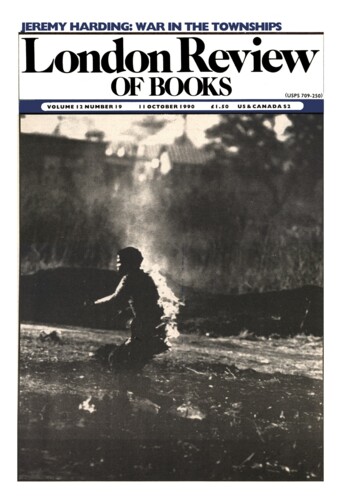

Last month, two days after the war on the Reef between Inkatha and the ANC erupted in Soweto, the families in Klipspruit Extension were moving out. The windows had been smashed in every single house on the dusty road through this respectable, middle-class development. Dozens of well-dressed middle-class Sowetans were loading mattresses, tables, cushions, chairs and pictures onto pick-up trucks and roof racks. There was a house set back from the road, fronting the open field through which Inkatha must have come. It belonged to the Kunene family, one of whom had recently died in a car crash. When Inkatha burst in, the family were holding a vigil for the dead man. The women must have been in the covered yard at the back preparing food for the funeral the next day. The big pots had been overturned and there was a litter of freshly-sliced vegetables on the floor. The rest of the makeshift outdoor kitchen had been broken up, its contents strewn on top of the vegetables – except for the meat, which had been stolen. All that remained of that, propped on the surface of a listing wooden table, was an enormous cow’s head, its horns angled up to the canopy and its dim eyes fixed on the dirt path at the back of the house.

At the front entrance, there was a wash of blood across the white cement wall and two dark patches in the rectangle of grass beyond. The dead man’s father-in-law and a close friend of his had both been killed in the attack. A third corpse was found some way from the house. The victims were said to have died from stab wounds. The other mourners had been forced to abandon the coffin and the body of the man they were supposed to bury. Walking back through Klipspruit into a nearby squatter camp, where the residents were singing freedom songs and calling for Inkatha blood, you could see that the past would take a long time to lay to rest.

As for the future, it is obscured by violence almost everywhere one chooses to look. There is the war in Natal, still sputtering on, between Zulus, mainly urban, who declare for the ANC and those, mainly rural, who support Chief Mangosuthu Buthelezi and Inkatha. This difference of opinion has already cost nearly four thousand lives. Then there is the latest war on the Reef – the one we are reading about – of which the conflict in Natal was the precursor. In the Reef, however, it is mostly Xhosa blood that flows through the veins of the Congress and so the killing has an ethnic character. Two mighty hosts of tribal sentiment (Xhosa and Zulu) are being raised for yet another war, should the current ones happen to abate. There are also several varieties of Afrikaner jihad which it would require a stable centre to head off.

In August the statisticians announced that the per diem death rate in the Transvaal had surpassed even that of Beirut (in 1988 the same kind of chastening comparisons were made for Pietermaritzburg in Natal). It is depressing that the Reef war should have featured on the Beirut Index, and depressing to read about it in the Daily Mail, ‘the paper for a changing South Africa’. South Africa is changing all right: the violence is intensifying, the rhetoric is darkening, flexible positions are suddenly hardening again and the poor, whose material situation must be vastly improved for any political settlement to work, are worse-off as a result of the country’s steady economic decline. (Negative growth of approximately 1.5 per cent is reported for the first six months of this year.) It is an ominous sign, too, that the Daily Mail has since collapsed. Not so little things like this, and epic horrors like the township war, combine to persuade even modest optimists that their hopes have been ill-founded.

Since the outbreak of the war on the Reef, it has become a national addiction to scour the papers for news of whether Buthelezi and Mandela will meet and draw a halt to the killing. Twenty-four hours after the Klipspruit attack (a minor episode in an escalating nightmare), the papers could offer no solace on this question. In Johannesburg, however, the Star dedicated half a page to the artistic talents of South African celebrities: doodles for charity. The two most prominent contributors were the Deputy President of the ANC and Winnie Mandela – Nomzamo, ‘the one who strives’.

The drawing by Mrs Mandela showed two chained hands, the fingers pointing downwards and their nails dripping blood. It was bleak, violent, crudely rhetorical – not unlike her many public pronouncements since the famous necklace dictum of 1986. In a speech given in Soweto two days earlier, she had pushed the accusation that the Police were collaborating with Inkatha against the ANC to the kind of conclusion that infects South African politics: The Police is Inkatha. She went on: ‘The question by youths is why not suspend talks with the Government and continue with the armed struggle?’ Even at that time, a more pressing question for hundreds of Sowetan youths was whether Mrs Mandela would face charges in connection with the murder of Stompie Moeketsi.

The drawing by Nelson Mandela was a beautiful thing. There were four elements separated in space but linked, one supposed, in the mind of the doodler: a rabbit on its haunches, a woman, a giraffe and a mysterious object – perhaps a carved wooden stool or headrest – resembling a newspaper laid on a trestle. The little picture had an openness of heart quite foreign to the pursuit of power. Unlike Nomzamo’s, which might as well have been the emblem of her football club, it said nothing obvious or apposite about the state of the nation. If anything, the Sunday-morning reader scrutinising it for some helpful clue would have gone away with the ominous sense that a leader was doodling while the townships burned.

Perhaps he was, or perhaps that is merely another South African conclusion. Since the great opening in February, the conflict between the state and the South African majority has been melting into a slush of small wars, feuds and skirmishes – always present but now more clearly discernible – in which it is hard for leaders to stay on their feet. Chief Buthelezi is widely believed by supporters of the ANC to be fighting his way to the negotiating table (he is and so did the ANC); he is hated for his ambiguous relation to the old order and blamed for the killing in the Reef, no matter how it may have started. This makes him a dangerous man for Mandela to talk to. Buthelezi is the enemy: but Mandela has already made crucial concessions to ‘the enemy’ – a different one but the two are quickly conflated – above all, by suspending the armed struggle. This move was greeted with great dismay by many people in Soweto and their worst suspicions were confirmed when Inkatha started raising dust in the Transvaal. If a meeting with Buthelezi now seems inevitable, it was not obvious at first whether Mandela could go straight to the source of the trouble without a major outcry from his anguished supporters.

The ANC may be wary of talking to Inkatha but its reluctance to do some hard talking within its own ranks is more alarming. There are no working channels of communication between the leadership, fresh out of jail or back from exile, and the mass movement, which has local figureheads of its own. Such links need to be forged very fast. Real thinking has simultaneously to take place at street level in the townships, where hours are passed in interminable singing, re-arranging of chairs and points of procedure – less popular with the ANC’s well-organised rivals, the Pan Africanist Congress – when they could be spent trying to revive, and improve upon, the local structures eroded in the repression of the mid-Eighties. Without such basic groundwork, there can be no disciplined movement and no direction for the political talent now being squandered in the townships.

This, however, is to look beyond the current conflict with Inkatha to some rapid resolution, of which there is no guarantee. The rise of a coherent, disciplined movement is also difficult because of the swamp of violence on which it must be built. In South Africa last year there was a murder every 45 minutes, a rape every 26 and a serious assault every four. By the start of 1990, police were resigning from the force at a rate of 22 a day – the pay was pitiful (it has since come under review) and the risks were high (they have been dying on the job at a rate of roughly sixty a year since the mid-Eighties). The Police are roundly criticised for incompetence and indifference when it comes to common crime; in periods of unrest they are seen as the agents of oppression, which is the case now in the Reef.

Soweto, meanwhile, is steeped in crime: not just the ordinary violence which fills the casualty unit at Baragwanath Hospital every weekend with a stream of people who have been beaten, stabbed, shot or burned in run-of-the-mill incidents, but semi-organised gangsterism. Before the war with Inkatha came to the township in August, a gang called the Jackrollers was plying the streets, dabbling in car theft but specialising in the abduction of young girls at gunpoint. They would hold up a car, sometimes a crowded minibus, and haul out whoever took their fancy. Some of the girls were held for a night, some for a week, some never reappeared. The Jackrollers were also going into schools and removing girls from classrooms. In one incident the gang ‘jackrolled’ a bride while the newly-weds were heading off on their honeymoon. The Jackrollers and two other violent gangs, Ama-Japan and the Ninjas, have fought street battles of their own when they were not busy terrorising residents.

It was the Comrades – young men now patrolling the war-torn streets of Soweto in self-styled citizen’s defence units – who took on the Jackrollers in June and July. Three big Jackrollers were killed in those months and shortly afterwards a vigil for one of the dead men was attacked by the Comrades with an AK47 and a shotgun. The avengers were probably South African Youth Congress members, the ‘young lions’ of the ANC, as Mandela calls them, who felt that the Police were doing nothing to bring in the gang.

This kind of action represents another huge problem, not only for the ANC, but for the townships in general. The long absence of law and order except as an instrument of repression has given the kind of habits to young people that will not sit well with party discipline. Until there is proper policing, residents will have to choose between rule imposed by the Comrades and rule imposed by the gangs; or merely a sporadic war between the two, in which it is no longer clear to most people who is who. If the Comrades are a preferable option in many ways, there is no guarantee that they will remain so. Comrades come in many different guises and the residents of Orlando West have seen what can happen when a powerful figure in the struggle decides to dispense justice through a football club.

This year a new gang began to operate in Soweto. They were known as AK47s, because they were armed with assault rifles, and they were said to be more than normally trigger-happy. In July I met a man in Orlando East called Tiger, probably a petty criminal in his own right, who had been attacked by the gang. They had burst into his house while the family were watching TV and opened fire. Tiger had survived the attack but could not answer questions about the incident. He could only say that Soweto was now full of ‘Mozambicans with AKs’ – the third time I had heard this rumour. Did Tiger think AK47s were former members of Renamo, the right-wing anti-government insurgency in Mozambique run by South Africa during the Eighties? He didn’t know and nor did any other resident I met.

No one can agree whether there is, as many say, a hidden hand in the Reef war or whose it might be. De Klerk has hinted at extremist elements in the streets who want to sabotage negotiations; Mandela has begun to blame the state. It would be a relief to think that it was a band of ex-Renamo, working alongside Inkatha hit squads, directed by elements in the security forces. But there is no proof of this. Some Zulu hostel-dwellers claim that they have been forced to join Inkatha and carry out attacks on township residents, and even that the Police have based themselves in hostels, orchestrating raids against the Comrades after dark. This may well be true; there is certainly long-standing hostility between the Police and the residents in Soweto and at least once in the last few weeks I have seen the Police work it up into crude battle. This kind of hand, laden with bad intentions, is no more hidden than the hands in Winnie’s doodle.

Last month in the township of Kagiso I went inside a Zulu hostel. It was a dismal place, an all-male barracks patrolled by a company of Inkatha warriors in red headbands, carrying a great array of weapons. About thirty people had already died in Kagiso. Six hundred yards away an army of township residents had come to a halt in front of a police line which was there to stop them marching on the hostel. The rectangular yard at the centre of the hostel sported a couple of parched trees, several dismantled cars and an elderly dog confined in a kennel of rusting bedsprings. A few of the inmates were sitting in front of their quarters smoking grass.

Joshua Ndaba was a spokesman for the hostel, an Inkatha man; he had been there 18 years, working in a nearby chemical plant. Ndaba said he stood against ‘violence, sanctions, all the things that are out of order’. In short, he stood against the ANC. He would not admit to being scared of the township residents – ‘the Xhosa nation’, as he called them – but there was fear in his eyes. And there was relief in the faces of the two young residents to whom we gave a lift on the way out. I told them we had just come from the hostel. They said it was a frightening place. ‘You’re terrified of Inkatha and they are terrified of you’, one of us ventured. ‘So how will it end?’ The younger of the two thought for a moment. ‘We burn down the hostel,’ he said, ‘and everything will be all right.’

Faith in simple solutions is all too easily acquired amid the suffering and confusion of township life. In Soweto particularly, the shadow of violence is now as substantial as the deprivation which casts it, and things have become hard to tell apart. Long before this war began, Soweto had become a world of hidden forces – of crime lurking behind politics, of wrong discreetly chaperoning right, of rivalry dressed up as solidarity, of wars for freedom concealing wars for turf. Soweto is on the whole a desperate place, frozen into a poverty we can no longer conceive. Very many, and mostly the worst, effects of the 20th century have filtered through the semi-darkness, but the real time of the township is mid-19th-century industrial England: the England of Engels and Henry Mayhew. It is in this awful space, and others like it, that the war between Inkatha and the Comrades carries on. Until the space itself begins to change, there will be no end of recruits for no end of wars.

Send Letters To:

The Editor

London Review of Books,

28 Little Russell Street

London, WC1A 2HN

letters@lrb.co.uk

Please include name, address, and a telephone number.