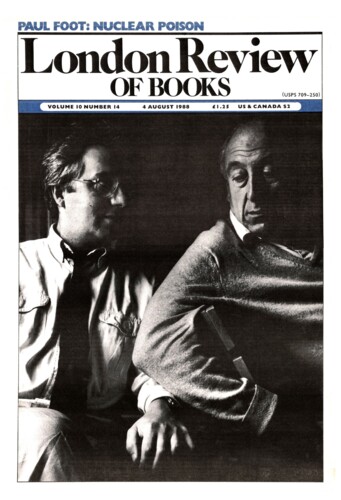

AH: I was thinking about the unusual shape of your career as an author – having written a collection of stories during the war when you were in your late teens and not published them for thirty years, then later publishing two books, one of which is almost entirely about the period of the war. The war seems to be a magnetic subject in what you’ve written. I wondered what sort of war you’d had.

FW: I had very much the same sort of war as is described in the books. I was in my teens. I was first at Oxford, then called up, invalided out of the Army, and did a TB cure. So the theme of those first stories in Out of the War, and to a certain extent of The Other Garden, is the war as seen by people who aren’t participating in it. The reason I wrote about it then was that it was what was going on at the time, and the reason, I think, why I write about the war now is because it isn’t what is going on at the time. I sent a few of those stories to publications but they were rejected, and the whole collection was turned down by a publisher. I thought, well, they aren’t any good, so I forgot about them, and wrote other things – reviews, interviews. Then when I came back again to try and write fiction in the late Seventies I didn’t feel that my responses to what was going on around me in the present were fine enough. It seemed to me much easier to write about the past, partly because so much of art is selection, and memory and forgetfulness have done the selection for you in a way – what I did remember, I remembered for a reason. Also, though I don’t think my stories are particularly libellous, I felt a sort of embarrassment at writing about people I know, which was solved simply because most of the people I wrote about in Mrs Henderson and The Other Garden are dead. It’s not so much that I’m obsessed by the war or by that period of my life. In a way, the theme of those books and of the early stories is a side of life which is boring and vacant, but which was rather dramatised by the fact that the war was going on. People like myself were immobilised in one way or another. So that’s a ready-made paradoxical situation. I think what I’ve always wanted to do in fiction is to write about that – the hours and hours and hours, the enormous proportion of life which is spent in a kind of limbo, even in people’s active years. It seems to me that isn’t sufficiently celebrated in fiction. The obvious reason why it isn’t is that it’s so terribly boring.

AH: But boredom can be made fascinating. There is a sort of unspoken intensity about these periods of suspended animation, and one does feel that they are somehow deeply typical of life. I can’t think of anybody else who has really done this, or has come near to doing it so well. In this state of mind your characters become preoccupied with trivial, ephemeral things which take on a comic resilience of their own. Were you very absorbed in popular music and cinema?

FW: Yes, very much in the cinema, but I think almost everybody was then. It was a fairly universal thing. It later was turned into a camp thing but it wasn’t necessarily that at the time. I can’t think what the equivalent now would be – television isn’t quite right for various reasons. It was a sort of lingua franca. Like people now talk about EastEnders – then it would have been films, but the movies were more dreamlike, more romantic. I remember when I was at Eton, I hated games and somehow managed to get out of them by saying I had sinus trouble. My housemaster said: ‘You must lake some exercise, why don’t you bicycle?’ So I bought a bicycle and would go into Maidenhead, take my school cap off, and go and sit in the cinema – when I should have been doing other things. Later on it stood me in very good stead, because when I went to the Sunday Times Magazine in the Sixties it was about the time of a certain camp interest in cinema, and I commissioned endless, endless articles about Hollywood things. I found that I’d actually become a kind of expert in Hollywood glamour-films. About the music, I was never a serious jazz buff or anything like that – it was just as with everybody in those days. You had a favourite film-star and a favourite tune – you had a tune on the brain. I was always mad about some singer or mad about some tune. I didn’t have very good taste particularly, but that wasn’t the point. It was an alternative. I mustn’t make myself out to be a total idiot because I wasn’t – I was quite intelligent. But along with this intelligence went this other goofy kind of thing.

AH: What was Eton like?

FW: I kind of ducked it. I sometimes really wonder if I was there. I sometimes feel I’m one of those people who pretends he went to Eton, because I can’t remember anything about it. But I think I did go there. I hated school really – though nothing awful happened to me there. I felt I was being forced to do something I didn’t want to do. It was such an effort just to turn up at the right place. And sometimes it’s got a funny joke name and you don’t know what it means: you’ve got to be at Toggers or something. I hated all that. But I had a very nice housemaster – George Lyttelton of the dreaded Letters – who allowed me to educate myself. He thought it was rather amusing that I was reading Proust, though he didn’t think it was a frightfully good idea. I was always, as a child, fascinated by things considered unsuitable for children. Of course, I didn’t really understand them but I was very excited and glamoured by it all. I suppose excitement and glamour come into reading a lot. I’m talking about what I was like so long ago, but I think there is a way in which one never changes. One changes tremendously in some ways, but there’s something about how one was then that remains. And maybe that’s why I’ve so far written about that period of my life.

AH: Re-reading the Out of the War stories, I’m amazed by their finesse. They breathe self-confidence. It seems to me extraordinary that after failing to place them you decided that you weren’t cut out for fiction. Where were you living at this time?

FW: I lived in a house in Trevor Square, just opposite Harrods. I moved there with my mother immediately after the war in 1946, and stayed there for absolutely ages.

AH: How literary was your family?

FW: Well, my mother was the daughter of Ada Leverson, who was a friend of Oscar Wilde: he called her the Sphinx. She was very literary. I don’t think my mother would have said she was literary herself, though she did later write books, which were published. My father was much older than my mother. She was a VAD in the First World War, and through that became a great friend of my half-sister – my father’s daughter – and then met my father; he was nearly sixty when I was born. He was a soldier, but he loved writing, he loved the Russians.

AH: Did you know your grandmother?

FW: Yes. I was nine when she died. I absolutely adored her.

AH: Did she tell you any stories about the Wilde era?

FW: No, she never talked about it; I was only a child, so she probably wouldn’t have. She lived very much in the present. Some younger people saw her as a sort of relic – people like the Sitwells and Ronald Firbank and Harold Acton – but all that rather bored her. She was very up to the minute, and would be full of the latest musical comedy or the latest thing that had been written. But she wrote a memoir of Wilde, which I published along with his letters to her in a magazine I set up called the New Savoy. I did it with somebody called Mara Meulen. It was rather good. There was only one issue: it was rather squat – a small, thick, yellow thing, with a ghastly woodcut on it. Nobody knew how this woodcut got on it. There was a piece by Anthony Powell called ‘A Reference for Mellors’, which was about somebody coming to Lady Chatterley for a reference for a gamekeeper. The magazine sort of launched me on a career, because Alan Pryce-Jones, who was then the editor of the TLS, gave me a lot of reviewing work.

AH: How did you see your future then?

FW: I suppose I feebly wanted to be a writer, but, apart from those stories, I couldn’t think what on earth I was going to do. I got my first job as a guide at an exhibition called ‘Britain can make it’ at the V & A, which was rather touching. It came on just after the war – absolutely hideous textiles and things. There was one very famous thing that everyone wanted to see: I can’t remember what it was now – it might have been a tractor, or a bed. I stood in the sport and leisure department with a lot of out-of-work actors and told people where the lavatory was, and where this thing was. Then I did some work for the New Statesman, and then I did quite a lot for Alan Pryce-Jones, and Anthony Powell, who was the fiction editor of the TLS. He was very nice, he recommended me to the Observer. The literary editor of the Observer then was somebody called Jim Rose. He wasn’t the most literary person in the world. He was so funny. He was always quoting his mother. I lived in dread of Mr Rose’s mother, because he would always say: ‘My mother wouldn’t understand what you mean by this,’ ‘I don’t know if my mother could be expected to follow this.’ When he got the job of literary editor he gave himself the task of reading an essay by Max Beerbohm before breakfast every day.

AH: But you were still writing for the TLS all this time?

FW: Yes, though I stopped with a thud when Alan Pryce-Jones left and Arthur Crook came. I think I was too associated in his mind with the frivolity of the Pryce-Jones era.

AH: Wasn’t the TLS lively and good under Pryce-Jones?

FW: I thought it was, I loved it. It was very unLeavisite, or anything like that. I think it made Leavis more angry than anything else, even the Sitwells. He saw it as being the worst example of a metropolitan, frivolous, unearnest thing.

AH: Did you mind writing anonymously? It’s a peculiarity of those TLS ‘middles’ that they were perhaps the most prestigious literary essays being published at the time and yet they were anonymous.

FW: No. I’m not for anonymity, but I didn’t mind myself. Having given up the stories, I slid happily into this other thing of being a literary journalist. Then in 1953 I made a resolution that I must get a job that year. So I did get a job, with a very funny publisher called Derek Verschoyle. He was the literary editor of the Spectator. He had lots of wives and was very like a publisher in a Muriel Spark novel. I rather wonder if her latest isn’t about Derek Verschoyle. He was really rather a crook, though very smooth, and it now turns out that he had done some dirty tricks for MI6. He would arrive with terrible black eyes, given him by his wife. His girlfriend also worked in the office, and I shared a room there with a very fascinating person called Mamaine Koestler, Koestler’s wife (not the one he killed himself with), a very beautiful girl and rather famous at the time. My half-brother had been in love with her; she left him for Koestler, which my half-brother never got over. We used to read books together in the mornings. But then Mamaine died – of asthma, and of being depressed by Arthur Koestler – which was very upsetting. I’m not being very coherent about all this, but it was all part of the atmosphere.

AH: Where was the office?

FW: Just off St James’s, Park Place or something. Very pretty, a very old rickety building, with one lavatory, and a funny person who lived at the top. And then all the writs began arriving. Verschoyle wasn’t a shy man, but he couldn’t tell anybody. In some mysterious way he did go bankrupt, and what was left of him was taken by André Deutsch, including me. So in 1955 I was working for André Deutsch. I was there for four years, and I sat in a cupboard and read books for them. I was paid very, very little – even for those days. The idea of reading for a publishers is always meant to be a wonderful thing, where a wonderful manuscript arrives and you read it – and most people who’ve been publishers’ readers will tell you that that never happens. But one day Diana Athill came into my cupboard and said: ‘Will you just have a look at these, they’re by a West Indian writer, V.S. Naipaul’, I read them and wrote Diana a report in which I said: ‘I know we never do short stories, but we must do these, they are incredibly good.’ Then he turned up at the office with the beginning of his first novel, so, typically, they didn’t print his short stories, they printed his first novel, and then his second novel. Eventually they did print his short stories. He was living in North London. He was married, probably being kept by his wife, who was a teacher. I edited his books and we became great friends. The other thing that bore fruit during my time at Deutsch was the Jean Rhys saga. I’d always thought her books were wonderful. I showed them to Diana, who agreed, but said we couldn’t republish them, and then we discovered that she was still alive. I read her immediately after the war, and I remember Anthony Powell said: ‘Oh you must meet Julian Maclaren-Ross, because he knows all about Jean Rhys.’ He asked me for a drink to meet him, and Maclaren-Ross said she’d died the other day in a sanatorium. So I really did think she was dead, and in my articles would often mention her as ‘the late Jean Rhys’. Then Diana saw an article in the Radio Times saying that she’d been discovered, because they did an adaptation of Good morning, midnight. So I wrote to her and she wrote back. Then I left Deutsch to join Queen Magazine. They wanted me because of Mark Boxer, the Art Director, who had become a great friend. There was a sort of troika: Jocelyn Stevens, who’d bought it, Mark Boxer and Beatrix Miller, who was brought in as the editor, and who later edited Vogue. She was the one who had any sense, and Mark had all the impatient brilliant ideas. Mark asked would I be their theatre critic. I was always put behind a pillar on the second night. I don’t think I ever went to a first night, because Queen Magazine was then considered very tatty. It was a dream of mine to be a theatre critic, but it turned out to be rather a nightmare, because that was a period when there was a tremendous fashion for booing – there were a lot of articles written about it. There was an awful woman called Gallery Nell, who would go to a first night and if it wasn’t by Noel Coward she’d start the most terrifying booing going.

AH: Was she thrown out?

FW: No, no. The play would stagger on for another night, when I would be there reviewing it. Gallery Nell would still be there booing it, and then it would come off, and as I was writing for a fortnightly, I never got to write about most of the things I saw. It was rather like going to a bullfight – I can’t tell you how awful it was. This period has now gone down in history as the great renaissance, with John Osborne, the Royal Court, but most of the time, night after night, you would go and see wretched actors, and there would always be something in the play like ‘God, is this never going to end?’ and Gallery Nell would seize her chance. One of the most booed plays I saw was a musical called Keep your hair on! in which Jocelyn Stevens, my boss, had invested some money. The sets were by Tony Armstrong-Jones, who was also on the magazine and became a great friend of mine. And I was vaguely given to understand that a good review would be welcome: but I needn’t have worried, because Gallery Nell booed it off the stage. Then I became literary editor of Queen Magazine. In a way it was rather awful, but I enjoyed it. I thought I was too grand to do interviews, but then I was asked to interview Elizabeth Taylor and Richard Burton on the set of some film. So I said, what the hell, I’ll do it. That initited the interviewing period of my life: I remember coming back and thinking. ‘It’s an absolute doddle, interviewing’ – I mean. Elizabeth Taylor was more famous than the Queen at the time, and if she just came into the room and said ‘Oh Christ!’ it was fascinating, you’d hooked your readers. I got to absolutely love interviewing people. In 1964 I left Queen and followed Mark Boxer to the Sunday Times Magazine: it was a couple of years after it had started. Nobody knew what to call me, so I thought I’d be called show-business editor – I wanted to do popular things. I was looked upon with grave suspicion by the literary editor, Jack Lambert, who thought I was after his job and was very paranoid about me always. I thought: ‘I’m not going to be too literary with this, I’m just going to have some fun.’ In a way I think I took it too far, and would rather block serious ideas. People would say, ‘I think it’s time we had a profile of John Fowles,’ and I would say: ‘Christ! No! Forget it!’ Some people didn’t like me and thought I was a bad influence. I suppose I was élitist, something that I’ve always thought I wasn’t. I rather disliked the sort of person I became at the Sunday Times.

AH: Were you very ruthless?

FW: No: I never was powerful enough, I avoided power. Then Mark stopped being the editor and there was Godfrey Smith, and then Magnus Linklater, both of whom were very nice. I was then called senior editor. The other day I went to see James Fox, who had the French edition of White Mischief, which I come into. He’d put originally that Francis Wyndham, one of the senior editors, wanted Cyril Connolly to write something, and I immediately looked myself up and it said: ‘Francis Wyndham, un des rédacteurs les plus âgés’, as if I was one of the oldest editors there’s ever been.

AH: Was there a feeling of tension and difficulty on the magazine?

FW: Well the paper was very jealous of the magazine. Harry Evans didn’t like me. As well as all the articles about Joan Crawford and so on, I wanted to get very journalistic things and political things into the magazine, which infuriated the paper.

AH: I remember it did a lot of stories about wars abroad, Vietnam, Biafra, Bangladesh. There was a time when it was traumatic reading; it was full of horror.

FW: Yes, and there was Don McCullin, of course. I didn’t actually travel with him, but I edited his stuff when it arrived back. The paper hated all that, but we were in picture journalism and it was something we obviously had to do, and he was a wonderful photographer. It all went on until 1980 – much too long. I was actually fired, but I was longing to leave. The paper didn’t come out for a year during the closedown. Everyone else went on, as if it was the Blitz or something, producing endless issues of the Colour Magazine which never came out. I couldn’t face it. I did turn up when it started again, but I’d got into the habit of not going to the office, and after a time I just couldn’t get there. By then it was a place to get out of, if you possibly could. The difficulty was to be fired.

AH: Go back to when Bruce Chatwin came on the scene.

FW: I slightly knew Bruce before, and knew he was absolutely a genius about art.

AH: In an intuitive rather than an academic fashion?

FW: I’m not sure. I knew that when he was 18 he was head of antiquities at Sotheby’s and head of modern painting. When Magnus Linklater took over as editor, David Sylvester, my neighbour and great friend, who had been art adviser, offered his resignation. So suddenly there wasn’t an art adviser. Bruce was at a terribly low ebb. He’d been working for ages on the book which eventually came out as The Songlines. He had an enormous manuscript of this book about nomadism, and couldn’t make any sense of it. He was absolutely bankrupt and miserable. Then the telephone rang and it was me and I said, ‘Would you like to be art adviser?’ and he said: ‘Yes.’ Then he came to the office and I took him and Magnus to the pub opposite. Bruce was absolutely brilliant. He couldn’t open his mouth without brilliant ideas coming tumbling out. But I could see that Magnus was a bit taken aback – he was so unlike a Fleet Street journalist. The first thing he had to do was one of those awful Sunday Times things, ‘The Thousand Greatest Pictures in the World’, which everybody hates, but anyhow he swallowed it and did it extremely well. One of his suggestions was that we should do something on Mme Vionnet – a brilliant suggestion, but he didn’t know who should write it. I said: ‘You, of course.’ He’d never thought of himself as writing such a thing. Then he started doing frightfully good pieces. He went to Russia and did an extraordinary thing on the Costakis collection of Constructivist art, and he did an interview with André Malraux. He says that I helped him, but I did nothing at all – he wrote extremely well. But there’s got to be somebody there for whom you write things, and I suppose he did them sort of for me. I went to New York with my friend David King, who was also on the magazine, to do some picture research, and Bruce did a very typical thing and followed on the next plane. We were having a drink at the Chelsea Hotel when Bruce turned up in his shorts with a rucksack and said: ‘I’m just off to Patagonia.’ And then he walked off. David and I finished our drinks, and got in a cab, and miles further on, on Broadway or somewhere, there was this figure striding ahead. And the rest is history.

AH: Do you still give him advice?

FW: Well, he always shows me his things. I only make very tiny suggestions – hardly anything on Utz, his latest novel. When he wrote On the Black Hill, which is dedicated to me and Diana Melly, he was living in Diana’s house in Wales; I was there a lot of the time, editing the Jean Rhys letters with Diana. We’d hear Bruce singing upstairs – he was really saying it, he had to hear it, and it sounded like singing. He would come down and read it to Diana, and give it to me to read, as I can’t take in things through the ear. That was the one on which I made most comments, because I just happened to be there. In general, I’m very anti-interventionist. When I worked for publishers there was an idea that I didn’t do enough. They would always say: ‘Dear boy, what we really want is an English Max Perkins.’ They wanted one to go off with the author to some awful cottage in the country, light a pipe, go through the thing, go for long walks on the cliffs, drink a lot of whisky ... I often thought that the thing that might have been edited out was the thing that, though not necessarily brilliant, made the book itself.

AH: Was James Fox another protégé of yours?

FW: Well, I don’t feel he’s a protégé. I mean, he’s a great friend. He came to work at the Sunday Times when he was very young; he was only 22. James did some frightfully good pieces. He would do much more controversial things than Bruce, about scandals or murders. But they would always stand up. He does endless preparation. Very unlike myself, because I was a very superficial journalist. One skates.

AH: You have the reputation now of being a kind of guru to many writers.

FW: I don’t want to overdo this guru thing. It isn’t really like that, is it? You just have friends and you do your job. Part of the fun of being on the Sunday Times was getting people to write for it who perhaps hadn’t thought of themselves as journalists. I was terribly nervous of ringing people up when I first got there – I thought it was terribly intrusive – but of course people are absolutely delighted: ‘Lord Snowdon’s going to do the pictures. Do you mind going to Poland for ten days?’ The sort of thing I would rather die than do, but everybody said yes. I remember ringing up Muriel Spark and asking her if she’d interview the Pope. And she did say no, but she didn’t say: ‘Shut up, you silly fool!’

AH: Perhaps we ought to go on to 1980. All sorts of things happened then.

FW: Yes, my mother died at the beginning of 1979. And this sounds ridiculous, but I gave up smoking, which had a terrible physical effect on me: if you’ve been smoking sixty a day since you were 14 you feel absolutely frightful when you stop. It must be like giving up heroin, the withdrawal symptoms, and I got a lot wrong with me. I got overweight. My whole body changed. How I felt then goes into the story ‘The Ground Hostess’, which I started in 1979 after my mother died. It took me rather a long time to finish. I’m not a very fast worker. I wrote the four shorter stories in Mrs Henderson over a period of about six years. It was only when I was half-way through the long one, ‘Ursula’, that I suddenly saw that the whole lot hung together as a book.

AH: One of the things I like about Mrs Henderson is the way that – allowing for changes and artistic licence – it does cover the span of your life. It’s striking, too, that, having said that, one actually learns remarkably little directly about you from it.

FW: Yes, a lot of people, including reviewers of The Other Garden, have been a bit fussed that I haven’t in some sense come clean.

AH: I think that’s the most fascinating thing about the books.

FW: I don’t do it to be coy.

AH: Do you have some sort of feeling that you don’t want to write about yourself?

FW: Well, I sort of feel that I am doing it. I feel my fiction is very revelatory.

AH: It seems to me that one of the most intriguing things about The Other Garden is that the narrator and Kay, the principal character, don’t have the kind of sexual relationship you think they might be going to have. You don’t explain the narrator’s feelings for the girl.

FW: I felt it was absolutely right not to say anything. I think it is perhaps a flaw if several people say they feel the need for more explication, but I don’t think it’s false. To be honest, that story was fairly autobiographical. I’ve slightly altered and slightly simplified Kay, but I think I have absolutely got what our relationship was like. One of the things I like about first-person narration is that it is like life, because in real life you know so little about other people. Maybe it’s just me, maybe everybody else knows everything about everybody. But I think one knows very little about other people. The girl who was the original of Kay was a very great friend of mine, but she never told me about her previous lovers. That’s why I leave them out. I think that’s why everything I write is so short.

AH: We haven’t really said how funny your books are. I know you’re not a Firbank admirer particularly, but I think you both have an ear for the absurd things people say. You isolate their gossip, and it takes on a crazy hilarity of its own. Do you fall about laughing when you’re writing?

FW: I don’t know that I fall about laughing, but I want it to be funny. One thing I consciously try is for things not to be all on one note. I don’t mean laughing through tears. But somehow to get that thing about life, where you can see the world as very funny one minute and then suddenly – probably for some physical reason, you just feel hung over – you see it all as not ...

AH: And what is your life like now?

FW: It’s very hard to describe my life. I don’t cook. I don’t drive. I don’t seem to be reading or writing at the moment. I never listen to music on my own, because it depresses me. But I suppose things do happen.

AH: You find it pleasurable, this vacancy nowadays?

FW: Well, I must say, every morning I wake up and think: ‘How wonderful, I don’t have to go to the Sunday Times.’ I remember when I first got out of the Army, and came to live in London. Trevor Square was very near Knights-bridge Barracks, and I used to hear reveille early in the morning at half-past six and think: ‘I don’t have to get up.’

Send Letters To:

The Editor

London Review of Books,

28 Little Russell Street

London, WC1A 2HN

letters@lrb.co.uk

Please include name, address, and a telephone number.