The rainy season arrived here on 27 October. As the first warm drops fell, the dusty ground gave out an unfamiliar odour, sweet, pungent and musty. Cars slithered on the slick roads, and soft dates, knocked from the palm-trees, made walking dangerous. Hassan, our driver, turned up in a black suit with stripes like railway lines, to mark the end of summer. It clashed badly with his plastic sandals and his brown tie. I looked out of my hotel window and watched the rain with a certain frisson: I remembered being told by a leading Palestinian figure that Saddam Hussein had forecast that an attack by the Americans would come soon after the first rains.

Yevgeniy Primakov, President Gorbachev’s special negotiator, also arrived in Baghdad on 27 October. It seemed the best hope for a negotiated settlement, and the Russians and the French, who were co-operating on the diplomatic effort (though only in private), were in optimistic mood. The British and American Embassies were sceptical, and they were right. President Saddam Hussein and Mr Primakov were together for only forty minutes, half of which was sacrificed to translation. Nothing was agreed, and the President refused to entertain the notion of an Iraqi withdrawal from Kuwait. The following morning Mr Primakov, his jolly proletarian bounce temporarily deserting him, left Baghdad Airport. He had no plans to return. The talk in the British and American Embassies was of war by the fourth week in November. I found myself looking out of the window again.

From the television screen there came a blare of trumpets. A man on a magnificent white stallion was parading across a huge open area, applauded by thousands: the Saladdin of kitsch. The shot changed, and small children held up portraits of him: the schoolboy, the young revolutionary, the prisoner, the apparatchik, the power behind the throne, the strong man, the President – a life of Saddam Hussein in pictures. The television cut to studio. A singer with a glittery tie and a suit with a python-skin pattern broke into a song with Bedouin words and music:

All evil people fear your sword, Saddam.

It has already been tested.

You are the father of all good things.

With you we will challenge

All the aggressors who have accumulated

Wealth and strength and power.

There was a swift change of key; the python-clad arms were raised in prayer.

We implore God to keep you well and happy,

To make your countenance shine on us,

So we can take pride in you above all others.

The python pattern faded. We were left with a still photograph of date palms at sunset. ‘Here’s to you, Mrs Robinson’ was played by violins. It was time for the News. President Saddam Hussein would feature heavily in that, too.

This is landscape I have explored before. Romanian Television used to call Nicolae Ceausescu ‘our bright morning star’ and ‘our avatar’. On one marvellous occasion the Romanian media referred to him as ‘our Prince Charming’. Pictures of him, preternaturally young, were waved in unison in front of platforms where his current 70-year old self, the black hair turned white and the face turned wrinkled, was appearing in person. The news was his news: if Ceausescu visited a chicken farm, it took precedence over everything else. On the day of the Armenian earthquake Romanian Television led on a response from President Houphouet-Boigny of the Ivory Coast to a message of congratulations from Our Prince Charming. Ceausescu’s thoughts, displayed by the roadside, beguiled every journey. The official religion of Romania was egoworship.

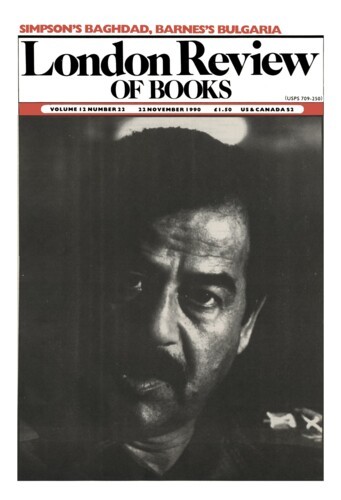

Here in Iraq, however, there is a more particular purpose behind the ten-fool posters of the smiling Saddam, the television eulogies, the photograph on the front page of every newspaper. At an Arab summit, seven years ago, a journalist, greatly daring, asked why he was building up a cult of personality. It was brave, because although it is acceptable to establish such a cult, it is not acceptable to admit that one exists. Saddam’s response was, as it happens, mild enough, ‘It’s just that I’m becoming a symbol for the Iraqi people,’ he said. There is something in that. The portraits which dominate crossroads and major buildings throughout the country are there in part to express his domination over the cultural and ethnic diversity of Iraq. In them, like a visitor to a theatrical costumier’s, he appears in the Bedouin k’fieh, the turban of a Kurd, the suit of an urban businessman. He is the embodiment of this entire fissiparous nation. The Ba’ath Party’s propagandists berate the British for the artificial creation of their country’s borders, cutting Kuwait off from Iraq and separating out a corner of the Ottoman Empire with no regard for cultural or demographic boundaries: and yet Saddam, the head of the Ba’ath Party, defends this artificial entity with great ferocity. With its Arabs, Kurds and Assyrians, its Shia and Sunni Muslims, its three or more types of Christian, Iraq can survive only if it is kept together by main strength. Left to itself, it would fly off into twenty or more pieces, a Lebanon on a big scale. The Ba’athists have spoken for 48 years of the need for a leadership symbol. Nowadays Iraq has a leadership symbol, with a vengeance.

It is very hard to make people here talk about Saddam Hussein himself, even in the privacy of their homes. ‘There is no one I can be absolutely certain is trustworthy,’ said an attractive, tall woman of Kurdish origin. She indicated with her forehead a group of women of her own age who were standing talking a little way away. ‘They are all my friends, but I never say anything political to them. They don’t want to hear it, and I don’t want to take the risk. I know that they don’t like what happens here, but it’s not safe to say so.’ After the end of the Gulf War in 1988, when there was considerable discussion of the political future of Iraq and ideas for a new, and perhaps more liberal, constitution were being aired, the Foreign Minister, Tariq Aziz, told the other members of the Revolutionary Command Council that Iraq required a leader who was feared: otherwise, he said, it would be ungovernable. Aziz is, or was brought up as, a Christian, but he quoted a Muslim saying: a leader who isn’t feared is like an Imam who can’t discipline his congregation.

And yet at some level of consciousness even those who dislike the system and fear it tend to give it tacit support. This is a turbulent country. Anyone who was weaker or more tolerant of dissent than Saddam might allow things to slip back as they once were, when any ambitious army officer could entertain hopes of political power. Iraq suffered its first military coup in 1932, and there have been plenty since then. ‘Gone are the days,’ said Saddam Hussein, early in his Presidency, ‘when a captain could ride his tank to the Presidential palace and storm it.’ Saddam’s control system, based on his personal supervision of the Army, the security organs, and the Ba’ath Party, is a fierce insurance against chaos. During the war with Iran Saddam showed where his priorities lay by ordering that no tank should be equipped with a radio set. It made them less effective at fighting the Iranians, but it ensured that they couldn’t be turned round by some ambitious captain and driven to the palace.

It was the Gulf War which established Saddam’s Iraq in its present form. The invasion of Iran was conceived as a knockout blow against a troublesome adversary which was going through a period of revolution and political weakness. Directly it became clear that Iran wouldn’t be a push-over, and that Iraq stood a strong chance of losing, Saddam Hussein’s own position became more questionable. In 1982, when the fortunes of war strongly favoured Iran, Ayatollah Khomeini accused him of being an unelected tyrant and challenged him to stand for election. By comparison with Iraq, the Islamic Republic of Iran has always been, in its distorted way, a kind of democracy: so it wasn’t altogether grotesque for Khomeini to criticise Iraq on these grounds. Saddam’s response was characteristic: the accusation worried him, but instead of submitting himself to an election he organised, Eastern Europe-style, a Day of Allegiance. On 11 November 1982 13 million people – and for once this was probably not an absurd overstatement by the Iraqi media – came out onto the streets in corroboration of Saddam’s claim to have overwhelming popular support. It was a very Ceausescu way out of an awkward situation. Soon afterwards the poetry readings about Saddam began on television, and the portraits began to appear on every street corner.

One wing of the Saddam Arts Centre, an uninspired place where exhibitions of painting and obedient political posters are held, is devoted to photographs of the leader. There must be four thousand of them, dating back to the wide-lapel and fat-tie days of the late Seventies. Scarcely anyone seems to visit the exhibition, but one of Saddam Hussein’s personal photographers, a gloomy figure with a thin moustache and an expensive silvery suit like a Big Band leader, toured the echoing rooms. He would stop approvingly every now and then when I spoke to him, praising his leader’s humanity or his courage. That was several months ago. When I went back recently, this part of the exhibition hall was empty and the gloomy photographer had gone. In the early days of the crisis over Kuwait (the authority for this is Yasser Arafat, who has a house here and spent much of his time with Saddam after the invasion), the President thought the Americans would launch a nuclear attack on Baghdad; perhaps it was what he would have done in the circumstances. The artistic treasures of the city were packed up and slipped out for safety. The Assyrian bulls and Akkadian crown jewels went, and so did the four thousand photographs of Saddam Hussein.

Each day’s newspapers here are obliged to carry a prominent picture of Saddam. He selects them himself, according to the photographer. All the major statements of policy are drafted by him, and bear his complex and challenging patterns of expression. He has no one to give him advice, and doesn’t want any. President Ozal of Turkey said early on in the present crisis that the hardest thing about dealing with Saddam was that he had no advisers. He is commander-in-chief, secretary-general of the Ba’ath Party, chairman of the Revolutionary Command Council. He is the State. The RCC, the supreme ruling body of Iraq, used to have 12 members. Now there are six. The others have died, been gaoled or disgraced, or have simply disappeared. You do not retire from high office in Saddam’s Iraq. Tacitus wrote of the closest associates of the Emperor Gaius: proximis saevi ingruunt. Being close to a man like that can cost you your life. The more you know, the more you are likely to suffer.

And yet the comparisons with Hitler and Stalin, which are so easily made, have little serious relevance. Saddam is his own man, not a reincarnation. His style of rule means that Iraq is Saddam: its negotiating strengths, its weaknesses, its judgments – faulty or accurate – its future, its fate, are all his; and he has the mind-processes of a conspirator. The smiling friendly features belie the small obsidian eyes: you would never know where you stood in those eyes, never know at what level the things that were being said received the inner assent of the mind from which they originated.

The fiercest of us have our vanities, however. No one who allows himself to be shown nightly on television in flowing robes, mounted on a white stallion, can be devoid of self-regard, or indeed of self-romance. He isn’t a figure of absurdity, like Ceausescu, and he doesn’t have Ceausescu’s pomposity nor his courtiers and flatterers. His habits of life, moving round from palace to safe-house on a nightly basis, ensure a certain austerity. But, like Ceausescu, he is building a monument to himself which is intensely self-revealing. There is a good deal of official sensitivity about it. ‘You must not say this,’ said the television censor, after viewing one of my pieces. ‘I understand English very good, and when you say “President’s palace” you try to say it belongs only to him. You must say “Presidential palace”, because it belongs to all Iraq.’

Ceausescu’s officials used to say the same thing about the House of the Republic in Bucharest. Saddam visits the Presidential palace with great frequency, and takes a penetrating interest in its construction; in a recent period of ten days, at a high point in the Gulf crisis, he paid three long visits to the palace, giving the same attention Ceausescu devoted to the House of the Republic in his final months in office, with the same obsessive regard for quality and the same disregard of cost.

You can see the two domes of the palace from my hotel room: one amosque-like blue, the other copper. Originally the copper dome was to have been of glass. It covers a water-garden the size of a football pitch, with fountains operated by computer. Early this year, Saddam came to look the project over, and found it insufficiently grand. It was redesigned at a cost of tens of millions of dollars. The floors in the main palace were to have been carpeted, but when the President saw the carpets he took a dislike to them. The floors, he decided, should be of inlaid marble instead. The carpets were abandoned in one of the three barracks which will house the President’s praetorians. The furniture, the fixings, the gadgets, the chandeliers, the electronics which Saddam rejects are all dumped there. It is like a three-floor department store inside.

As for the palace itself, the suites are all in teak (except for the President’s, which is in oak). His four-poster bed is hydraulically-operated; his bathroom has gold taps, gold showers, gold tiles. The great chandelier which hangs from the blue dome is 20 feet high and 12 feet across, and the electric bulbs in it give off three kilowatts of heat. It is said to have taken four years to put the 80-millimetre glass into the great windows. The glass is laminated, and is thick enough to withstand not just a bullet but a rocket or a small missile. Each layer baffles the attempt to break through, in something of the fashion of the President’s own mind, laminated at the various levels of consciousness against outside penetration.

Looking out across the haze of Baghdad at the blue dome and the copper dome, I find it impossible not to wonder what – if the hawkish diplomats in the British and American Embassies are right – it will all look like in a month or so. Ceausescu’s house was within two months of completion when he was over-thrown. When will Saddam Hussein operate his hydraulic bed, or switch on his golden shower?

Send Letters To:

The Editor

London Review of Books,

28 Little Russell Street

London, WC1A 2HN

letters@lrb.co.uk

Please include name, address, and a telephone number.