I have always wondered when my grandparents realised they would never see Russia again. In July 1917, when they locked up the house on Fourstatskaya Street in Petrograd, left the key with my grandfather’s valet and set off with a party of servants for Kislovodsk, a spa town in the north Caucasus, they told the children that they were all going for a summer holiday. That is what they said. But what were they thinking? The disintegration of the Provisional Government was underway. One of their sons swears he overheard his father whispering to another relative: ‘I’ve got to get them out of here.’ And my grandmother, whatever reassuring fictions she may have told her children, took her jewellery with her, and ordered the maid servants to pack a trunk of family valuables. Some shadow passed across her mind, and she took precautions, and that is why there is a silver ewer and basin in my house, one piece of family linen with a monogrammed crest and two bits of jewellery. Without that instant of hesitation, they might have been lost.

Yet I suspect that even when Russia’s Black Sea coast was receding astern in the spring of 1919, my grandmother and grandfather still kept the hope of return alive in some unreconciled region of their minds. My grandfather was heard to remark that it might be possible to join Kolchak’s White Army in Siberia. In the meantime, the boys would be enrolled at St Paul’s School in Hammersmith. When I look at the photographs of my grandparents on their farm in Sussex, it is not until the mid-Twenties, after the definitive defeat of Kolchak and all the rest, after the recognition of the Bolshevik regime by the Western powers, that I begin to see – imprinted in their faces – the recognition that they would never return. A new grimness and bleakness are evident in their eyes. They have come face to face with the irrevocable.

This is one of the great themes of exile: how the temporary becomes permanent, how the doubt kept at bay grows into a certainty, how, finally, the candle gutters out. What was remarkable about the White Russians is how long they cupped that candle with their hands. Packed suitcases were stored under beds in miserable Paris apartments for decades until death put an end to pretending. Children born in exile were raised to believe that one day they would return to the lost kingdom. Some of these children regarded the Nazi invasion of June 1941 as a providential sign that the time for return had come at last, and they died in the Russian snows, clad in Wehrmacht uniforms. Their deaths exemplify the incorrigible hold of fantasy upon exile life.

Then there is the theme of remembrance as torture. Hunting for mushrooms under the dark trees at the bottom of the ‘English garden’; the three bells at Russian stations; the crunch of felt boots on white snow: in every miserable hotel in Clichy, in every little cottage in Clamart in the Twenties, such memories had the power to transport the haunted rememberer across time only to hurl him back into the odour-filled prison of Russian poverty with its black bread, cabbage soup and paraffin stoves.

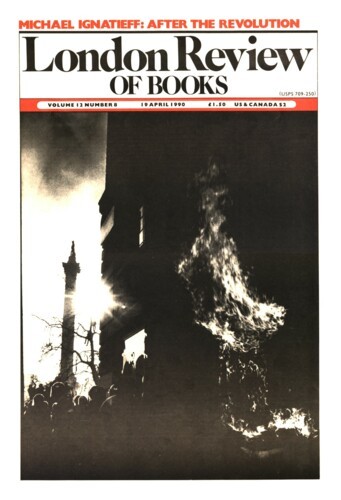

To the themes of memory as torture and the slow asphyxiation of hope must be added the theme of defilement: the estate pillaged and set to the torch, the Chinese silk ripped from the walls, the icons looted or tossed onto pyres, steeples toppled and family bookshelves rifled. It is the cruelty of parallel time that makes the defilement so hard to bear: knowing that as you emptied another dustbin in Nice or took another fare in your Paris taxi, some stranger, some nest of families, was partitioning your apartment on the Liteiny Prospekt or on Galernaya Street and was either tearing up your floorboards for fuel, or ripping your curtains for bedding. In my grandmother’s memoirs the passages where anger and grief mix together into something close to despair are elicited by images of desecration: the moment, for example, when she describes how her mother’s estate, Doughino, was burned to the ground, and her brother was made to sweep out the filth in the prison yard of the local town.

There wasn’t only loss and despair, however: exile also offered the possibility of liberation from the chains of the past. As the exiled artist Vitaly Komar remarks in The Other Russia, ‘Russia is an island. And the impossibility of reaching that island can be a stimulus to painting.’ In Speak, Memory Nabokov wrote of the ‘syncopal kick’ of exile, of dispossession so juddering the frame of memory that it roused the artistic imagination to seize that frame and get the once-clearly-seen picture to stabilise into clarity again. If all writing springs from estrangement, from some inextinguishable puzzlement about what is, then one can think of exile as a condition which forces that puzzlement on those who might otherwise have taken their reality for granted.

Inch by inch, instant by instant, Nabokov had to reconquer with his prose a reality which, until exile absurdly supervened, had been his for the asking. To wonder whether exile made him a better writer than he might otherwise have been, to suggest that exile might even have been the precondition of his writing, is just as foolish as wishing that one’s writing could be tempered and deepened by a sharp, but preferably short, dose of Eastern European censorship, imprisonment or oppression. One would not wish exile on anyone, but dispossession did make pre-revolutionary experience unreachable and thus incited a few heroic talents – Nabokov, Bunin, Berberova, Tsvetaeva, Khodasevitch – to reclaim it for the imagination. Thanks to their efforts, the Russian Ancien Régime is a kind of Atlantis of the European mind, as vivid beneath the waves as it was above them.

Norman Stone and Michael Glenny’s book is a scrapbook of Atlantis, an oral history of survivors from the sinking. Many of them were in their eighties when Glenny’s tape-recorder finally reached them in their close, cluttered rooms and for this alone – preserving these ancient voices before they went silent – we can be grateful. What is incredible about these old remembrancers is how much historical time is encoded in their memories. Sometimes it even amazes the exiles themselves, as when Irina Ilovskaya says of her grandmother: ‘Just imagine, she was born in the Caucasus and died in Paraguay.’

Yet how effortlessly memory manages to vault the chasm of revolution, how seamlessly it weaves together a life that might include both the Caucasus and Paraguay. Consider Galina Nikolayevna von Meck, born in 1891 into one of those great families of Baltic German origin which were so much the reverse of the familiar caricature of the Russian aristocracy as muddled, dreamy and incompetent. Her father ran the Moscow-Kazan Railway Company. Her mother was a relative of Tchaikovsky. Galina von Meck was 20 years old when, one evening at the Kiev Opera House, in between acts of Korsakov’s Tsar Saltan, she looked down from her box and saw a man in a black suit push his way through the stalls, point a pistol and fire the shot that punctured Prime Minister Pyotr Stolypin’s white waistcoat with a precise round hole. ‘There was a hush,’ she remembers, and while everyone chased after the assassin who was leaping over the seats to make his escape, Stolypin remained standing, ‘blood slowly seeping through his uniform’.

At a distance of seventy years, Galina von Meck relived the whole scene with a serene conviction that nothing had been lost in all the intervening time. No, she insisted, it was not true that Stolypin made the sign of the Cross when the Tsar appeared at the edge of his box. ‘I was watching him intently, and what Stolypin did, although badly wounded in the stomach, was to raise his left arm and twice wave to the Tsar to go back into the box and keep out of sight.’ A sensible gesture, she points out, and how much more typical of the modernising politician than some gesture of dying reverence for the autocrat, whose secret police, historians have decided, colluded in the assassination. ‘As a rule “if’s” in history are a waste of time,’ the redoubtable Galina von Meck concludes briskly, while adding that if Stolypin had lived, Russian history would have taken a very different course.

‘What if’s are a waste of time, but what if?’: the remark captures the irony of the exile’s quarrel with history. During the Twenties in my grandparents’ farmhouse in Sussex, a plump old general, who was in charge of the cows, and a colonel, who drove the tractor, used to spend hours at the family dinner table refighting the battle of Tannenberg, gradually corralling all the family silver up their end of the table, to serve as divisions and redoubts in their attempts to change the unchangeable past. ‘What if’ was a game they played with neurotic bafflement, unable to reconcile themselves to the errors that had cost them their country.

The hopeless quarrel with history runs throughout Stone and Glenny’s collection, as does a very Russian sense of helplessness before the unravellings of fate. What Sofia Sergeyevna Koulomnzina says of her father, a conservative member of the Duma, could be said of all the ‘decent’ people of her class: ‘he never rid himself of a certain scepticism, an unwillingness to fight for an issue if he wasn’t absolutely certain that his viewpoint would prevail. The fact is, he wasn’t a fighter.’ In the sudden, peaceful disintegration of the regime in 1917, one can see this ‘decent’ scepticism, this unwillingness to shoot and kill to stay on top, writ large in the whole ruling class. When Pyotr Petrovich Shilovsky journeyed to his estates in Ryazan in April 1917, it did not occur to him to attempt to stop the collapse of authority: he simply came to collect some cash for oats commandeered by the Army Department, and when he discovered that the peasants had driven away his prize herd of cattle, he gave up and took the next train back to Petersburg. In his recollections, he dwells with a kind of paralysed fascination on the spectacle of disintegration that met him when he visited Government House in Ryazan:

The fine furniture, carpets and mirrors had disappeared, and the parquet flooring was bespattered with spittle and strewn with cigarette ends. A few ragged armchairs stood against the walls ... A large number of untidily dressed soldiers with some strange civilians were either sprawling on the seats or rushing about ... We looked at each other in silence.

The sight of an immemorial order collapsing – the new vision of history as an irrational torrent rather than an orderly stream – seemed to rob its defenders of any capacity to resist. For a class used to being masters of their fate, the revolution was a lesson in human helplessness which left them immobilised for the rest of their lives. Count Bobrinskoy, a rich landowner’s son from the province of Kiev, wrote of history as a beast unchained:

There is something uncannily incomprehensible in the outbreaks of the human beast when it gets out of control. The peaceful crofter becomes a robber and a thief; the police lose their nerve; horror and fear creep into the minds of all. The population is immediately and magnetically divided into two sections: the persecutor and the persecuted. Both parties accept their mission and their fate with an unquestionable resolve. There is something fatal, pre-ordained in the events that follow public disturbances. How these disturbances begin and how they end – nobody knows; human power seems to be unable to direct them or stop them.

A cavalry colonel’s daughter, Natalya Sumarokov-Elston, sums up the sense of the Revolution as a shock that left a whole class sleep-walking towards the precipice: ‘it just seemed to me that suddenly one day the soldiers changed, their shirts were hanging out, their belts were round their necks and they were eating sunflower seeds; everything was dirty – all of a sudden, from one day to another.’ This testimony of bafflement foretells the bafflement of their successors – the corrupt and despotic Communist regimes of Eastern Europe – in the face of the rising revolutionary tide of last autumn. It is interesting that the ideological ruthlessness of Communism proved no more effective in galvanising resistance to revolution than the absolutist ideology it destroyed in 1917. In both cases, the will to resist vanished with the recognition that history had turned against them.

Yet the class which had proved so helpless in defending their actual Russia turned out to be extraordinarily tenacious in defending the Russia of their dreams. It was as if only the remembered Russia could rouse them to devotion, not the real Russia they had failed to save. As a child of exile, Metropolitan Anthony Bloom, recalls, ‘we lived Russia, dreamed Russia, waking and sleeping.’ Asked when he would take out French papers, Bloom remembers replying that he wanted to remain Russian and would prefer to die in Russia than to endure eternal exile abroad. Yet all the while, he was aware, as a member of the younger generation (born 1914), that the Russia the emigration had consecrated in its memory was a lost, even false paradise. ‘Everything that our parents remembered about Russia was beautiful, great, virtuous, glorious, honourable – the dark side, the unattractive grey things had somehow vanished from their minds.’

Exile literature never let go of the idea that the true Russia was ‘outside’ – the best literature, the most patriotic love of country, the wisest and most practical minds; what had remained behind was a ‘false’ Russia. Yet somehow the best could only be roused by loss, not by possession. Still, it was a tenacious endurance, a humorous and heroic acceptance of the absurdities of catastrophic social descent. My grandmother met much of the adversity of exile, not with mournful sighs, but, as often as not, with a particular soundless laugh, covering her face with her hands and rocking back and forth, as if helpless before the unending black comedy of dispossession. Natalya Sumarokov-Elston remembers how her father made ends meet in Cannes by reading the meters for the gas and electric company. When Count Sumarokov-Elston, in his gas company uniform, encountered his impecunious friend Baron Prittwitz in tatters on the promenade, he would bow and inquire: ‘How are you, my dear fellow?’ To which Baron Prittwitz once replied: ‘I live like a moth, you know – first I eat my trousers, then my jacket!’

For the generation born into exile, it became impossible to live like a moth, eating up the diminishing store of family memorabilia. Sons and daughters married outside the community, brought their own children up in the languages of exile and slowly substituted the work of assimilation for the work of keeping the old candle of hope alight. Yet if you go to a Russian church in exile these days you see young faces still: the community is reseeding itself, the old claims remain strong.

The social distinctions and snobberies of Imperial Russia survived into the Thirties, but then the tight little clusters of the poor in Clamart and Clichy, and the rich in Passy and Auteuil, began to disperse, and the same was true of all the little communities that gathered around the churches of the diaspora. Pyotr Shilovsky remembers Russian charity concerts at the Park Lane Hotel, at which the men wore their old decorations, the women’s bodices were decorated with what remained of their jewels, and certain families spoke only to certain families. All of this was viable only so long as the surrounding class culture of English society did not make the snobberies of the émigré culture seem ridiculous.

It was among the sons and daughters of fighting age that the calamity of the German invasion of France and then, in 1941, of Russia struck with full force. Some were catapulted into resistance, others into collaboration with the Germans, in a pitiable desire to return to their homeland with the conquering German Army. An extraordinary range of White Russians served in the Axis armies – from the legions of the defecting Soviet general, Vlasov, to the Russki Korpus set up among White groups in the Balkans in 1941. Vladimir Alexeyevitch Gregoriev trained with the Russki Korpus in Yugoslavia and then fought with Vlasov’s army. He remembers that when fighting the Red Army, the wounded would beg to be finished off with a pistol rather than be left to fall into the hands of their fellow Russians on the other side. Many of these young men had never known Russia: they were born outside and their hatred of the Red regime had a simple kind of purity uninformed by contact. Count Tolstoy has made us aware of the crime that was committed by the Allied side when these criminal innocents were handed over to the Soviets and given the chance, at last, to return to the land of their dreams.

Claudio Magris’s novella, Inferences on a Sabre, is about one particularly pathetic White Russian remnant, the Cossacks who briefly occupied north-eastern Italy in late 1944. The novella, written in the form of a letter from one old priest to another priest, remembering the events of the war’s end, is a very affecting and effective reflection on the logic of collaboration among these magnificent warriors who were lured into barbarity by visions of a Cossack homeland in the Thousand-Year Reich. Krasnov is the ataman of these forlorn Italian Cossacks:

There is a stringent logic in the fact that Krasnov threw himself into the arms of fascism, because fascism is above all this inability to discern poetry in the hard and good prose of everyday, this quest for a false poetry, exaggerated and overwrought. But the logic is grotesque, because Krasnov sought to defend adventure, the horseman and tradition through Nazism itself, the deadliest enemy of tradition and adventure, the totalitarian and technological beehive which levels life into a uniformity much more rigid than that imputed to the democracies he despised. By placing his sabre at the service of the Third Reich, Krasnov turned it on himself, against his horsemen, and those ineffable horizons of the steppe.

This taste for the exalted and the romantic, the cult of the lost home, the inability to be reconciled with ordinary life in exile led many young men, including one of my own relatives, to serve in the Wehrmacht and die in their native land killing their own people.

The second great wave of Russian emigration began after 1945. It was composed of surviving Vlasovites, Russian prisoners of the Germans who avoided repatriation after 1945, and Ukrainians, Byelorussians and others who escaped into Western Europe, either when the Germans invaded in 1941 or when they were retreating in 1944. Emigrants from the first, Tsarist wave tended to look on their compatriots from the second wave as Soviets, rather than as true Russians. They were more likely to have come from worker and peasant origins than the first wave, and so snobbery played its part, but more important, their cultural world was different. The second wave was tainted, in the first wave’s eyes, by childhoods in the Komsomol, by hearty summer gymnastics in trade union holiday camps. Worst of all, they spoke that dreadful Soviet-style Russian, harsh and brutal, and packed with the doggerel of newspeak. To say of someone that they were Soviet became the harshest insult in exile, and in many ways the most unfair, since exile was, by definition, the second wave’s choice of revolt against everything Soviet.

Convinced that the Soviet experiment had killed all that was authentically Russian and aware that the ‘true Russia’ of exile was dying out, many post-war children of the first diaspora turned away both from the second wave, and from their Russian past. My father still went to church on Sundays, he spoke Russian to his brothers on the phone, but in other respects he seemed determined, in my childhood at least, to think of himself as the very model of the assimilated Canadian professional. Yet a certain courtliness of manner gave the game away, and in his fifties he returned to the identity of his childhood, and became ever more Russian as he grew older. In The Other Russia, Ilona Ilovskaya-Alberti, editor-in-chief of Russkaya Mysl in Paris, speaks for this post-war generation when she says:

After the end of the war, after all that we had lived through, I turned away very sharply from everything Russian. I had a sad conviction that Russia no longer existed. I mistakenly believed that Russia had turned into the Soviet Union, that the population of Russia had completely absorbed the Communist ideology and outlook and that the Russia which I had once loved, which I believed in, and which had formed my character, remained only in the past ... Russia was ... so to speak ... utopia.

It was with the third wave of dissident and Jewish emigration, beginning in the Sixties and Seventies, that the Russians in exile discovered that the best traditions of Russian intellectual and moral life had survived all along, in heroic adversity, through the darkness of Stalin’s terror. The appearance of Solzhenitsyn’s works in samizdat in 1964 and 1965 first made this clear to Irina Ilovskaya-Alberti: ‘I suddenly understood, with dismay and very deep emotion, that I had made a mistake, that in the Soviet Union there is of course the Soviet system, and there are people who have completely adapted to it, but there is something else too – something living, free – a free soul, a vitality in a kind of Russian tradition, something spiritual and cultural.’ When Isaiah Berlin visited the Soviet Union in 1945, he believed that apart from heroic pre-Revolutionary survivors like Pasternak and Akhmatova, the great Russian intellectual tradition had been extinguished. With delight, he now reports – in Granta magazine – that he was wrong: ‘I have met Soviet citizens, comparatively young, and clearly representative of a large number of similar people, who seemed to have retained the moral character, the intellectual integrity, the sensitive imagination and immense human attractiveness of the old intelligentsia.’

The dissident exiles of the third wave – Brodsky, Sinyavsky, Solzhenitsyn, Maximov, Aksyonov – may disagree about almost everything, may indeed dislike each other in the typical feuding fashion of all émigré intelligentsias, but throughout their internal exiles in the Soviet Union and their external exile in the West, they sustained the tradition of which Russian intellectual culture is most proud: its vision of intellectual and creative life as moral witness. Of the most distinguished of all internal exiles, Andrey Sakharov, Isaiah Berlin remarks that this physicist of the nuclear age, this dissident of the age of television would have ‘been perfectly at home in the world of Turgenev, Herzen, Belinsky, Saltykov, Annenkov and their friends in the 1840s and 1850s’. The same could of course be said of Isaiah Berlin himself, and if this is so, if internal exiles and expatriates can now recognise each other as common kin of a Russian intellectual heritage which Stalin did not succeed in destroying, then the old schism between Russian and Soviet, internal and external cultures may be on its way to healing. Of all the long-term effects of Gorbachev’s accession to power this is the least discussed: the reunification of Russian culture itself, and the consequent return of the Russian heritage to the common European storehouse.

The Other Russia is an extremely valuable source-book for the exploration of these themes. It is the first study, to my knowledge, which incorporates the experience of all three waves of Russian emigration, and the first to do so in the often inimitable language of the emigration itself. Oral history enables us to catch a whole world view in a single casual aside, as when the daughter of the last governor of Volhynia remarks in passing: ‘Jewish friends were out of the question, of course.’ What more perfect encapsulation of the blindness of an élite paddling at the lip of revolution than Madame Rodzyanko’s overheard remark in the early days of the March Revolution: Lenin, qui est Lenin? Est-ce-qu’il est gentil? Finally, how interesting a sign of the divided cultural loyalties of a whole class that the Dowager Empress should resort to French when expressing her anguish at leaving her native land: Mais je ne puis pas partir. Je ne veux pas quitter la Russie.

What is disappointing about The Other Russia is that it provides so little by way of context. Their voices are disembodied: the editors do not describe how they look, how they live and, by deleting their own questions, deprive us of the sense of how they converse. The introductions to each section of memoir have all of Norman Stone’s proverbial dash and vigour, but they are written in the manner of his hectic journalism and lack the scholarship of his books. The dramatic events which divided the émigrés in the Thirties – Kutiepor’s disappearance, General Miller’s abduction by Soviet agents, Plevitskaya’s trial for her part in that abduction – are missing from Glenny and Stone’s introduction. The Other Russia will not help us to understand anything about the politics of émigré groups. Better to turn to Robert Johnston’s excellent New Mecca, New Babylon: Paris and the Russian Exiles 1920-19451, which has languished in neglect, just possibly because it appeared from a Canadian university press. Both Johnston and Robert Williams’s Culture in Exile: Russian Emigrés in Germany2 fill in what is missing from The Other Russia, not only émigré politics, but the émigré press, especially Posledniia Novosti and Sovremeniia Zapiski, which published Nabokov, Berberova, Khodasevitch, Tsvetaeva at a time when Western arbiters of literary taste – from Aragon to Gide, from Wells to Shaw – were celebrating Gorky and Co as the dawn of a new era in literature. Marc Raeff’s forthcoming Russia Abroad: Cultural History of the Russian Emigration3 can also be counted on to fill in the cultural and historical context which the editors of The Other Russia have failed to place around their symphony of voices from Russia’s mournful but heroic heritage of exile.

Send Letters To:

The Editor

London Review of Books,

28 Little Russell Street

London, WC1A 2HN

letters@lrb.co.uk

Please include name, address, and a telephone number.