In February 1981 Mrs Thatcher made an ecstatic pilgrimage to Washington to commune with the new President, Ronald Reagan, about such then modish topics as supply-side economics and the evil empire. Hugo Young recalls the ‘patronising astonishment’ with which her Foreign Secretary, Lord Carrington, witnessed this effusive display. Asked by a colleague, on his return, how the visit had really gone, Carrington replied: ‘Oh, very well indeed. She liked the Reagan people very much. They’re so vulgar.’

The story illustrates the major problem of writing a biography about Margaret Thatcher: personally, she is neither nice nor interesting. She has immense energy, remarkable tenacity and stamina, and a good brain. But she has a shallow mind, little imagination and an immense, bullying ego. As she goes ramping on and on and on through these pages, just as she has gone ramping on and on and on through the last decade of British life, it’s hard not to feel a sort of appalled boredom. There is, moreover, no end to her presumption: to the already notorious quotes one can add another culled by Young, who finds her measuring ‘my performance against that of other countries in the real world’. And while it contributes something to one’s assessment of, say, Macmillan to know that he sought solace in his private hours with the works of Livy and Jane Austen, what can one say about someone who, after spending much of her day ranting at her ministers, her civil servants and the Opposition about the evils of socialism, likes to relax, as her confidant, John Vaizey, put it, by ‘exciting herself with books about the horrors of Marxism’. ‘At the moment I’m rereading The Fourth Protocol,’ she happily tells a journalist. Rereading. Jonathan Miller talks of her ‘catering to the worst elements of commuter idiocy’ and one can see what he means.

Hugo Young is the best political journalist writing in Britain today, and One of Us is likely to be the standard work for quite a while to come. Some things were new to me. I hadn’t known that as Minister for Education under Heath, Mrs Thatcher had fought to preserve the Open University, or that she regretted her measure to abolish free milk in schools (characteristically blaming the Civil Service for her mistake), or that she had fought against the idea of abolishing the rates when it was proposed by Heath. It was also something of a shock to hear that she had toyed with the idea of inviting Roy Jenkins back from Europe to be Chancellor of the Exchequer in 1979. Otherwise it is pretty much the story as we know it: one can, reading Young, get the feeling that one is reading ten years of the Guardian again. It is very much a political correspondent’s book, not only because there’s far more on political scandals like Spycatcher and Westland than on the economic factors which determined the Government’s life, but in the way that insiderish factors are sometimes rather questionably assumed to be the ones that count. Young seems to think that the 1987 Election began to tip away from Labour when Kinnock was caught having telephone chats with the Australian lawyer acting against the British Government in the Spycatcher case. Yet the polls do not suggest that this fact ever registered very widely outside Westminster. What they do suggest is that the long and blazing row over defence policy staged by the Alliance was far more important, since it had the effect of shedding a merciless light on Labour’s weakest point, and was all the more difficult to deal with because it was taking place within another party.

Young is not at his best with opinion polls and electoral data. Examining the 1987 result, for example, he speaks of the rise in the Tory share of the working-class vote and the fall in its share of the middle-class vote as being the products of eight years of Thatcherism. In fact, this class de-alignment had been visible as a trend (and extensively written about by academics) for several years before the advent of Thatcher. The real question is not whether she has pulled workers over to the Tories but whether Thatcherism is not in part the product of an already de-aligning working class.

One or two things seem to have eluded Young. He mentions the young Margaret Roberts’s election campaign in Dartford in 1950, but neglects the best part of it. Ms Roberts insisted throughout the campaign that she would win. As they neared the last lap, her agent advised her to drop this line. She had, he said, fought a bonny campaign, but the Labour majority was 19,000 after all, and it would be best not to risk looking ridiculous in a few days’ time. Only at that stage did it emerge that Ms Roberts was so full of naive self-belief that she really did think she would win, and wouldn’t hear a word more of this defeatist talk. She lost by 13,600.

The second point is far more significant. Young notes that Mrs Thatcher has developed a close relationship with the large Jewish component of her Finchley constituency, and remarks that ‘she had special need to do so, since shortly before her first election’ – in 1959 – ‘Tory forces had combined to exclude Jews from membership of the Finchley Golf Club. This presented her with no difficulty.’ This is to gloss over a critical moment in Mrs Thatcher’s career. Golf-club anti-semitism is, even today, a fairly common part of English life and the Finchley row of 1957 took the not unusual form of the club committee which excluded Jews being largely made up of Tory worthies wearing, so to speak, their golfing hats. The Liberals took up the issue (ultimately righting it), and in 1957 the first Liberals gained election to the Finchley and adjoining Friern Barnet Councils.

The arrival of Mrs Thatcher, and her golfing husband, in Finchley in 1959 did not, however, see the end of the matter. In 1961 the Liberals, riding the wave of Jewish protest, attacked every ward in Finchley for the first time and in 1962 they won every single ward there, as well as three of the five Friern Barnet wards. It was suddenly clear that Mrs Thatcher was in real trouble. In 1959, she’d been elected with a majority of 16,260: now the Liberals had polled 51 per cent right across her constituency. Worse still, in 1963 the Liberals repeated their clean sweep: they now held 19 of the 24 seats on Finchley Council. Six of the 19 were Jews, including the new mayor and deputy-mayor, and there was just one issue – ‘the Jewish question’, as it was baldly called. Feeling was running extremely high – there was a nearly 60 per cent poll – and it seemed possible that Mrs Thatcher’s political career would be abruptly terminated in an angry wave of Jewish anti-Tory protest. Finchley, wrote Bernard Donoughue in 1964, ‘was the Liberal Party’s greatest and most publicised hope of “another Orpington” in the South-East of England’. The Liberals even arranged two special TV campaign appearances for their candidate, John Pardoe.

All of this must have induced a fair amount of panic in a young Tory hopeful, a woman at that, who had only found this winnable seat after a nine-year search. Mrs Thatcher can have been in no doubt that if she lost Finchley she would never get another chance; and the news that the Liberals had made her their top target in the whole country, drafting in a huge team of outside helpers, can hardly have helped her sleep at nights. But somehow, in the course of 1963-64, the tide was turned. No biographer has ever told us how Mrs Thatcher managed this, or even the exact nature of the role she played in the row, but Young is surely wrong to dismiss the whole incident with the statement that the situation ‘presented her with no difficulty’: mediating between enraged Jewish erstwhile supporters and the traditional Tory worthies on the 19th green can hardly have been easy, and it’s not certain that Denis would have been altogether an asset. All we know for certain is that a new Tory agent was hired in 1962 with the mission of rebuilding the constituency party organisation almost from scratch and that in 1964 Mrs Thatcher managed to hold the anti-Tory swing among Jewish voters down to 20 per cent. She has taken extreme pains never again to find herself on the wrong side of the Jewish vote.

Mrs Thatcher comes from the sort of provincial suburban background in which a mild anti-semitism has traditionally been quite pervasive, but one of the most attractive things about her is the entirely open-hearted way she has related to the Jewish community. This is not contradicted by the Foreign Office having its own line on the Middle East and clearly stems from something far deeper than local electoral convenience – Mrs Thatcher instinctively warms to the Jewish nouveaux riches of North London and seems to see Judaism as an exemplary religion of capitalism. The Chief Rabbi, Immanuel Jakobovits, has done much to encourage this symbiosis: indeed, he seems to have the ambition, as Young puts it, of becoming ‘the spiritual leader of Thatcherite Britain’. He has certainly acted more like the old-fashioned head of an established church than has Archbishop Runcie. Not only are his sermons Samuel Smiles homilies, attacking trade unions, preaching the gospel of work, advising the blacks to pull themselves up by their bootstraps like the Jews, but he has strongly attacked the Anglican document ‘Faith in the City’ as being, in effect, a charter for welfare-scroungers and the work-shy. This being Thatcher’s Britain, these sentiments have earned him a place on the Honours List.

Thatcherism has seen the Jewish identification with Labour stood on its head. In the old days a Jewish Tory MP, if not quite a contradiction in terms, was likely to be a Sir Gerald Nabarro – converted away from his Jewish faith and becoming a sort of caricature of the Tory squire. In the Seventies this changed sharply. Harold Macmillan’s alleged retort on seeing the first Thatcher Cabinet list – ‘there are more Old Estonians than Old Etonians in this government’ – must have been symptomatic of what many Old Guard Tories felt. There was a record Jewish presence not only in Mrs Thatcher’s Cabinet – including, at its peak, Joseph, Lawson, Young, Rifkind and Brittan – but among those on whom Mrs Thatcher leant for private advice: Joseph, Lawson, Alfred Sherman and the Saatchi brothers. Able young Jewish MPs (and there are now quite a few on the Tory benches) were natural recruits to the Thatcherite cause, not only because they often came from market-oriented careers, but because they were free of all ties to the Tories that Thatcher was displacing.

Resistance to this historic change in the composition of the governing élite has been happily muffled, but one can see something of the strain between the old guard and the new in the relationship between Nigel Lawson and Willie Whitelaw: the brash young financial journalist and the hereditary landowner. Whitelaw regarded Lawson as fast, flash and ‘thoroughly unsound’. In Young’s words, of Whitelaw’s ‘myriad managerial tasks, keeping Lawson out of high places had not been the least important’. Thatcher was, however, determined to get Lawson to the Treasury. She finally overcame Whitelaw’s opposition, but Whitelaw went around making it clear that he could never be comfortable with the fact. ‘Nigel Lawson is unfortunately almost entirely without friends,’ he was wont to remark. ‘I have therefore made a very conscious effort to become his friend. People tell me this is a doomed enterprise.’ It is in the nature of their being Jewish that men like Lawson have to get used to people like Whitelaw thinking, in the famous phrase, that they are ‘too clever by half’. Later, of course, Whitelaw was to stage a long and successful rearguard action against Lord Young being allowed to take over the chairmanship of the Tory Party. Again, the terms of the dispute were revealing: Young, the millionaire property-developer, arguing that since the Tory Party had an annual turnover of only £5 million, any really businesslike minister could run it in one day a week, Whitelaw retorting that it would not be proper for a Minister of Trade and Industry to be soliciting Party contributions from those he was supposed to be regulating.

All of this was, however, pretty coded stuff. Only with two members of the Government, Leon Brittan and Edwina Currie, did their Jewishness become a cause for comment. In their very different ways, these two ministers had personalities which rubbed their colleagues up the wrong way, a fact which was, in the usual mysterious manner, put down to their Jewish origins. When they slipped up, the Labour Party, as if sensing the strain, was in both cases able to hound them out of office. (We have just seen Paul Channon, the Transport Minister, brazen out the constant run of transport disasters, thanks to solid backbench support. Would it have been the same if he’d been Jewish?) One Tory backbencher greeted Thatcher’s sacrifice of Brittan with the furious demand that his replacement should at least be a ‘proper red-faced, red-blooded Englishman’. Brittan, secure in his European appointment, has now got his own back with his Westland disclosures. Despite her conversion from Judaism, similar mouthings about Mrs Currie could recently be heard from certain red-faced, red-blooded Englishmen on the Tory backbenches.

Young’s biography does not, unfortunately, directly broach any of the major analytic questions about Thatcherism. But three are inescapable. From what did Thatcherism originate? What distinguishes it from traditional Toryism? And will it work?

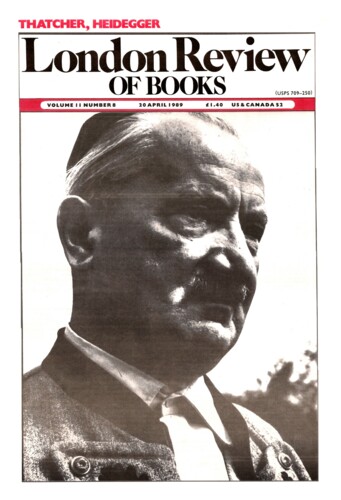

Mrs Thatcher is keen that we turn back the page to those inter-war figures, Ludwig von Mises and Friederich von Hayek, and see things through their lens. Ironically, in understanding Thatcherism the best place to start is with the collapse of German conservatism in the Thirties and the concomitant rise of Nazism. Nazism grew in response to two major threats: the exploitation and immiseration of Germany at an international level, and the threat of the Left at the domestic level. German conservative voters not only felt terrified by these two threats but, losing all confidence in the ability of the traditional ruling class to protect them, turned instead to the radical petit-bourgeois leadership of the Nazis. The result was the re-formation of the old conservative bloc under subaltern leadership: quite literally, the old Junker class and its generals were now commanded by a former corporal.

If we strip this model of all the ideological baggage which attaches to Nazism, what we see is that the last resort of conservatism faced with a domestic and international crisis is its own social re-formation. In this model, the old structure of the conservative coalition suffers a radical inversion, so that the leadership is seized by a tough-minded parvenu group willing to take extreme measures to save the day. Typically, the old leadership group proves socially incapable of taking its rivals seriously enough, and either underestimates the parvenu challenge until it is too late, or nourishes the illusion that it will get rid of the parvenus after a year or two. The old group of vanquished notables then either quits the field altogether or is grumblingly re-integrated into the coalition at a lower level, on terms set by the new, upstart leadership. However, since the leadership of this group is socially so unnatural, it needs to shore itself up by a greatly strengthened leadership principle and a sweeping centralisation of command. Typically, too, the Left also underestimates the parvenu challenge: in the German case, not only was the Left locked in fratricidal battle, but some Communists even thought that the Nazi seizure of power would ultimately benefit the revolution.

Thatcherism is not, of course, Nazism; and Britain has not had to face a crisis remotely as grave as Germany’s after 1929. But the model is clear enough, and clearly enough it fits. The two dangers threatening the British middle classes – relative decline at the international level, the trade-union challenge at a domestic level – were, however, experienced as being truly acute only by a fraction of the old Conservative coalition. This fraction was hardly uniformly petit-bourgeois but it did, perforce, have to look to outsiders within the Conservative camp and it did work by centralising command and erecting the leadership principle to unparalleled heights.

Faithful to the model, we find that the reformation of the Conservative bloc under Thatcher took many of its victims unawares. Over and over again in Young’s pages, the Priors, Gilmours and Pyms reproach themselves for having comprehensively misconstrued and underestimated the advance of the whole Thatcherite phenomenon. Whitelaw, early on, reflected that ‘being a woman, added to being an outsider, imposed on her an irresistible need to assert herself at every opportunity.’ Which is to miss the point, first, that in terms of the old paradigm of Tory leadership, being a woman was itself the extreme form of marginal, outsider status; and second, that it was natural that she should promote and seek the company of other marginalised men – cranks like Alfred Sherman and Paul Johnson, mystics like Laurens van der Post and the born-again Brian Griffiths, embittered outcasts like Enoch Powell and Ray Honeyford, men like Bernard Ingham and John Hoskyns whose previous Labour sympathies made them oddities in the Tory camp, émigrés from Britain like Alan Walters, Ian MacGregor and Robert Conquest. Her Jewish Cabinet members were by definition marginal men within the Tory Party – which had the useful extra twist that they would be properly grateful for their preferment and in all likelihood would never become rivals for the leadership. Can one imagine a Tory gentile being a successful Chancellor of the Exchequer for six years on end without ever being seriously discussed as a future leader? Yet such is Lawson’s position. It was natural, too, that within the Cabinet Mrs Thatcher should promote the likes of Norman Tebbit. Young writes of Tebbit’s scorn both for the Left, ‘for the well-heeled whigs personified by Roy Jenkins, whom he considered to have been the agents of national corruption’, and for ‘the Old Conservative establishment, epitomised by Macmillan and Heath, whom he considered to be responsible for keeping the likes of himself out of power. By a narrow margin, the latter group probably headed the catalogue of infamy.’ Such were the feelings that the Brownshirts harboured towards their Left, their over-comfortable centrists and the old Junker class who had kept them out of power.

Traditional Tories like Prior and Pym were slow to realise what was happening. Of Pym Young writes that ‘gentleman though he was’, he ‘wasn’t lacking in corridor savagery’ and illustrates the point by citing Pym’s remark: ‘The trouble is we’ve got a corporal at the top, not a cavalry officer.’ Assessments of Thatcher cited by Young reflect a belated patrician fury as the fact of their dispossession sank in, though Young himself sometimes fails to realise this. Thus he instances Lady Warnock feeling a ‘kind of rage’ as she sees Mrs Thatcher on television choosing her clothes at Marks and Spencer and reckons there was something ‘obscene’ about it ‘in a way that’s not exactly vulgar, just low’. Lady Warnock is here adduced by Young as representing a paradigm of the intellectuals’ rejection of Mrs Thatcher. This is to miss the point entirely. Lady Warnock is an old-style mandarin who at first gained considerable preferment under Thatcher – as late as 1985 she was campaigning energetically in favour of her Oxford honorary degree. At this point, for some reason, Lady Warnock lost favour and she now seems to be furious at being dropped by someone who shops in Marks and Spencer. Her response to Mrs Thatcher, bespeaking pure class disdain, typifies the wounded reaction of an older class of notables who find themselves downgraded under Thatcher’s New Order.

Thatcher was, in a way, right to accuse the Tory old guard of defeatism. They didn’t like national economic decline any more than the next man, but tended to assume that it was somehow a matter of the tides of history – something you banged on about but didn’t really expect to reverse. Similarly, you banged on about the outrageous presumption of the trade-union barons, but at bottom you felt that the trade unions were just a bloody nuisance you couldn’t do much about. This defeatism was easily perceptible to the trade unions, who accordingly expected things to go on much as before and were thus taken unawares by Thatcherism in much the same way as the Tory old guard were. During the 1978-1979 ‘winter of discontent’, Alan Fisher, the NUPE leader, challenged with the damage he was doing to Labour prospects, replied that it didn’t much matter because no government could be worse than the Callaghan one they’d got. A similar, wrong-headedly cavalier attitude was apparent across wide sections of the Labour movement, which accordingly felt free to indulge in fratricidal strife, just as the German Communists and Social Democrats had in the early Thirties. In looking back to the late Seventies under Callaghan we are looking back at our own Weimar, our own Hindenberg.

Among Mrs Thatcher’s coterie the trade-union issue was viewed with quite surpassing bitterness. As early as 1977 John Hoskyns and Norman Strauss, acting at Keith Joseph’s behest, produced a report for Mrs Thatcher entitled ‘Stepping Stones’, which asserted that ‘the one precondition for success will be a complete change in the role of the trades union movement’ – by which was clearly meant nothing less than the movement’s rapid and total emasculation. The danger, they warned, was that a Tory government would be tempted to ‘get on with’ the unions – which, they insisted, would mean selling the country down the river. ‘We may have to take greater political risks than we had anticipated,’ warned the report, whose apocalyptic and alarmist language meant that it stayed secret. Mrs Thatcher, Young tells us, was ‘tremendously excited by what she read’. Thereafter, the trade-union theme recurs insistently, and within the Thatcherite camp a person’s attitude on this issue was treated as the benchmark of true Conservative purpose. This brought enormous pressure to bear on the Tory spokesman on the unions, James Prior, who clung to obstinately moderate views. The tenor of that pressure is best judged by the way that Tebbit, to applause from Thatcher, ‘likened Prior’s softness on industrial relations and especially the closed shop to “the morality of Pétain and Laval” ’.

At this point Jonathan Miller’s phrase ‘commuter idiocy’ comes drifting back. Was there anyone in the Sixties and Seventies who did not at one time or another find himself standing miserably on a station platform waiting for a train which, due to industrial action, was late or might not arrive at all? Among one’s fellow passengers was always at least one furious business gent who wanted the railway sold off on the spot and the strikers dispatched, within the next ten minutes, to Botany Bay. Tebbit’s comparison of Prior giving in to the Unions with Pétain and Laval giving in to Hitler was just the sort of language those furious business gents would speak. The fact is that those who staged those guerrilla actions in the public sector – the protest stoppages, go-slows, work-to-rules and demarcation disputes as well as the straightforward strikes – seriously underestimated the extent to which they were playing with fire. That furious business gent on the platform was a thoroughly noxious chap, a bullying Home Counties, Telegraph-reading snob, but if you drove the other passengers mad for long enough they would, in their frustration, line up behind him. Which is pretty much what happened.

Surprisingly (to me), Hugo Young seems to take Thatcherism’s assessment of its economic record pretty much at face value. It is perfectly true that many British companies and institutions became leaner and meaner as a result of the 1980-1981 recession, but it is also true that many died and that many more live on in a state of fragile anaemia. At the same time, the wilful undermining of state schools and universities, together with the almost complete neglect of industrial training and retraining, is producing a work-force which is falling behind those of our competitors in education and skills. It’s true, the fall in world commodity prices brought inflation down and made industry more profitable, while the coming on stream of North Sea oil removed – for a while – the old balance-of payments constraint to growth: but this was luck – not policy.

At the moment, we are told, we have almost an embarras de richesse, with a budget surplus of £14 billion. And we have had a protracted boom. The Government boasts that it has launched one state industry after another into the private sector, that it has set enterprise free, that conditions for the private sector have never been so good. So why did the private sector run at a £15 billion trading loss last year? And why is it projected, even by the Treasury, to run another £15 billion trade deficit this year? It doesn’t sound as if the private sector is really so healthy. Relative to the size of the two economies, our trade deficit is already bigger than America’s, itself considered a major threat to world financial stability. And what in God’s name is our deficit likely to be as North Sea oil production winds down? To finance these huge deficits we have to borrow foreign money and to suck that in we have to offer very high rates of interest. These interest rates are damaging to investment and they keep the currency too high, hurting exports and favouring imports. So we attract loans to finance our trade deficit by means which only worsen the trade deficit. Is this successful management?

The pound is now 70 per cent higher against the dollar than it was in 1983 and considerably higher against other currencies too. Quite clearly this makes us uncompetitive: but we push interest rates right up to make sure we stay that way. Why do we keep the currency so ludicrously high? Well, you see, that forces the private sector to keep wage increases down to our competitors’ level, so that we don’t become uncompetitive. But it doesn’t: wages are at present increasing at an annual rate of 9 per cent (14 per cent for company directors), which is far above our competitors’ rates, and we are losing market share sharply. Is this successful management? But we do have a nice, fat budget surplus. Yes, but when we ran a budget deficit we borrowed by issuing Gilts – at relatively low interest rates because they were backed by the state itself. Now we have a trade deficit the same size as the budget surplus and this we finance by attracting hot money, not backed by the state and therefore at much higher rates. So all we’ve done is to substitute short-term borrowing at high rates for long-term borrowing at low rates – the classic recipe leading to the bankruptcy courts: except we are now told that this is an aspect of ‘the economic miracle’. As part of this ‘miracle’, we are told that we are now doing even better than West Germany. Strange that our trade deficit with the West Germans was £12.7 billion last year.

Meanwhile we are promised yet more cuts in income tax. But we know that such cuts are import-intensive in their effects in a way that extra public spending is not – and so can only add to the already mountainous trade deficit. Is that good management? Thanks to the oil boom of the past decade we have at least built up a huge portfolio of overseas investments which yield a major invisible inflow of dividend payments. But if we go on running up huge trade deficits we will end up making ever greater interest payments on the cumulative trade debt thus created. In the end, this will wipe out the net benefit of those foreign dividend payments: indeed, we could end up running down that stock of overseas assets to finance our domestic consumption. It seems clear that, one way or another, the approach of 1992 will see the crunch. A variety of scenarios exist, but they all lead to the same dénouement: a major sterling collapse and a consequent inflationary surge. Of course, when that happens that furious business gent on the station platform will have some fresh commuter idiocy to explain it. But fewer of the sensible passengers will be listening to him by then. And some may even be sidling away.

Send Letters To:

The Editor

London Review of Books,

28 Little Russell Street

London, WC1A 2HN

letters@lrb.co.uk

Please include name, address, and a telephone number.