Romania’s attempt to establish democracy lasted almost exactly six months. After the December revolution, Romanians did begin to use their new passports to travel abroad, they were able to buy and sell goods for the most part without fear of reprisals from the state, and for the first time in over forty years, they could freely speak their mind.

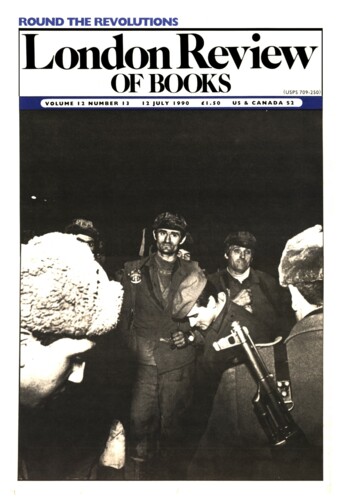

That all came to an end on 14 June with the arrival in Bucharest of the twenty thousand shock troops of the Iliescu regime, the miners from the Jiu Valley. This is the third time since the revolution that they have made the trip to the capital, and on each occasion they have demonstrated their fierce loyalty to the National Salvation Front. But this was the most brutal of their visits. For over thirty-six hours they rampaged all over Bucharest beating up anyone who crossed their path. They were extremely savage. Some broke into a secondary school. They beat the children, on the grounds that one 16-year-old had spoken to anti-government protesters in University Square. The beating was only stopped when the teachers gathered their courage and formed a barricade around the school. This was one incident among thousands.

The street in which I live is a quiet one in a leafy suburb of the old city, a mile or so from the centre of town. Three houses down from mine is a district office of the opposition National Peasants’ Party. During the election campaign I dropped in there two or three times to try and find the local candidate. There were only ever a few people in the building and they never knew the whereabouts of their prospective representative. It was an obscure and unimportant party office in which very little hard organisational work was done. But the miners found it and destroyed its contents. I cannot believe that they chanced upon the building: they must have been told where it was. Indeed, it’s becoming increasingly clear that some of the more thuggish of the National Salvation Front’s bosses were working closely with the miners’ union leaders throughout their stay in Bucharest.

Whatever else the Ceausescu regime may have been responsible for, it did not resort to open violence on this scale. Using the miners to suppress the opposition was a tactic original to the new regime and had fascistic elements. The miners’ racism became evident when they made a particular target of Gypsy markets and the area of Bucharest in which most Gypsies live. The Gypsies can be forgiven for recalling that similar treatment was meted out to them by Hitler’s henchmen, who went on to incarcerate the Gypsies in concentration camps alongside the Jews. The miners’ anti-Gypsy prejudice has received official backing in the form of government statements claiming that the majority of the anti-government protesters are Gypsies: people of poor quality. And then there’s the fact that the miners came to Bucharest in their uniforms – one of their number told me that his uniform ‘made him feel better’ as he travelled to the capital from the Jiu Valley. More significantly, when Ion Iliescu addressed the departing miners he spoke of their ‘patriotic awareness’ and ‘exemplary devotion’. He wanted to establish a National Guard of ‘well-trained, determined and resolute people to intervene in exceptional moments’. And he urged the miners ‘to maintain their spirit of mobilisation’. So, in the heat of the moment, a relatively unreformed Communist had resorted to the language of fascism to celebrate the salvation of his so-called fledgling democracy. What it was that decided the miners to act so violently is difficult for an outsider to establish. And perhaps for an insider, too: many of the Romanians I have spoken to in Bucharest explained their behaviour by saying that the miners are primitive people: they come from the villages and they will simply do what they are told. But one American journalist, who recently spent a week in the Jiu Valley, told me she was treated hospitably and well. The miners had been friendly towards her, and indeed as she slipped in and out of the Intercontinental Hotel, which overlooks University Square where much of the violence took place on 14 June, some of the miners would recognise her, stop beating up a hapless passer-by and come towards her waving and smiling.

The opposition’s response to these events has been particularly depressing. The National Liberal Party, led by Radu Campeanu, is the most significant and sophisticated of the opposition parties in Romania. With the world’s media in attendance, they called a press conference to deliver their verdict. A forthright and trenchant condemnation? A clarion call to the world to try and put pressure on the Government to change its barbaric habits? Not at all. The Liberal Party MPs took the events in their stride. Of course we don’t approve, they said, but we will go to Parliament as we planned and try and act as a constructive opposition. No claims, no accusations – nothing to give the Government cause for concern. It was as if they had expected nothing better of Romania’s democratic experiment.

Enamoured though they are of Iliescu, the miners were no friends of the Ceausescu regime. In 1977, 35,000 of them took on the Romanian Communist Party in a long-running strike in pursuit of better food supplies, more housing and higher pensions. Their efforts were in vain and subsequently two of the strike leaders died in ‘accidents’. The miners now see Iliescu as their liberator. He has increased their salaries to nearly three times that of the average factory worker, five times that of a teacher, and they responded decisively in his hour of need, coming to Bucharest immediately on hearing that the Government was being challenged by opposition protesters rioting in the streets. One miner described how he was watching television in his home near Craiova when the transmission was interrupted. An hour later programming resumed. Iliescu announced that fascists and Iron Guardists were trying to stage a coup and called on the people to save the revolution. ‘So I went out on the street and talked to some of my neighbours,’ the man told me. ‘We decided to go down to the mines. There we put on our uniforms and headed for the station.’ They travelled to Bucharest in buses and trains specially laid on. And what did they plan to do? ‘Well, we knew that Iliescu would be there to welcome us. He always is. And he told us what to do.’

And when they had done it, Iliescu thanked them. His speech to ten thousand of the departing miners was remarkable. There was not a hint of complaint about their lawlessness (though he has since conceded that there may have been ‘excesses’): the speech was all gratitude to the miners mixed in with wild accusations about a pan-European movement of right-wing forces and a revived Iron Guard trying to destabilise the country. The Stalinist tactic of creating a hidden external enemy was employed to the full.

Many intellectuals in Bucharest predicted that Iliescu would behave in this way. It is indeed remarkable that 85 per cent of the people (according to the official figures) voted for a man who was once a close colleague and friend of Nicolae Ceausescu. Iliescu’s overwhelming victory in the elections both requires and defies explanation. It is indisputable that he received fervent support in the campaign. He gave rallies in every major city in the country except Timisoara: the birthplace of the Romanian revolution has the reputation of being the country’s most liberal city and Mr Iliescu obviously thought it unwise to risk an appearance there. But in those places in which he did appear he was mobbed by thousands, even hundreds of thousands, of adoring supporters. At one rally I saw an elderly man make an improbable leap into the air, overcome with excitement at the news that the great man’s arrival was only a few minutes away. A huge roar went up as the leader was driven to the podium in a well-chosen, battered car. Women waving flowers were in tears as he spoke of liberty, democracy and the glory of what he likes to call a workers’ revolution.

Many in the crowd had been bussed-in for the occasion just as they used to be for the demonstrations in support of Ceausescu. Indeed, the rallies bore an uncanny resemblance to those held for the former dictator. I started talking to a woman at a Front rally in Bucharest who said that she loved Iliescu and Petre Roman, the interim Prime Minister, too. But our conversation was cut short. Another woman, whom I had never seen before, came up and told my interlocutor to stop talking. ‘He’s a liar,’ she said, pointing at me. ‘Liar, liar.’ It was a dispiriting reminder that many former Communists now think of foreigners in much the same way as they did six months ago. The hostility I felt at that rally was repeated during the first meeting of the new parliament a few weeks later. During one of the breaks in the proceedings I approached a group of new National Salvation Front Members of Parliament and asked them for their impressions of their new workplace. ‘Who are you?’ they replied, and before uttering a few noncommittal and monosyllabic comments insisted on a minute examination of my Romanian identity papers.

Why did a man who was once a close friend of Ceausescu win? As far as I was concerned, the chief issue in the election was obvious: what was the best way of using a vote to minimise the possibility of another dictatorship? But for the majority of Romanians the issues were different. Four million ex-Communist Party members had their own past to worry about. Mr Iliescu was always the candidate least likely to organise a thoroughgoing purge that would disrupt their lives. Furthermore, his post-revolutionary interim government had delivered: it had delivered food, heat and light – pitifully little of these things, it’s true, but more than Romanians have become used to. The bulk of the electorate, moreover, clearly associated Iliescu with the overthrow of Ceausescu. Unfortunately, there would have been more reason to do this if the persistent rumours about Iliescu having staged a coup were true. In fact, there is still no convincing evidence that there was a coup. There is more reason to believe that Iliescu successfully rode the back of a genuine popular uprising.

In doing so, he had the active support of the petty power brokers throughout the country. Directors of co-operatives, small town mayors and other local bosses all identified with the Front. They understood that it offered the best chance of stability and of their continuing prominence. It was these people and not the Front’s leaders in Bucharest who orchestrated the intimidation in the campaign: intimidation which made the opposition parties fearful of campaigning in a village if they didn’t know someone there who could afford them protection.

Basking in the legitimacy conferred by running the interim government, Mr Iliescu was never too troubled by the opposition parties. Ceausescu had managed to suppress every trace of a dissident movement. The Presidential candidates either had to come from the ranks of disaffected Communist Party members or from the exile community. The opposition chose two exiles: Ion Ratiu, a millionaire property dealer and shipping magnate from London, and 74-year-old Radu Campeanu from France. Neither overcame the handicap of not having suffered with the people whose votes they sought.

It was not only the charge that they had been leading a life of luxury throughout the Ceausescu years that undermined the opposition candidates, however. They also faced the problem of putting their case to the people by means of a television station which, particularly in the early stages of the campaign, clearly favoured the Front. But this significant fact was completely lost sight of as soon as the much heralded International Election Observers gave their nearly unanimous verdict: ‘The elections were rigged but no more than one would expect,’ they said. ‘The elections,’ they declared, ‘should be considered valid.’

This was the first time I had seen election monitors at work and I will certainly never take such people’s views seriously again. Most of them arrived in Romania two days before the ballot. They spent a good deal of the time eating meals, often with government and election officials. The National Salvation Front leaders told them that everything had been basically fair in the campaign, except for a few attacks on their own party. This was a blatant obfuscation of reality. The election officials, of course, said that they were doing a very good job in difficult circumstances. The monitors met the opposition too, and listened to allegations that many of their offices in the countryside had been vandalised and their Party activists beaten up. But they simply didn’t have the time to investigate these claims properly, commenting only that the documentation they were presented with (hastily assembled photographs of smashed offices and injured people with a few signed affidavits) was not as thorough as they would have liked. Then, having said that they intended to see the whole process right through to the end, most left before the counting had even begun. In fact, the overriding concern of the observer groups was to secure the greatest possible publicity for themselves by being the first to hold a press conference in which they declared their verdict: an altogether more rewarding task for active politicians than sitting around in the counting centres. Despite the fact that they didn’t know what had actually happened, the monitors felt completely unabashed in declaring themselves to be basically satisfied with the electoral process.

It is probably the case that the rigging on the day wasn’t enough to affect the result, at least in the Presidential race. But it’s simply impossible to gauge the consequences of six months of biased TV coverage. What matters now is not whether Romania has enjoyed democracy since the revolution, but whether it will do so when the National Salvation Front starts to govern in earnest. Before the miners did their work, there were reasons to believe that the Front could deliver genuine pluralism. There is freedom of speech; and the new Parliament does contain an opposition, even if it is small and now distinctly battered. The Parliament’s chief task is the drafting of a new constitution, which all parties agree should be designed to underpin democracy and civil rights. Moreover, the Front is so heterogeneous that there is a real chance of splits emerging within the Party. It is to be hoped that they will, for a split might subject the Government to effective Parliamentary scrutiny. In addition, the new Prime Minister, Petre Roman, who, as a member of the Romanian élite, lived in France for three years, has surrounded himself with a group of radical and technocratic ministers, and they are acutely aware that Romania needs foreign investment (and therefore foreign approval) if it is to reach anything like the standard of living enjoyed by its neighbours.

The case against the view that a significant degree of democracy will be achieved is rather more convincing. The events of mid-June demonstrate that the President is prepared to stop at nothing to save his regime. Even if Petre Roman’s reformists remain in place, they are battling against one of Europe’s biggest and best bureaucracies and it is already tightening its grip. Take the new agricultural reform programme. The issue is clear enough: should the land, which the peasants say was stolen from them, be returned? ‘Yes,’ says the Front, and in any village you can find people who will tell you that they have reclaimed what was theirs. But one should always read the small print. The peasants can own the land, says the legislation, but cannot sell it. In effect, though they don’t seem to realise it yet, the peasants have nothing more than a licence to work on land which they consider to be their own.

Do most Romanians even want Western-style democracy? Many clearly do, but one must never forget that thousands of people cheered and waved at the miners as they swaggered around the capital in trucks, waving their clubs and their axes in the air. The ambiguous attitude to liberalism of many Romanians was demonstrated during the trial of Nicu Ceausescu, Nicolae’s scandalous son, which began recently in Sibiu, the city in which Nicu had his power base under the old regime. Prosecution evidence showed that many of the rumours surrounding Nicu were true. He did have food specially flown in from Bucharest every night; his dog did eat better than most of Sibiu’s citizens; he did prowl around the couple of bars that the authorities allowed to exist in Sibiu, picking up hapless women.

More seriously, evidence emerged of conversations Nicu held with his mother as the December revolution began to engulf the Ceausescu regime. ‘Give the army weapons so that they can kill,’ she kept yelling. Nicu did not demur. He claims that he is not guilty of the charges laid against him: genocide and the illegal possession of weapons. ‘Of course I had weapons without authorisation,’ he said. ‘How could you expect anyone in my position to bother with that?’ He even volunteered an apparently self-damning description of the dying moments of the old regime when it was clear that the revolution would succeed. ‘Someone asked me,’ said a broadly-grinning Nicu in his evidence, ‘what we should do. I told him that it was everyone for himself: Pack your bags and run – the game’s up.’ The audience in the courtroom laughed. No one seemed to be taken aback by this admission of the weakness of his power base. The next day (by which time the trial had been shown on television) I asked people what they had thought of it. I was repeatedly told how honest and amusing Nicu was. He was a popular figure; even some of the anti-Communist protesters camped out night and day in Bucharest’s University Square actually liked him. ‘He could not be expected to behave otherwise,’ they told me. ‘And after all, he had not sought power: it had been handed to him on a plate and who could blame him for having a good time. I would have probably done the same.’

And so the revolution has been betrayed even by the people who made it. I don’t say that with Western standards of democracy in mind. ‘Down with Ceausescu!’ the people roared last December. And yet five months after so many young lives had been sacrificed in the cause of bringing Ceausescu down, the dictator’s son, an active and senior member of his father’s despotic regime, is praised for his charm and wit. And that is only one of the many absurdities in Romanian life. Four months in the country have been enough to persuade me that Eugene Ionesco and Tristan Tzara, both Romanians by birth, were not such fantasists after all. At a recent anti-government demonstration low-flying helicopters swooped over the protesters. Leaflets emerged from the belly of the craft. Everyone assumed it would be a warning to clear the area. But as they fluttered to the ground, the bewildered crowd found that they were being invited to an air show. ‘Come to an air show,’ the leaflets said. ‘Those with a weak heart are advised not to attend!’ The absurdities follow one after the other. Nicolae Ceausescu did have a brother called Nicolae Ceausescu. Their father, the story goes, was drunk at the second christening. If you want to drink beer in a restaurant, as any Romanian will tell you, you ask for tea and await the teapot in which it is served. But perhaps the greatest absurdity of all is that the people of Romania have elected to the Presidency a man who has shown himself to be antithetical to many of the revolution’s aims and who, as we now know for sure, is prepared to use as much repression as is necessary to maintain his hold on power.

Send Letters To:

The Editor

London Review of Books,

28 Little Russell Street

London, WC1A 2HN

letters@lrb.co.uk

Please include name, address, and a telephone number.