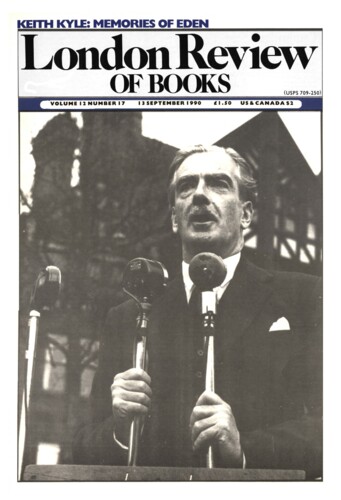

Anthony Eden should be living at this hour. He would hear the President of the United States say: ‘Half a century ago the world had the chance to stop a ruthless aggressor and missed it. I pledge to you we will not make that mistake again.’ He would see the United States, uninhibited as she apparently was in 1956 by the separation of powers and the prerogatives of Congress, move with sureness and speed to confront a dictator in the Middle East. He would think that, as he had always predicted, the United States, when faced, to use his words, with ‘what is in fact an act of force which, if it is not resisted, if it is not checked, will lead to others’, had at last come round to his way of thinking. And, having indulged himself for a while with the thought that when the chips were down he would be able to count on Hugh Gaitskell, only to be sadly disappointed, he would note, with a tinge of envy, the degree of political support enjoyed by Margaret Thatcher, with Neil Kinnock and Gerald Kaufman endorsing her every move.

In normal times issues of international law are seen as a recondite speciality: in moments of stress they turn out to be of crucial importance. In 1956 the British knew from the very beginning that they had a weak legal case against Nasser; and this profoundly affected their handling of the Suez crisis. The President of Egypt had nationalised the Universal Suez Canal Company without notice, by a mechanism akin to a military coup. In law it was an Egyptian company, in which the British Government was the largest shareholder and most of the private shareholders were French. The shareholders were told that they would be fully compensated and the non-Egyptian staff (whose co-operation was thought by themselves and many others to be indispensable to the smooth working of the canal) were told that if they did not stay on the job they would be sent to prison. This threat to make hostages of the captain-pilots and land staff was immediately identified by the American President, among others, as the one weak aspect in the Egyptian posture. It was speedily rectified.

The day after Nasser’s ‘grab’, as the Daily Mirror called it, the Cabinet minutes record ministers as saying that, ‘from the strictly legal point of view, his actions amounted to no more than a decision to buy out the shareholders.’ Given this, it is not surprising to find among Eden’s private papers the following note scribbled to the Prime Minister a week later by the Cabinet’s leading legal luminary, Lord Kilmuir, the Lord Chancellor: ‘For Gawd’s sake don’t let us get tied up in “legal” quibbles, thus entailing delay. Hit him on the nose – and hit him quick before he gets his pals around him!! Forgive my frankness but I do know the breed pretty well still!’ Partly for such reasons, partly because of the near-certainty of a Russian veto, Eden’s view in the early part of the crisis was best expressed in a comment scrawled on one of his papers: ‘Please let us keep quiet about the United Nations.’

Different sets of facts led to a very different attitude being displayed both in the Falklands crisis and in the current confrontation over Kuwait. On both of these occasions, a nation advanced over the borders of another and was told by the Security Council to withdraw; on both occasions, the applicability of Article 51, which permits the use of force in individual or collective self-defence until the Security Council has taken appropriate action, was generally recognised. In the case of the Falklands the United States then made available to Britain that diplomatic, logistical and intelligence support which the Joint Chiefs of Staff had advised President Eisenhower to supply in 1956. Eisenhower, being a victorious general, saw no need to accept that political advice.

The invasion of Kuwait provides the first occasion on which the UN has been asked to work in a post-Cold War environment. This, it has been pointed out, is the way it was always supposed to work but was never given the chance to. It will not, however, be given an entirely clean sheet and enabled to start again as if we were still in 1945. For one thing, some Third World countries, and notably Iraq, have acquired a military and technological capacity that reduces the overwhelming superiority of the permanent members of the Security Council which was supposed to keep them in order. For another, it will not be an easy thing to erase from many minds the memory of past failures and unfairnesses, not all of them directly attributable to the polarisation of the Cold War, not all of them anti-Arab in impact.

When the Iran-Iraq war began with Iraqi aggression against Iran (not unprovoked aggression, it is true, but it is the recourse to force itself which the UN Charter is concerned to ban), the two superpowers were jointly and severally too embarrassed and inhibited to take an effective position on the restoration of peace. It was an awkward case of two exceedingly unpleasant regimes doing each other damage; there was no immediate threat of World War Three; no great urgency about upholding the principle of peace; and because of the unholy dread of the ayatollahs which was jointly entertained in Washington and Moscow, an inclination to lean on the side of the aggressor whenever there was any prospect that Iran might win the war. We are now paying the price of containing Khomeini; and Iran’s ‘impossibilist’ demand that Saddam Hussein be destroyed is echoed in many American political speeches. In Britain, the Observer, which had famously denounced the ‘crookedness’ of Anthony Eden just as our men were going into battle, came out with a headline identifying Saddam with Hitler.

Everyone can nurse his own double standards, but, as in domestic law, this must not be taken to mean that we should have no standards at all. And the resolution of the Cold War is not of itself going to make the development of objective standards much easier. Anyone who applauds the sterling way in which President Turgut Ozal of Turkey embraced his country’s front-line and very costly responsibilities under the UN sanctions against Iraq can see that it will be doubly hard in future to impose effective pressure on Turkey over the question of Cyprus. The big losers are liable to be the Palestinians, however, who must reflect that the 1949 Geneva Conventions, which are the basis of our case against the taking of hostages and specifically against moving them near vulnerable military targets, are precisely the ones which the Israelis violate every day in the occupied territories: the Conventions do not permit the dynamiting of houses, the dilution of population by settlements, or the removal of detainees from the territories.

One respect in which the events of 1990 have mirrored those of 1956 has been the initial eagerness of all parties to keep Israel right out of sight. There were some individuals who favoured Israeli involvement in the Suez conflict from the start: most prominently on the British side, Harold Macmillan (though Macmillan only really wanted the Israelis to ‘make faces’ so as to distract Nasser’s attention) and, outside government but still having access, Winston Churchill, and on the French side the Foreign Minister Christian Pineau. Eden’s stand was peremptory, however: no Israelis. The message reached Ben-Gurion by way of the French and was at first not unwelcome. Now Yitzhak Shamir has given out the word that the Gulf is a long way away and that Israel is not directly concerned. If Israel is on one side, all the Arabs will line up on the other. The Iraqi leader in 1956, Nuri es-Said, was a friend of Britain’s (though, Israel hissed, no friend of Israel’s: if Iraqi troops moved into Jordan it would mean war) and an opponent of Nasser’s. His advice to Eden on the nationalisation of the Canal was roughly the same as the Lord Chancellor’s and given in much the same language. Eden would have Arab support against Nasser, provided only that he did not get mixed up with the Israelis.

It has been the Israeli contention for a great many years that Europe and the United States are basically mistaken in their assessment of the centrality of the Palestine problem to the stability of the Middle East. Arabs talk a great deal about Palestine, the Israelis say, but in practice many other regional interests have a greater priority. The extent of Saddam Hussein’s betrayal of the Arab cause is shown by the fact that he has not once but twice acted to vindicate that thesis. The attack on Iran was such a failure that he had to be helped, despite himself, by the ‘Arab nation’ to avoid the unthinkable consequences of defeat. He then fought a successful but immensely costly defensive war, the fruits of which he has now coolly surrendered to Iran to clear the decks for his new adventure.

Iraq’s present contribution to Arab solidarity has been to wipe the Intifada from the headlines (indeed from news reports almost entirely) as well as driving a wedge between the Israeli peace wing and the Palestinians in the very year that was to be devoted to winning over fresh segments of Israeli opinion. This has enabled the right-wing coalition in Jerusalem to give would-be plausibility to the idea that a future Palestine state would become another Iraq. In 1956 the British placed much reliance on the ‘psy-war’ against Nasser. To the irritation of some Israelis, especially Golda Meir, the several ‘black radio’ channels at work sought repeatedly to discredit Nasser by suggesting that he was assisting the Zionist cause. One wonders how long it will be before the same is being said about Saddam Hussein.

It is impressive how many Arabs Saddam Hussein has alienated and (which is not the same thing, as the example of Nasser makes clear) how open they are about it. The potential for embarrassment in the West – among, for example, the Opposition parties in Britain and for American opinion generally – at being committed to the restoration of the Al-Sabah Emir and all the other members of the Al-Sabah clan is more than made up by the conspicuous refusal of even a single known member of the very lively Kuwaiti Opposition to identify himself with the invasion. In Egypt Hosni Mubarak, after nine years in office, has at last found genuine popularity as an effective leader of the Arab League in condemnation of Iraq. Some Syrians, it is true, are finding President Assad’s pro-American U-turn too abrupt. But mainly it is the Palestinians who, embittered at the feebleness of the world community on their behalf, now find themselves tragically on the side of an occupying power.

What all these crises have in common, however different they are in all sorts of other ways, is that they pose to the political leadership the tough test of matching the diplomatic with the military timetable. In all three cases, ‘hot reaction’ to the affront was not feasible. The military machine needs time – in the case of Suez six weeks – to get into place. Then as now the interval could be filled with politics and diplomacy, but at the end of it everyone should in theory be prepared for buttons to be pushed and the military sequence to begin. With a principal ally in the United States who did not want to use force anyway, Eden lost control over the timetable – a thing Mrs Thatcher, faced with dangers of a similar mismatch, avoided over the Falklands.

George Bush has many advantages over both of them, but he will face variations on the same basic question. While his forces are building up in the Gulf there can be time for long closed sessions of the Security Council. Once they are all in place (on Saudi or other bases – a luxury Eden never had), the same question will arise which tormented Eden: will Saddam Hussein be obliging enough to supply a casus belli? The Americans and their allies have enough support from the UN to act in imposing sanctions. But will sanctions, in these almost ideal conditions, work or work quickly enough for the troops sweating it out in the Saudi sand? Admiral Barjot, the French Deputy Commander-in-Chief of the Suez expedition, was confident that Nasser was mad enough to try a Pearl Harbour against Malta or Cyprus. The British did not really agree with him on that, but thought that either Nasser’s nerve would break so that he would interfere with British and French ships refusing to pay Canal tolls to the Egyptians, or that his faith in the Egyptians’ ability to run the Canal without experienced foreign staff would prove unfounded. Neither happened; Eden’s nerve broke and he violated his own first rule: never in the Middle East end up on the same side as the Israelis.

In America there are many voices – Henry Kissinger, Richard Perle, Congressman Les Aspin, among many others – who are today demanding openly what Eden, in the case of Nasser, and his colleagues could only resolve in most secret conclave: the destruction of Saddam Hussein, the old war aim of Khomeini, and the smashing of his nuclear potential before it is too late. Saddam Hussein may simply decide to wait the Americans out. That basically was Nasser’s tactic. Or he might really decide to live or die an Arab hero by taking over Jordan, confronting the Israelis, and asking the ‘Arab nation’ where it stands or whether it exists.

Send Letters To:

The Editor

London Review of Books,

28 Little Russell Street

London, WC1A 2HN

letters@lrb.co.uk

Please include name, address, and a telephone number.