A bolt-eyed, blue-shirted, shock headed hatless man ... ‘Mrs Woolf? ... I’m Graves.’ He appeared to have been rushing through the air at sixty miles an hour and to have alighted temporarily ... The poor boy is all emphasis, protestation and pose. He has a crude likeness to Shelley, save that his nose is a switchback and his lines blurred ... The usual self-consciousness of young men, especially as he threw in, gratuitously, the information that he descends from Dean, Rector, Bishop, Von Ranke etc etc, only in order to say that he despises them. I tried, perhaps, to curry favour, as my weakness is. L was adamant. Then we were offered a ticket for the Cup Tie, to see which Graves has come to London after six years. No, I don’t think he’ll write great poetry: but what will you?

His mother was indeed a Von Ranke; his Anglo-Irish father famous in his time for many things – including the authorship of an immensely popular song, ‘Here’s a good health to you Father O’Flynn’ – but above all for being upright and honourable, a great gentleman of the old school. The eldest son inherited the mysterious gift of producing an instant best-seller; Molly, one of the daughters by a previous marriage, became a famous water-diviner. When the treacherous Robert produced Goodbye to all that, the long-suffering father, who had supported and encouraged the son for many years and received in return nothing but patronage and contempt, riposted at the age of 84 with his own autobiography, To return to all that. Alas, this spirited gesture merely revealed the impotence of age, the powers irrevocably lost to the killer progeny. The son’s book was a runaway success, the father’s remaindered.

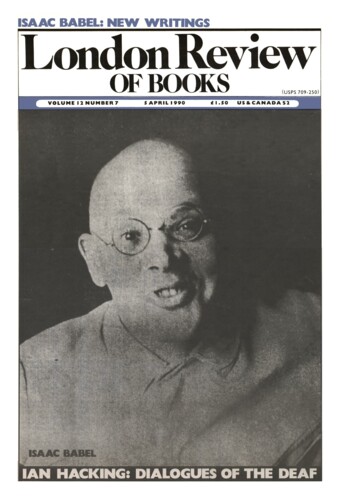

Not many famous writers can be read in terms of their immediate ancestry: Graves is an exception. Powerful wires were in some way crossed or the terminals wrongly connected: the result, an assortment of literary skills bordering on genius, but so heterogeneous that they get blurred, as in Virginia Woolf’s description. Her impression of Graves in 1925 is not quoted by his nephew, who has now brought out the second volume of a totally absorbing biography, but his plain, sensible, even-tenored, shrewd account of the most famous member of a big, effective clan bears out pretty well the sense implicit in her lightning sketch. Richard Perceval is the son of John, Robert’s youngest brother, who was also snubbed, patronised and cold-shouldered. Richard Perceval has written excellent studies, admirably researched, of A.E. Housman and of the Powys brothers, but now is the time to strike a blow for father and get revenge on uncle. I don’t suppose for a moment that any such intention was in Richard Perceval’s honourable mind, but in a sense he only has to tell the story, making use of the family archives and private letters, for the revenge to be a tolerably complete one.

The story is Graves’s long affair – 1926 to 1939 – with Laura Riding, and his eventual dismissal, or escape. No doubt it was both, yet it seems likely that if this extraordinary woman, a Circe in modern dress, had not set about enchanting a new Odysseus, a brilliant American called Schuyler Jackson, Graves might have remained indefinitely in her thrall. She had, of course, a whole stable of obedient creatures who submitted to her powerful charms, but Jackson turned out to be a different sort of admirer altogether. Not a masochist but a sadist, he collaborated with Riding in her ritual destruction of his own wife Kit – a ceremony carried out in the sinister environs of a New England farmhouse with the other disciples in submissive attendance – but then asserted himself even before their marriage as her equal, even as the dominant partner. Jackson, not Graves, was the hero of the saga, taming the goddess who had denounced his own wife as a witch, and reducing her, at least temporarily, to a meekly spousal role.

Graves, for whom Riding was the White Goddess – ‘she was his muse and he loved her and abandoned himself to her,’ as one of the other disciples touchingly remarked towards the end – would have been horrified by such an outcome. But perhaps she secretly hankered for such a relationship, and to be ‘mastered’ through love? Love itself, as well as admiration, she could certainly never have enough of, although sex was something to be made use of, and discarded as soon as the victim was under control, as happened in the case of Graves. Her father, an unsuccessful Jewish businessman, had been born in Austria, and she had been brought up poor in New York, though well-educated. A rapid marriage to a fellow student resulted in an abortion which may have left her unable to have children; there was a powerful Yiddisher momma inside her which displaced itself on the family of worshippers she both needed and resented. After getting in touch with Graves on literary business, she rapidly took in his vulnerability, and that of his marriage. Nancy Nicholson, as she still called herself, daughter of the well-known RA, had married Graves after the war and lived with him on hand-outs from their families, trying to combine a family of four children with her work as an artist. Relations with her husband were strained, and she welcomed the Riding incursion, expressed to her through feminist sympathy and solidarity. Riding (she had coined the name for herself) always had a way with children. Presently they were joined by a young Anglo-Irishman called Geoffrey Phibbs and began together what they called the ‘four life’.

It had a strong element of the grotesque, for they all took it very seriously, with intense talks and conjurations in the manner of Anthony Powell’s The Kindly Ones with its highly diverting mumbo-jumbo in which ‘the image of the all is the godhead of the true.’ Such associations were part of being enlightened at the time, and Graves’s bible had always been The Way of All Flesh, Samuel Butler’s call to freedom from parental bonds of respectability and convention. Lawrence and Gide were also in the air. But neither Graves nor Riding strike one as being in any sense in a fashion: rather, they needed to feed on each other in a businesslike way, so that each could realise through the other not only a private myth but the ambition to be a new and great sort of poet. Graves also had a more obvious problem:

A long time ago I told my mother

I was leaving home to find another,

as Auden puts it. Amy von Ranke had great merits as a woman, but these, naturally, were of no help to her eldest son, except in terms of support and finance, nor was the more fashionably emancipated life-style offered by Nancy Nicholson. Both as man and as writer, Robert Graves was stalled, paralysed by powerful internal forces which pulled all ways and cancelled themselves out. He had to find a new prison in which he could feel liberated.

Did Laura Riding sacrifice her own talents to build up his? It could easily be seen that way, though both would have scorned the idea of any such exchange, finding in themselves ‘a joint desire for the survival of ancient truths’, and holding steadfast to their ‘covenant of literal morality’. The first sign of freedom, change of heart, new styles, was the symbolically named Goodbye to all that, but before that success something near disaster had befallen the ‘four life’ system. Nuclear affections had reared their heads: Phibbs and Nancy were threatening to run off together. Laura’s reaction was Dostoevskian, seemingly spontaneous. After a marathon talking session in which she and Robert vainly tried to bring the deserters to heel, Laura sat herself down on the window-sill of their fourth-floor Hammersmith flat. ‘Well, goodbye chaps,’ she said – an endearingly out-of-character comment from so delphic a presence – and let go. Robert rushed down the stairs, and distractedly realising he was too late, threw himself out of a third-floor window.

Both were alive when picked up: Robert hardly injured, Laura with pelvis and vertebrae broken in several places and spinal column twisted at right angles. But could she, or he, really have fallen so far, or did distance grow in telling? – in Gravesian circles ordinary veracity was not important compared with the survival of ancient truths. At any rate, Laura was saved by the promptness and efficiency of Robert’s elder sister Rosaleen, a qualified doctor from the Charing Cross Hospital, who eventually got the most famous spinal surgeon in England to put things right. Present herself at the operation, Rosaleen was impressed by the great man’s remarking that it was rare to see the spinal cord exposed and bent in this way. He then bent it back. Far from being grateful at being saved from permanent paralysis, Laura merely observed, when Rosaleen timidly asked her if she would like to meet Mr Lake the surgeon: ‘There is no Mr Lake. I invented him.’ But I fancy this may have been New York Jewish humour.

Humour was not apparently her partner’s strong suit. Having caused the maximum hurt to the feelings of wife, friends and family, Robert felt that the world owed him a garden of Eden in which to recover, and he and Laura proceeded to find one at Deya in Majorca. Here Laura rapidly built up another menagerie of worshippers, kept in order by Robert’s reminders that they were in literal attendance on a deity, the repository of the whole principle of love. Some were clearly not impressed, but nonetheless found Laura an extraordinary and fascinating woman. She inherited, however, her father’s lack of business flair. Her ambitious attempts to build a road and make a resort brought them to the edge of bankruptcy, from which they were only saved by the success of I, Claudius, a book which Laura permitted Robert to write, while refusing to discuss it except in the most contemptuous terms. It is possible to wonder whether the pull of the novel, its undoubted feat of impersonation, may not come from Graves’s own undercover sense of himself as the Emperor who took refuge in being a clown from the machinations of the Roman powerhouse – in his own case, from family background and from Laura herself. There is a suggestion of maniac cunning in Graves’s blundering progression, as if he needed a sardonic refuge from being ‘understood’ and managed by powerful mother figures.

There was also his boy scout side, the pleasure of doing and making things as troop leader in a little colony run by himself, responsible only to Matron. Here both his German and his English inheritance produced a potent and by no means always agreeable mixture of styles and showings-off, as if Stefan George had founded his clique not in a German castle but an English public school. The ‘discourse’ of Goodbye to all that is uneasy and aggressive, unstable while stiff-lipped-boastful. Graves had his Hemingway side too, the gender-muddled patriarch telling stories of how he knocked them all out: a huge Swede in Deya who came swinging at him ‘without any science’ was, according to the Graves account, seen off without trouble by a single straight left. And in spite of his undoubted awe of, and need for, Laura Riding, he remained like a small boy wholly fascinated by himself, and with no time for other writers or poets such as Yeats – an obvious rival in magical charisma. The secret of his mature poetic skill was to marry, at least in the best poems, this burly Narcissus persona with a generalising authority, wonderfully dry and sinewy, which gives the reader a temporary sense of being the friend, confidant, even equal, of a modern Propertius or Catullus.

But in exercising her powers over others does the goddess forfeit them herself? Both Graves and Riding might have felt so, the one with secret glee, the other with open resentment, for all their reactions were obviously ambivalent. T.S. Eliot courteously but firmly refused her poems and articles for the Criterion, and he was a shrewd judge of the poetry of his contemporaries. It is true that Michael Roberts’s Faber Book of Modern Verse, which came out in 1936, gave her as much space as any poet; but, even though it contains arresting things, her verse is curiously unmemorable and has not worn well. She and Graves shared the feel for a classic turn, a weighty clarity and lapidary line, but which one it came from is not easy to say. Close partnership blurs such distinctions, and it was Graves, like Wordsworth, who won out in the end. She claimed to have made him think straight, but where his lines are plain and deeply scored, hers are often portentous. A poem like ‘Nor is it written’ has many Gravesian lines, but the overall impression is more like Conrad Aiken and other American poets of the time than Graves’s own emphatically English idiom.

But it may well be that the idea of the ‘cool web of language’, which Graves worked up into one of his most memorably articulated poems, came from Laura Riding herself.

Children are dumb to say how hot the day is,

How hot the scent is of the summer rose,

How dreadful the black wastes of evening sky,

How dreadful the tall soldiers drumming by.

But we have speech to chill the angry day,

And speech to dull the rose’s cruel scent.

We spell away the overhanging night,

We spell away the soldiers and the fright.

There’s a cool web of language winds us in.

That notion was beginning to be around in linguistic and philosophical circles at the time. Schuyler Jackson, who had himself been a poet and the dazzling Princeton pal of Tom Matthews, the writer and Time journalist friendly with Graves and Riding in Majorca, remarked when shown the Riding poems: ‘But this isn’t poetry, it’s philosophy.’ When she went to live with him, Riding announced that she was giving up poetry for philosophy, as if, having created one poet, she could now drop that sloppy business and get back to what mattered. The beautiful articulation of Graves’s poems may have owed as much to her as to the sound Classical education that Charterhouse had given him, but their attempts at active collaboration were a failure. His biographer rightly observes that A Survey of Modernist Poetry (1927) was something of a pioneer work in the vein of Graves’s contemporaries, I.A. Richards and William Empson, but the pair’s dismantling and reinterpretation of Shakespeare’s sonnet ‘The expense of spirit in a waste of shame’ shows their peculiar sort of wilfulness running mad, however much they were on to what later became the ambiguity principle. Other joint ventures failed to find a publisher or remained embryonic, like the potboiler A Swiss Ghost, which they began together in Lugano, and which Laura dismissively handed over to her partner at the final break.

‘We shall go mad no doubt and die that way’ ends ‘The Cool Web’. Laura Riding had certainly rescued her partner from breakdowns, and perhaps from more deep-seated mental problems. It is true that he dramatised them, as he did his war experiences in Goodbye to all that, but they seem to have been real enough. The mother and the mixed-up provenance was no help either. An uncharitable verdict might find Graves German in the bad sense – all broodings and life-mysteries and spiritual rebirths – and English in the bad sense too: snob and prig, schoolboy and puritan. The whirligig of time brought its habitual revenge when his own children, whom he had not notably cared about when they were young, began to exploit him and cause him anxiety: his daughter Jenny, who became a dancer, acquired both clap and an unsuitable lover at the age of 17. He continued to despise his younger brothers and to be ungrateful to his elder sisters, who had given him every sacrifice of practical affection. He knew all this and no doubt repented in his own way. When he left Laura, his wife Nancy hoped to have him back, but he had found someone else, who had become all the dearer to him from Laura’s disapproval. Rather touchingly, when he wrote a goodbye letter to his wife he assured her that her successor would also be ‘a lady’.

Send Letters To:

The Editor

London Review of Books,

28 Little Russell Street

London, WC1A 2HN

letters@lrb.co.uk

Please include name, address, and a telephone number.