glanmore Sonnets’) is here said. ‘The rough, porous / language of touch’ that made Heaney famous is forsaken for what one might call the smooth slippery language of sight, the quickest and furthest, most abstract and disembodied, and most trusted and fallible of the senses. That sense of ‘words entering almost the sense of touch’, the deep historical familiarity for which Heaney strove earlier, has yielded to a kind of seeing that is half-dreaming. He takes up the cudgels against himself. He speaks quippingly of ‘the thwarted sense of touch’, and in ‘Fosterling’ writes:

I can’t remember never having known

The immanent hydraulics of a land

Of glar and glit and floods at dailigone.

My silting hope. My lowlands of the mind.

The equivalent in painting of the 48 12-line poems called ‘Squarings’ that make up the second part of the book would surely be abstracts called Impressions, Improvisations or Compositions, numbered like the poems.

The Haw Lantern was pioneering in that it had at its heart a single physical or geometrical image or schema, the hollow round or sphere which appears in a variety of guises: as the haws of the title; the ‘globe in the window’ of another possible title; the letter O ‘like a magnified and buoyant ovum’ in the touching first poem ‘Alphabets’, about reading and literacy and literature and read to the students of Harvard. There is the O of ‘Hailstones’:

I made a small hard ball

of burning water running from my hand ...

Then there are the many islands in the book, and there’s the sequence called ‘Clearances’ to the memory of his mother:

I thought of walking round and round a space

Utterly empty, utterly a source

Where the decked chestnut had lost its place

In our front hedge above the wallflowers.

The white chips jumped and jumped and skited high.

I heard the hatchet’s differentiated

Accurate cut, the crack, the sigh

And collapse of what luxuriated

Through the shocked tips and wreckage of it all.

Deep planted and long gone, my coeval

Chestnut from a jam jar in a hole,

Its heft and hush become a bright nowhere,

A soul ramifying and forever

Silent, beyond silence, listened for.

The O is both something and nothing, origin and omega, mother and rooted sense of self. Heaney consigns himself to living with its equivocations, in the fullness of absence. The haw is not a lantern, but he will live by its light, ‘its pecked-at ripeness that scans you, then moves on’. The round O’s in the book evoke maternity, self-sufficiency and the integrity of conscience: the one image brings to coherence Heaney’s personal loss in ‘Clearances’ and the several meditations on the practice of his art.

Seeing things has a similar geometrical leitmotiv or schema, and that is the straight line, or pattern of straight lines, dazzling as op art, and producing the sensation of depth. The lines are not adduced from such obvious sources as waves, layers of rock or clouds at sunset; they are rooted in experience and have more to do with a way of seeing, or even a way of being.

Here is the transcendence of Seeing things, the simple and miraculous escalation from a sixth sense to a seventh heaven, the lovely delusive optics of sawing and cycling and barred gates. The miraculous is produced by patience, by attentiveness, by repetition and work; there is no secret hinge the world swings on the way there is in Edwin Muir, a poet whose name has come up recently in Heaney’s essays. The lines – for once not ploughlines, not lines of verse – have their meaning, just as the sphere or circle of The Haw Lantern did. The meaning is not as intricate, or as deeply argued, as it was there, but here again it has to do with mortality, and with the generations of men. In 1986, Heaney’s father died, leaving the poet in the front line of the senior generation. The straight lines in Seeing things, the visionary buzz, seem to me to be connected to Heaney’s sense of the passing generations. The mower, the gate, the spinning-wheel, all have associations with death, as does the phenomenon of ‘lightening’, defined as ‘A phenomenal instant when the spirit flares / With pure exhilaration before death’. The book begins and ends with the descents to the underworld undertaken by Aeneas and Dante. At the same time, though, the dazzling, silvery lines are an epiphany, a standing vibration, and, for all their confusion, a stay against confusion and mortality. They are a paradox, the contemplation of something physical and at hand, giving rise to a long view of the human struggle, a metaphysics of light:

Heaviness of being. And poetry

Sluggish in the doldrums of what happens.

Me waiting until I was nearly fifty

To credit marvels. Like the tree clock of tin cans

The tinkers made. So long for air to brighten,

Time to be dazzled and the heart to lighten.

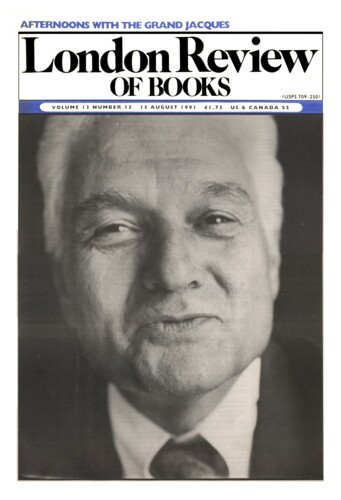

The straight line, the dazzle of abstract and op art, are the symbol and message – it seems an appropriate word – of the book, while its human content is drawn immediately from Heaney’s life. Experiences from childhood, his courtship and wedding, the death of his father and memories of him, the birth of his children, the painting of his portrait (the one by Edward Maguire that appears on the back of North), the acquisition of a bed, a house, the lapidary events of a life – and not a public life, or even necessarily a writing life: all are recounted and alchemised, worked into dazzle, overbrimming, ‘sheer pirouette’, ‘a dream of thaw’, the marvellous, ‘like some fabulous high-catcher / coming down without the ball’.

In the second section of the book, Heaney displays his new form, the 12-line poems made up of four tercets and known as ‘Squarings’. The 48 poems fall into four sections of 12, each one of 12 lines: squarings. He has perhaps found a compendious form for the work of his fifties, his version of Lowell’s unrhymed sonnets and Berryman’s Dream Songs. The poems are impressive for their freedom, their firmness of purpose, and their skilful arrangement – Berryman’s and Lowell’s forms retained, by contrast, the randomness of daily writing.

Naturally, not all of them are as good as the best ones – I would nominate v, xvii, xviii, xxviii, xxxiii and xlv – but there is nothing fuzzy about any of them, even the most mysterious. Their principle is the same transcendence as in the book as a whole: they are like homing devices, or Geiger counters, infallibly orientated towards the abiding surplus energy of the moments they describe. The aim is not to provide an adequate (and static) verbal icon, but to reflect in words some continuing effect, a vibration, a recurring figure, and this is how they end: ‘Above the resonating amphorae’, ‘In a boat the ground still falls and falls from under,’ ‘Another phrase dilating in new light’, ‘Sensitive to the millionth of a flicker’, and lastly: ‘That day I’ll be in step with what escaped me.’ These are more after-shocks than tied ribbons; they speak of the poems having located the source of the indestructible energy Heaney was after. Here, in full, is xxvii:

The ice was like a bottle. We lined up

Eager to re-enter the long slide

We were bringing to perfection, time after time

Running and readying and letting go

Into a sheerness that was its own reward:

A farewell to surefootedness, a pitch

Beyond our usual hold upon ourselves.

And what went on kept going, from grip to give,

The narrow milky way in the black ice,

The race up, the free passage and return –

It followed on itself like a ring of light

We knew we’d come through and kept sailing towards.

Here is the iterative motion, the abandon, the astrophysical in the playful, that characterises these poems. The adjacency of being and non-being. CERN in Geneva ought to like them.

Stylistically, Seeing things is plain as plain, sometimes ‘awful plain’ (Elizabeth Bishop, ‘The Moose’). The gutturals of early Heaney are long gone, and now also the suave Latinity – or Latin suavity – of what one can now call his mid-period. The poems have the most pedestrian beginnings, often stumbling over themselves, with humdrum idioms, and words repeated in the first lines, and rarely anything like a spark. An index of first lines would look dismaying. Occasional shafts of cleverness, against such a background, are almost wounding to the reader: ‘Like Gaul, the biretta was divided/Into three parts’ might look well on some poets, but one’s jaw drops on seeing it here. There are still the puns – more and more like tics – which now seem characteristic of Heaney, but which he may have got from Muldoon or Lowell. They are puns without the spice of puns, where the second meaning is only an amplification, an organ-stop, of the first, like ‘the free passage’ in the lines I’ve just quoted. Because of its preoccupation with dazzlement and with energy, language in Seeing things tends to be straightforward, unobstructive, building step by step towards its illuminations, without much in the way of decoration or distraction. One-word sentences and sentences without verbs abound, line-breaks can be so-so or worse, and, in going for clarity rather than elegance, he has even permitted himself several of those notably ugly adjective-preposition compounds that our parents and guardians always warned us against: ‘un-get-roundable weight’, ‘stony up-againstness’, ‘seeable-down-into water’. This wilful crudity and quiddity is evident in ‘Field of Vision’:

She was steadfast as the big window itself.

Her brow was clear as the chrome bits of the chair.

She never lamented once and she never

Carried a spare ounce of emotional weight.

In anyone but Heaney, and anywhere but here, this would be brutally demeaning, the person (twice) in terms of the thing, and then the vicious locution of the last line. I think it is the only passage in the book where pursuit of its dazzling philosophy has caused Heaney to be ruthless. As composed and constructed as his books always are – and as other people’s hardly ever are – and with a surprisingly thoroughgoing devotion to the insubstantial for a book with that title, Seeing things has taken Heaney to the edge of a new freedom, and to a set of poetic positions that are the very opposite of those with which he started out a generation ago.

Send Letters To:

The Editor

London Review of Books,

28 Little Russell Street

London, WC1A 2HN

letters@lrb.co.uk

Please include name, address, and a telephone number.