The writer, grizzled, sun-tanned, wearing only desert boots, shorts and sunglasses, sits outdoors in a wicker chair, checking a page in his typewriter. The picture appears on the covers both of Ian Hamilton’s Writers in Hollywood and of Tom Dardis’s Some Time in the Sun and instantly announces several elements of a familiar legend. Even in black and white the image is full of warm shadows, and the uncropped version fills out the legend a little further. The desert boots are missing from the Hamilton cover and so is the landscape above the writer’s head: a hillside gracefully cluttered with dark pines and white villas, a reminder that California and the Mediterranean inhabit some of the same reaches of fantasy and even geography.

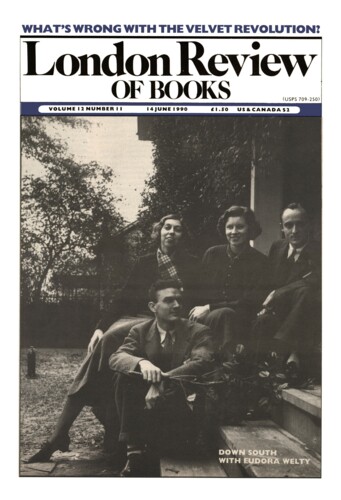

The writer is only half-working, or playing at working; his real place of work must be elsewhere. He is not at home, because they don’t have weather like this at home, at least not all the time. Couldn’t California be the writer’s home? Of course, it is the home of many writers. But not in this legend. Hollywood is not serious, it can never escape its mixed condition of moneybarrel and dream, land of locusts and last tycoons. ‘One day one leaf falls in a damn canyon up there,’ Faulkner growled, ‘and they tell you it’s winter.’ The figure we are looking at, as it happens, is Faulkner, photographed at the Highland Hotel, Hollywood, in 1944. It would help if he was writing The Big Sleep, as he was late in that year: the sunny patio begets Philip Marlow’s dusty office and his mean, incomprehensible streets, another California.

The legend has faded now – fortunately, since it did so much damage, and not only to famous sad cases – but it is important to understand its terrible appeal. Just think: Hollywood allowed writers to fail and then despise the system they failed in; to succeed and despise themselves; to despise others for lacking the know-how they possessed; to dip into glamour without believing in it; (more rarely) to live very well by doing a job decently; (not least) to avoid, sometimes permanently, what they regarded as their real work.

Ian Hamilton’s intelligent, well-informed and often funny book is a history of this legend and what lurks around it. Hamilton’s wit is discreet, a matter of careful phrasing rather than the large gesture. ‘Big-name wrecks’, for example, ‘celebrity drunks’, or the delicately restrained suggestion that Selznick was ‘less earnest but more fanatical than Goldwyn’. Hamilton’s commentary on Hollywood drinking lore is shrewd, undeceived, uncondemning. For instance: Faulkner and the writer/producer Nunnally Johnson meet for the first time, Faulkner cuts his hand opening a pint of whisky, allows the blood to drip into his hat, swigs half the whisky, hands the bottle to Johnson, who drinks the other half, and the two men go off on a binge, to be discovered three weeks later in an Okie camp. Hamilton asks: ‘Do we believe any of this? Almost certainly not. Most Hollywood “legends” were the work of screenwriters trained in the manufacture of big scenes: the two taciturn Southern gentlemen bonded by the bottle, the blood dripping into the hat, the half-pint knocked back in a few swallows, the three weeks (three weeks) in an Okie camp ... ’ Still, probably Faulkner and Johnson did get on well enough. ‘More than likely,’ Hamilton says, they ‘did bury a few drinks. They may even have stayed up all night.’

However, Writers in Hollywood does take most of its information secondhand, and the narrative is a bit desultory, as if Hamilton didn’t always know why he was retelling this anecdote rather than that. He informs us, for example, how his book might have been seen fifteen years ago (‘as a riposte to those theories of screen authorship that pay exclusive homage to the “vision” or “personal signature” of the director’); how ‘the sometimes pure in heart’ may read it now (‘as an admonitory parable’ about a writer’s life not being easy, even in the sun); but says very little about any other readership. The implication, I think, is that this is a book more for people interested in writers than for people interested in Hollywood. I suppose we (and Hamilton) are the sometimes pure in heart, but the joke is a little forlorn, and the book, in spite of its alert irony, seems rather depressed and depressing, its last image the body of the drowned writer in a pool in Sunset Boulevard. Still, the story is depressing, perhaps more so than Hamilton thought when he began the book.

Faulkner probably worked harder in Hollywood than he liked to pretend he did, and what Hamilton calls ‘tales of truancy’ in respect of writers in movieland generally function through a disastrous marriage of complementary myths. The writer is a romantic delinquent, either drunk or lovelorn, who filters his Hollywood money through an idea of distance from the place, literal or metaphorical. This ensures that however hard he works, his real work is kept from the movies. The studios are generous and open in their recognition of big names, but the names are all they want, and they can scarcely be expected to depend on these unreliable types for real labour. This means that hackwork becomes the norm, the often honourable but always limited measure of what is possible in American movies. Hollywood is not a history of missed chances, in the sense that we lack the great (literary) movies we might have had. But it does offer an image of cultural breakdown, of mutual snobberies (about money and entertainment, about art and intelligence) getting in each other’s way. The great movies we do have are made in spite of, not because of, such stiffnesses and incomprehensions.

‘People don’t go to the movies to read,’ D. W. Griffith said: but they did, not least to read Griffith. ‘For her who had learned the stern lesson of honour,’ a title card in Birth of a Nation tells us, ‘we should not grieve that she found sweeter the opal gates of death’ (Griffith’s italics – the card had Griffith’s monogram in the corner). It is intriguing to think of silent films thriving on such fulsome stuff, and even on verbal wit; of Anita Loos’s dialogue on cards converting Douglas Fairbanks from ‘a buffoonish athlete’ into a ‘credible screen smoothie’. Even in the silent era Hollywood was trying, often with comic effects, to sign up ‘Eminent Authors’; but usually settled for New York or Chicago wits, ex-dramatists or newsmen. Sound stepped up the process, and the grounds of the legend were laid: hacks trapped in a series of writers’ buildings, jumping to the barked commands of the studio bosses, famous names twiddling their thumbs for huge salaries. Writers then began to get organised, quarrelled with their studios:‘Writers of the world unite!’ Herman Mankiewicz sardonically proclaimed. ‘You have nothing to lose but your brains!’

Hamilton evokes the stints in Hollywood of various distinguished figures – Fitzgerald, Aldous Huxley, Nathanael West, the photogenic Faulkner – but also looks at the careers of resident screenwriters, like Dudley Nichols and Nunnally Johnson. He charts the war efforts of Hollywood writers, studies the battles for credits surrounding Citizen Kane, Casablanca and Hangmen also die, and the work of the writing teams of Wilder/Brackett and Goodrich/Hackett or is it Hackett and Brackett? There is also a Leigh Brackett, no relation, who worked on The Big Sleep, several Howard Hawks films (Rio Bravo, Rio Lobo, Hatari) and The Empire strikes back. Hamilton has much fun with film historians’ confusion in this zone. Just who was it who put the alcoholic Dashiell Hammett on a plane in 1937, or perhaps 1938? Hamilton warms to the work of Preston Sturges (‘there is always a touch of film criticism in his films’); but his story sinks again with the Hollywood witch-hunts of the late Forties and early Fifties. Almost no one comes out of this episode well, and the only slightly cheering thing is that many of the more abject participants did later see (and say) how disgraceful the whole show was.

Writers in Hollywood suggests not wasted talent but a horrible eagerness for compromise, on the part of both writers and studios, combined with a willingness to think poorly of themselves and of each other. The miraculous thing is that so little of this appears in the movies of the period, which for all their evasions and reticences give the impression of powerful fantasies being let loose and explored. Hamilton fondly evokes the filmscapes of the immediate post-war years, for example (‘the early-hours backstreet, the lone street-lamp, the drizzle, the flashing neon sign’), and wonders whether the themes of these movies (‘disloyalty, revenge, neurotic instability, mental cruelty, obsession’) were ‘chosen by the market, or did they signify some aberration in the merchant?’ Well, probably some weird combination of the two, with the proviso that movies are ordinarily like this.

The blurb suggests that this is ‘a comprehensive history of the relationship between Hollywood and the written word’. One shouldn’t believe a blurb, but this proposition sounds attractive and is doubly misleading. First, because Hamilton has written another sort of book: about the relationship between Hollywood writers and Hollywood studios; between Broadway and Hollywood; between writers and screenwriters; between screenwriters and national and international politics. The proposed comprehensive history could be done, and might be worth doing: but it would require close scrutiny of masses of scripts and revisions of scripts, and of the shifts between scripts and finished films. Hamilton does some of this, to very good effect, in relation to I am a fugitive from a chain gang. But he doesn’t concentrate on it, and probably rightly, because ‘the written word’ suggests mainly synopsis and dialogue, whatever may look like a text at any stage of moviemaking, and writing in movies involves a good deal more than this, even if the writer is changed every day and the director takes all the credit. Shape, structure, implication, ideology are all written too, do not simply materialise out of the unmarked image; and the ‘written’ in this context may often be spoken, improvised, a meeting of writer, actor/actress, director.

When Alexandre Astruc, in 1948, spoke of the caméra-stylo, the camera that writes, he was partly trying to claim some of literature’s prestige for film, but mainly urging us to think about film language: ‘The fundamental problem of the cinema is how to express thought.’ The stylo, incidentally, as we learn from one of Hamilton’s sources, may have been invented by Nathanael West, who is said to have regarded the movies ‘as an immense fountain pen’. It is true that West also regarded them as ‘an adding-machine’. Astruc was equally opposed to verbal and to visual clichés; there had to be a better way of indicating the passage of time than by showing falling leaves, and (although Astruc doesn’t say this) there must be many ways in which the cinema, like any other language, not only expresses thought but invents and permits thought which has not previously come into being. This means, Astruc argued, that ‘the scriptwriter directs his own scripts: or rather, that the scriptwriter ceases to exist, for in this kind of film-making the distinction between author and director loses all meaning.’ In practice, at least in most American films, it is the search for a sole author which loses all meaning, and the idea of collaboration seems merely lame unless we are going to look into it. The question of writing remains: not who writes, but what writing is in this medium, the nature of the product upon which acts of interpretation descend.

This may sound like Roland Barthes, but the question is admirably formulated in a New Jersey court ruling of 1905, quoted by Hamilton: ‘a photograph which is not only a light-written picture of some object, but also an expression of an idea, a thought, a conception of the one who takes it, is a “writing” within the constitutional sense, and a proper subject of copyright.’ As Hamilton says, ‘several questions are begged here,’ but some good questions are implicitly asked too. Could a light-written picture not express an idea, a thought, a conception? If we don’t want to call this expression ‘writing’, what shall we call it? And if in the court’s definition the ‘writer’ seems to be the photographer (‘the one who takes it’), what are we to make of the other candidates for the job, the one who scripts the photographer’s object, the one who devises his angle, the one who puts the photographs together? This is a question not about authorship – unless we need to settle a copyright suit – but about the history of what gets onto the screen. We might still say such history doesn’t matter, that we care about other things in movies, but then the onus would be on us to say what it is we care about.

There is a subtle development in Hamilton’s book on just this topic. Early on, he tells us that ‘once an argument about attribution begins, there is almost no point in pursuing it’. Only ‘almost’ no point, we note, and a little later Hamilton says that ‘we can learn a lot about the difficulties that face the film historian by attempting to identify the “author” ’, of a particular scene. The interest is still with the historian, but later Hamilton suggests that the dispute about the authorship of Casablanca ‘bears somewhat on the character and quality of a movie that most of us know, or think we know, by heart. ‘Somewhat’ is the voice of Hamilton’s modesty. It is the ground of the dispute not the settlement of authorship that interests us, and it is a virtue of Hamilton’s book that it invites us to think not only of film history but of what we are to do with it.

Send Letters To:

The Editor

London Review of Books,

28 Little Russell Street

London, WC1A 2HN

letters@lrb.co.uk

Please include name, address, and a telephone number.