To those who first encountered British sociology in the early Seventies, as I did, the discipline seemed infinitely more exciting than its counterpart across the Atlantic. Perhaps exhausted by the unravelling of the Parsonian system, American sociology had retreated from the pursuit of social theory toward the perfection of quantitative technique and the practice of microsociology. Each had its uses, but neither seemed to take up the challenge that the classical sociologists, like Marx, Weber and Durkheim, had posed for the field: namely, to describe the relations that held societies together and to explain the processes whereby these might continue or change.

British sociology, by contrast, was displaying the advantages of backwardness. Perhaps because it was less established and still deeply influenced by analytic philosophy and anthropology, it remained a highly theoretical pursuit, focused on large questions about the nature of society and social change. Perhaps because it was British, issues of power and stratification were central to the enquiry. Methodological debate seemed endemic. Here was a discipline, long-established in America, that still seemed to lack a clear-cut identity in Britain, yet, out of antediluvian debate, was making advances that would influence the course of social science around the world.

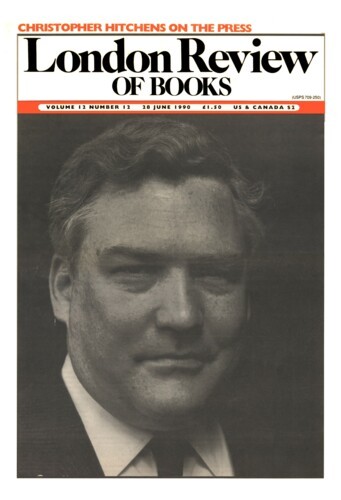

In this milieu, W. G. Runciman was a seminal figure, who appeared as puzzling to the uninitiated as the discipline he studied. He was an internationally-known sociologist at a university that apparently had no department of sociology. It was rumoured that Runciman rarely taught. Indeed, he appeared to work for a shipping company, doing sociology in his spare time. His book on Relative Deprivation and Social Justice was a path-breaking effort to apply historical research and survey-data to normative issues, widely cited to show that British sociology was not entirely theoretical. Yet those who searched the card catalogues for Runciman’s other empirical work found instead a serious study of Plato’s later epistemology and Philosophy, Politics and Society, a co-edited series of books that epitomised the hegemony of philosophy over social science in Britain. What was one to make of all this?

Twenty years later, a good deal of the answer can be found in Confessions of a Reluctant Theorist. This is another in the series of selected essays that the entrepreneurial editors at Harvester have been commissioning from distinguished academics. On the whole, they gather together the minor works of those who have written some great ones. The results, as might be expected, are uneven. This particular collection includes everything from a fine synoptic essay on Runciman’s approach to social theory, originally delivered in 1986, to a rather slight political tract entitled ‘Where is the Right of the Left?’, itself so full of confusing semantic distinctions as to constitute prima facie evidence for the impossibility of finding a stable political centre in Britain.

In between are essays on such diverse topics as the origins and end-points of the Greek polis, stratification in Classical Rome, social mobility in Anglo-Saxon England, the consequences of the French Revolution, British industrial relations, and the contradictions of state socialism in Poland. Many seem to constitute preliminary sketches for the second volume of Runciman’s masterwork, A Treatise on Social Theory. Of these, only the slightly dyspeptic review of a book on Roman history is so lacking in wider import that it might better have been dropped. The other essays do not constitute the most systematic expression of Runciman’s approach to sociology – for that the Treatise is indispensable – but they provide a glimpse into the intellectual trajectory of an extraordinarily learned, yet curiously down-to-earth sociological mind.

The book opens with a splendid intellectual autobiography reminiscent of those essays one must write for admission to graduate school.

This one can be commended to any aspiring postgraduate wondering what it means to pursue learning in an environment marked by multiple counterpressures, both worldly and intellectual. We learn that Runciman’s interest in sociology was first inspired, not, as might be expected, by that great systematiser, Talcott Parsons, but by George Homans, a more modest theorist whose own work was firmly rooted in historical enquiry and the insistence on ‘bringing men back in’ to sociology.

With unerring instincts and a fellowship to the United States, Runciman sought out the best empirical sociologists of his day, while simultaneously writing a dissertation on Platonism to secure a research fellowship at Cambridge. Here is encouragement for any graduate student forced into a diversionary path towards his ultimate goal. Here also is the empirical pedigree one would expect of Relative Deprivation and Social Justice. He began his career solidly trained in quantitative methods and sceptical of the value of grand theory – hence, the strange title of these ‘confessions’.

Back in Cambridge, however, Runciman found himself inexorably drawn into the methodological debates of a discipline undergoing a profound identity crisis best encapsulated in that quintessentially British question: ‘What is there in sociology which is neither second-rate history nor second-rate philosophy?’ The effort to provide an answer drew many of the finest British sociologists of Runciman’s generation and beyond into a theoretical quest, such as those in America had generally forsaken. The results have been prodigious. The works of Perry Anderson, Ernest Gellner, Anthony Giddens, Geoffrey Hawthorn, Steven Lukes, Michael Mann and Runciman himself, not to mention many others, take up the challenge of the classical sociologists, often on the terrain of world history.

Runciman’s own response to the question of what sociology must do is similar in scope to those of the others but distinctive in content. As the opening essays in these Confessions indicate, it owes as much to Darwin, Spencer and sociobiology as to Marx and Weber. Runciman argues that sociology must do for the study of societies what Darwin did for the study of the species: specify the processes whereby societies move from one distinguishable type to another, identify the units selected by that process with the functions they perform, and indicate the direction it has taken.

This is no small task, but over two decades Runciman has devised a theory designed to accomplish it. He argues that the roles and institutions characteristic of a particular type of society are eventually superseded by others through a process whose engine is the competition among multiple social groups to augment the power of the roles and institutions they occupy. As these practices, and the institutions associated with them, change, the power of the groups who employ them rises or declines in such a way as to alter the overall distribution of power in society. Power itself is said to come in three modalities: economic, ideological and coercive, more or less after the Weberian triptych. There is no ultimate telos to this process and considerable randomness within it, but the consequence is a delimited range of societies defined in large measure by their systems of social stratification.

The opening essays in these Confessions provide a highly compressed account of this theory, especially in relation to its intellectual precursors, and the subsequent essays tend to reflect rather than elaborate it systematically. Nonetheless, the strengths of the approach are clear. By insisting that institutions and the practices associated with them are central to social change, Runciman takes a timely step beyond the arguments of his classical predecessors, who gave more prominence to social groups. By assigning a historical role both to the conscious pursuit of power and to the unintended consequences that follow from the adoption of particular practices, the theory slips nicely between the shoals of excessive determinism and the inordinate voluntarism currently fashionable in some circles. By placing relations of power at the centre of his analysis, Runciman captures one of the most consequential features of social interaction. Here is a theory with which to conjure and a set of case-studies dazzling in their variety and detail. Few, surely, can rival the scrupulous reasoning and wide scholarship that Runciman brings to his subject.

However, Runciman has good reason to be a reluctant theorist. He is as good at it as they come. But the task entails wedding broad generalisation to the facts of multiple empirical cases, and this is a difficult marriage to consummate. The more general the ambit of a theory, the more difficult it is to provide substantive explanations for particular cases, and Runciman aims at the most general of theories. Perhaps for that reason, there is something slightly formal about the results.

Consider the impressive essay in this volume about the origins of states in archaic Greece. He argues persuasively that the development of a state depends on the accumulation of all three kinds of power in the same hands or roles. Using this framework, he is able to demolish a number of monocausal theories about the origins of states. However, to the natural and important question about why power should accumulate in some places rather than others, Runciman has a very diffuse answer. He argues that power logically tends to accumulate, but only in the absence of internal fragmentation or external conquest, whose occurrence is not explained, and in response to triggering events of multiple and unspecified sorts. In the Greek case, it turns out that a host of ancillary conditions allowed the accumulation of power and the development of states, including population growth, geography, the appearance of arable farming, pre-existing religious practices, improvements in military technique and the influence of trade.

We learn a great deal from this analysis, but not necessarily what we most want to know: were some conditions more central than others to the development of states? In theoretical terms, what we have been given is primarily a specification of the broad process whereby the roles constitutive of a state are constructed, itself useful but distinctly limited in explanatory bite and rather closely related to the definition of a state in the first place.

Now this is partly a matter of taste, and one of the great strengths of Runciman’s approach to the explanation of social change is that it allows for the operation of a wide range of historical forces, complex multicausality, and the impact of random events. He deliberately resists assigning general causal primacy to contextual factors that might operate in only some instances, yet manages to identify a very specific set of processes common across the historical spectrum of social change. This is a substantial achievement, and those who absorb his social theory will almost certainly return to it to organise their own thoughts on the subject. Like few others, it seems to do justice to the remarkable variations of history. However, precisely because the theory is so general, it forces us to look elsewhere for the explanation of particular cases.

Among the factors that Runciman acknowledges might matter to particular cases are demographic change, pressure from the international system, improvements in military technique, innovations in economic organisation, and the like. Few would disagree with such a list, but many might feel that the primary task of a theory of social change is to explain which of these have most systematic importance across history for certain generic kinds of outcome – a question from which Runciman shies away. Others might seek a greater sense of specificity even within his own theoretical framework. The component parts are all there – institutions, roles and practices, competition among social groups, three forms of power, unintended consequences – but it is not always clear precisely how they relate to one another, especially in terms of causal primacy. Above all else, one wants to know: what force does the selecting in this ultimate theory of social selection? Why do some institutions emerge triumphant in the end over others? His answer is highly eclectic, and perhaps for that reason realistic, but it leaves some aspects of his theory oddly elusive.

Runciman’s treatment of culture is also unusual for a sociologist. Although the practices associated with particular cultures lie at the centre of his social dynamic, Runciman treats them primarily as random inputs into the overall process of social selection or as instruments in the hands of those pursuing power. His theory tends to devalue the causal significance of what the historical actors thought they were trying to do, at least to the degree that they thought they were doing something other than seeking power. It relegates to the sidelines the panoply of cultural meanings and considerations that a Daniel Bell or Clifford Geertz might employ to explain the direction of society.

We see this reflected in Runciman’s masterful essay on the French Revolution. Taking up a number of themes in the recent historiography, he argues that the Revolution was literally ‘unnecessary’: first, in the sense that it took place only as a result of unforseeable coincidences, and second, in the sense that the observable differences between the social structures of 18th and 19th-century France would have occurred anyway. Here we have one of the most systematic analysts of social change arguing that the event often said to be definitive of the modern world was largely a random occurrence and one without significant consequences for social structure. The insistence on the operation of chance in history and an overriding interest in stratification are two of the leitmotifs of Runciman’s work.

This is not the place to take up the precise merits of Runciman’s analysis of the Revolution, although it has many. More interesting are his conclusions that a clash of world views had relatively little to do with the outbreak of the Revolution, and that the cultural changes associated with it had no major impact on subsequent class relations. He does not ignore the contribution of culture to class relations or the global impact of the Revolution. But, here as elsewhere, the interpretative content of specific social practices does not play a prominent role in his account of how societies evolve. This stance may derive from the radical distinction drawn in the first volume of his Treatise between social explanation and the more interpretative sort of enquiry he terms description. However, at times one feels that his account of social stratification and change might be less clinical and more conclusive if it gave greater weight to the factors that precisely such description is designed to capture.

W.G. Runciman emerges in these essays as a less puzzling but even more inspiring figure than he seemed in the early Seventies. He has devised a sweeping social theory that places him among the most distinguished British sociologists of a theoretically-inclined generation. The remarkable range of cases dissected with erudition and rigour in this collection render it difficult to review but very useful for demonstrating how Runciman’s social theory can be applied to concrete problems. In this book, the reader will find precisely what the title advertises: a glimpse into the reasoning by which a versatile sociological mind fashions fruitful theory out of the careful consideration of diverse historical cases.

Send Letters To:

The Editor

London Review of Books,

28 Little Russell Street

London, WC1A 2HN

letters@lrb.co.uk

Please include name, address, and a telephone number.