In Jerusalem, stones can do the work of flowers – at Jewish cemeteries, that is, where flowers on graves are taboo. To show you have been at a graveside you place a pebble or a chip or a rock on the gravestone. Then you inspect the rows nearby to see how their little piles measure against yours. A spirit of sporting rivalry adds a little spice to a sad occasion, and people play, I think, according to the rules. They don’t pile stones greedily; one a piece and no cheating. It’s a matter of respect.

Over by the Old City ‘Absalom’s’ tomb has suffered a different kind of attention. Pilgrims threw stones at it to punish Absalom for being such a bad son to their favourite Biblical hero. Eventually the whole rock-cut façade disappeared into a pile of stones, out of which the archaeologists dug it. Today no one throws a stone at ‘Absalom’ any more. There is more sympathy, perhaps, with long-haired, rebellious sons, and there are more obvious targets for stones.

Unlike stones, which are everywhere, water in Jerusalem is an illusion or a missed opportunity. It is not there, though it looks as if it might have been. The hills on which the Old City rides swell like gentle waves. The corner of Herod’s wall facing the desert looks from below like the prow of a great ship looming over your dinghy. The city could be sailing into the desert if only some flood-tide of cleansing water would lift it off its heavy bed of stone. Yet the pink, warm stone of the old houses radiates comfort in the evening light, and when the city was divided by a border, even the biscuit-coloured stones of Sultan Suleiman’s Old City wall looked more domestic than martial as they stood guard over their secrets, while we looked on from the Israeli side of No Man’s Land which separated our stones from theirs.

My feelings about stone in the city have fluctuated wildly between love and hate. I have loved its colours, its belonging, its domesticity. I have hated its dryness, its nakedness, its excretion of deathly dust. Looking at Herod’s massive ashlars in the Temple wall, I am as oppressed by their weight and downward thrust as if I lay beneath them: yet in front of a simple, rock-cut tomb of the same period I am won over by its sanity, its purity, its domestication of death.

I have never felt as passionate about water. After I discovered that the foaming mountain stream one sees from the picturesque railway link to the coast is actually processed sewage, I gave up on the romance of flowing water. It is suspiciously idolatrous, more suitable to pagan shrines by caves and green groves than it is to Jehovah, who likes deserts for their emptiness and clear vistas.

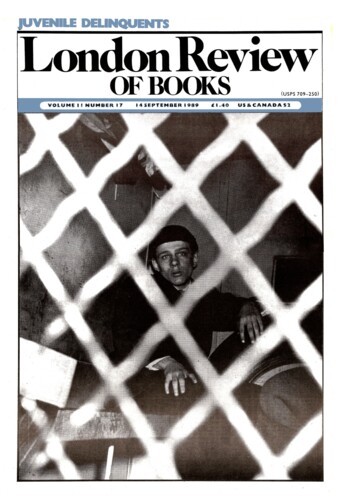

Stones in Jerusalem seem to accompany thoughts of death and transience. Yet they also break windows. Once they were thrown in protest mostly by orthodox Jews, who kept their neighbourhoods free of cars on the Sabbath by accurate lapidation on the approach roads. But the Sabbatarian stones have since been outnumbered by those of the intifada.

It was Brecht who – in Jerusalem, of all places – introduced me to the politics of stone and water. It happened before the intifada, only just, when I took a Hebrew University theatre class to East Jerusalem to see an Arabic production of Brecht’s lehrstück (learning play), The Exception and the Rule. The company was El Hakawati, an energetic Palestinian agit-prop theatre whose colourful plays tended to start at the village well and end with a scene of universal cataclysm. They had adapted Brecht’s 1930 play, and were showing it in Arabic to audiences of young people, mostly from East Jerusalem schools.

The play was written in order to educate Communist party cadres in the logic of revolutionary situations. It takes place in an Asia readers of Tintin would recognise and deals with the fortunes of an evil oil-prospector, the Merchant, and his guide, across the great desert, the Coolie. The stone which caught my attention plays a prominent part in the climax. The Merchant and the Coolie are lost and have apparently consumed all their water. On his side of the stage, the Coolie, miserably abused, considers his dilemma: he has succeeded in hiding an extra water bottle. If he drinks and saves his own life the Merchant will die and the Coolie will be accused of his murder. But what obligation does he have to his evil employer? On the other side of the stage the Merchant drinks some water he has never revealed to the Coolie, certain that, if he sees, the Coolie will kill him for it. The Coolie makes his decision, gets up and with arm outstretched offers the Merchant his water. The Merchant thinks the water bottle is a stone, takes the gesture for a threat and shoots the Coolie. In a trial at the end of the play the Judge concludes that the Merchant acted reasonably. He had every reason to expect the Coolie to hurt him and no reason to believe that he would give him his last drop of water. Verdict: not guilty.

I was well-schooled in that Palestinian theatre. I had seen many of their plays, and was well-trained in the discipline of seeing myself played as a grotesque, sinister, sometimes absurd tyrant. I did not expect from them either a hopeful or a balanced picture, least of all one that flattered me. However the metamorphosis of water into stone troubled me and has continued to do so now that stones are exchanged for bullets in the streets of Gaza and the towns and villages of the West Bank.

Is that me, the warped greedy man who undoes Moses’s miracle in the desert and turns water into stone? And who is the victim of my ill-will? Who is that Pragmatic Samaritan who offers me water to save his neck? Is that a true image of the Palestinian to whom I am bound in this landscape?

Gestures seen on the stage take on gigantic proportions. They grow with time. The outstretched hand with its water-stone would not leave me alone. I debated with it in my dreams and, in the bus as I rode to work round the edges of East Jerusalem, I mentally queried the modestly dressed schoolgirls and the casual labourers waiting to be picked up for a day’s work. What would you hold in store for me if we were lost like that in the desert? Water or stone?

In some ways I am an unenlightened Israeli. I find it hard to cure myself of a low-grade fever otherwise known as the victim’s ague. I can’t rid myself of the suspicion that someone is waiting to mug me as I turn the corner. I know the evidence is currently against me and that I am the source rather than the object of violence. I also know how salutary it is to practise seeing yourself in the harsh light of the other’s grievance. But I will not fall into the trap of denying or belittling my own peril because I take the other’s seriously.

This explains how my view of the outstretched hand with its water-stone veered between assent and scepticism. I was captured by Brecht’s rhetoric, his characteristic mixture of cunning and pathos as he lays bare the narrow choice of the oppressed. I also suspected its application of kitsch, of a fake pathos, and suspected it of missing the point of where Jew and Arab are here and now.

I do not make the mistake of holding the Palestinians to my version of reality. Their iconography of national resistance is often totally convincing to my eyes: for instance, their image of staying put on the land, a bent old porter carrying on his back the domed, minaret-marked outline of Jerusalem. That is an emblem of a living reality. It is undeniable. Not so the hand offering the water. That is not undeniable, because it fails to grapple with the reality of almost a hundred years of rivalry and conflict. Even today, after the change in PLO policy, put it on a poster and no one would know what it was.

In 1938, Zionist ‘Palestinians’, as they were then called, acted the same gesture on an improvised stage at a kibbutz near Haifa. That was where Brecht’s lehrstück had its improbable world-première, performed by refugees in unfamiliar Hebrew before an audience of chess-players turned farmers who were to be taught a lesson in the tactics of the class struggle. With the benefits of hindsight, the clarity of the play’s Marxist analysis seems surrealistic. It is theatre of the absurd in the light of what was really going on: Hitler’s assault on civilisation and, in Palestine, the increasing armed strife between Arab and Jewish neighbours.

An escapist pathos unites the two Palestinian plays, that of the Zionists in 1938 and that of the Arabs half a century later. The former indulged in a nostalgia of the class struggle to avoid the reality of their neighbours’ grievance and Europe’s madness. The latter, bringing Brecht into Palestine, take refuge in an allegory which demonises their enemy and absolves them of responsibility for their own fate.

Today Israelis are divided between the two minorities of those who see only the stone and those who see only the water, and the majority who astigmatically see both stone and water superimposed on each other, moving and merging like a mirage in the crackling heat. Some, currently the leadership, reach for the gun. Others would try the water, if it is there. Even if you have to drop your guard to drink. Even if it tastes of stone.

Send Letters To:

The Editor

London Review of Books,

28 Little Russell Street

London, WC1A 2HN

letters@lrb.co.uk

Please include name, address, and a telephone number.