The seemingly intractable problem of violence in Northern Ireland has spawned a remarkable number of books, ranging from the voyeuristic and ephemeral to the illuminating and scholarly. There have been comparatively few attempts, however, to see the conflict from the perspectives of the individuals most directly involved. Now Max Arthur’s fascinating collage of soldiers’ reminiscences gives a voice to a group who are not generally believed to have (or to be entitled to) one, while John Conroy’s account is that of a sympathetic outsider nervously learning the codes and concerns of a small Catholic community at the eye of the storm. At the academic level, the heightened interest in Irish history in England has found a focus in the dynamic journal Past and Present, which has published some of the key articles by the younger generation of Irish historians. The republication of these, together with new articles on related topics, in Nationalism and Popular Protest in Ireland makes important work available to a wider audience, and offers an opportunity to assess some interesting trends in Irish historiography. At the same time more traditional concerns persist, and no other form of academic history achieves as wide a readership as biography. Oliver MacDonagh and Owen Dudley Edwards offer new interpretations of two men, each of whom dominated the politics of his time, Daniel O’Connell and Eamon de Valera. Their relevance to the current crisis is most apparent in the way each had to come to terms with the problems which sectarian polarisation, on the one hand, and militant extremism, on the other, pose for Irish nationalist politics.

Oliver MacDonagh is unique among Irish historians, not only for the range of his interests (the history of administrative, industrial and scientific developments, as well as demography and political and literary studies), but also in the care, polish and adaptability of his literary style. For his last book on Ireland, the award-winning States of Mind, he adopted the classic essayist mode; his splendid occasional pieces on Jane Austen’s novels have some of the dry, delicate precision of their subject. It is part of his strength that this remarkable range is focused chronologically on the first half of the 19th century, so that his knowledge of its literature, for example, informs his appreciation of its politics and has partly inspired his work on its administrative systems. He is equally at home with British and with Irish history, as befits the biographer of a man who made a major career in both countries and combined elements of both political cultures. His qualities come together triumphantly in this first volume of two, which brings O’Connell’s career to the victory of Catholic Emancipation in 1829. For it, MacDonagh has developed a narrative style designed to involve the general reader as well as the specialist. It is spare, lucid and forceful for the most part, while managing to create a surprising amount of room for evocation of places and people, as well as for passages of shrewd political analysis. It wears its great scholarship lightly, and makes even the most familiar aspects of the story full of fresh interest and excitement. A re-evaluation rather than a monumental ‘life and times’, its main debts are to Maurice O’Connell’s splendid eight-volume edition of his ancestor’ss correspondence, and, especially, to the letters between O’Connell and his wife, which are at the heart of a brilliant blending of the private and public lives. The book makes its most original contributions in areas where MacDonagh’s empathy with his subject is balanced by what is often an astringent critique – O’Connell’s work as a barrister and the imprint of this on his politics is a case in point, as are his Catholicism, personal and political, and his relationship (not least in financial terms) with his family.

MacDonagh’s title, The Hereditary Bondsman, comes from O’Connell’s regular rhetorical use of a couplet of Byron’s to define his own position and that of his fellow Catholics. MacDonagh’s O’Connell is a man driven by a ‘consciousness of degradation’ caused by discriminatory laws, including those against Catholic barristers taking silk. This prevented the chronically debt-ridden lawyer-politician from achieving his potential income. Indeed, ‘O’Connell may well have had more at stake in the Catholic question, materially speaking, than any other person in the United Kingdom.’ His resentment was both intensified and balanced by a remarkable self-confidence, and MacDonagh is particularly good at showing how the various elements in this complex psychology were rooted in his Kerry background and shaped by his education in France, London and Dublin. All of this made him at the same time a social conservative, opposed to revolution, and a philosophical radical, fearful of ‘the unleashing of the irrational in politics’. His own description of Catholic Emancipation as ‘one of the greatest triumphs recorded in history’ was on the basis of its being ‘a bloodless revolution’ involving ‘political’ rather than ‘social’ change. In MacDonagh’s view, its main radicalising influence lay in its confirmation of the end of Protestant superiority and Catholic deference, for long the aim also of the ‘Billingsgate’ and violence of much O’Connellite rhetoric.

Above all else, O’Connell, as MacDonagh portrays him, was a remarkable political pragmatist. The ‘basic pattern’ of his career was an endless ‘tactical oscillation’ between the two poles of collaboration with English Whigs and Radicals and attempts to make common cause with Irish Protestants; between political intrigue in England and populist campaigns in Ireland. He survived years of futility and defeat by an ‘elasticity’ which made him ‘perpetually resilient, flexible, fertile in device and ready for accommodation within the grand circle of the negotiable’. The key to his politics lay in his mastery of legal skills. He demonstrated ‘the lawyer’s ineluctable concern with the correctness of form and formulae, with legal effect rather than with moral stances or satisfactions – the advocate’s extravagance in framing claims, combined with moderation in settling for returns’. The second volume of the biography will be awaited eagerly, not least for its account of O’Connell’s career as a Radical at Westminster and his confrontation with a more militant nationalism in Ireland.

A similar confrontation marked the career of Eamon de Valera, and is a major theme of Owen Dudley Edwards’s biography. This is one of a series of ‘personal portraits’ of ‘the decisive figures in the making of British politics’ from the University of Wales, under the general editorship of Kenneth O. Morgan. ‘Personal’ it certainly is, but it is also the work of a distinguished biographer whose earlier subjects include Arthur Conan Doyle and P.G. Wodehouse. This may appear to be a strangely assorted group, but Edwards has always been fascinated by enigma and mystery, and the psychology of people who are particularly successful manipulators of language The author of the Irish Constitution, and of the romance of an idealised peasant Ireland, can be seen to have more than a little in common with the creators of Sherlock Holmes and Blandings Castle. Like MacDonagh’s, this biography is also a work of reassessment rather than of revelation, and is marked by an interesting rapport between author and subject. Edwards’s fear of offending, expressed in the Preface, should prove groundless. His claim to write as ‘one of the plain people of Ireland’ may be disingenuous, but his description of himself, in relation to ‘Dev’, as ‘one of his own’ rings true. While he breaks new ground in discussing de Valera’s family background, he does so with great sympathy and sensitivity, and much of the book offers a trenchant defence of its hero’s conduct in such controversial areas as the Civil War and the 1937 Constitution.

De Valera was not illegitimate, in Edwards’s opinion, but ‘his social circumstances’ – especially the failure of his mother to bring him back to America after her second marriage, despite his pleas to her as a 14-year old boy – ‘left a strong presumption of illegitimacy’. Edwards lays great stress on the consequences of this rejection, speculating, for example, that later successful attempts to establish a relationship with his mother were a major factor in his otherwise inexplicably long sojourns in America at critical periods for Ireland Even more speculative is the argument that the bizarre attack in the 1937 Constitution on the idea of women working outside the home owed a lot to the fact that his mother’s need to work was given as the reason for her inability to keep him. Edwards’s professional expertise in American history means that Dev’s Americanism is given a new prominence in this study – not only his rapport with Irish-America, but the influence of President Wilson on his policies and tactics. The belief that Dev’s responsibility for and role in the Civil War were minor is more controversial; and even more so is the claim that the sectarianism of the Constitution was justified because it involved a tacit abandonment of the claim to the Six Counties, and was ‘the means of containing Catholic rhetoric while keeping a tradition of representative democracy’. This involves the author in an argument of de Valera-like sophistry and complexity.

This biography offers many new insights into a politician whose stock-in-trade was mystification. Many of them, however, are in characteristic digressions which, while they may amuse and instruct the informed Irish reader, may cause problems for the English audience at which the series is aimed. The treatment of de Valera’s life after 1922 is very sketchy, and major areas like the ‘economic war’ with Britain hardly get a mention. What Edwards offers instead is a sympathetic sense of the man, and an analysis of his political style, that of the Biblical ‘king-priest’ of a secular church. It was, however, even more marked by a pragmatism akin to O’Connell’s, and a repudiation on de Valera’s part of his militant Republican past, except (ambiguously and dangerously) as one ingredient in a finely-calculated rhetoric.

The relationship between constitutional politics and violence for much of the 19th century had to do with agrarian movements rather than extreme nationalism; and a major part of O’Connell’s achievement was to divert popular agitation into safer political channels. One of his comments on the victory of 1829 was that ‘the people will be taken out of our hands by Emancipation, as we took them from Captain Rock by our agitation.’ The widespread ‘Rockite’ revolt of the early 1820s is not dealt with in Nationalism and Popular Protest in Ireland, but ‘Houghers’, ‘Defenders’, ‘Ribbonmen’ and Land Leaguers are. The title of this excellent volume is rather misleading. Not all the articles deal with ‘popular protest’ and those which do demonstrate for the most part their lack of a ‘nationalist’ dimension. It is unfortunate also that only the volume numbers are given and not the dates of the original appearance of the articles in Past and Present, all the more so as they are grouped here by theme and out of sequence. It seems odd, too, that two ‘introductions’ were thought necessary. The first (the only one so designated), by Roy Foster, is an informed and thoughtful piece which situates the articles in the context of the modern Irish historiographical revolution and provides an excellent guide to further reading. By contrast, V.G. Kiernan’s ill-informed and oddly traditionalist meander through Irish history in search of ‘the emergence of a nation’ manages either to ignore or to misunderstand that revolution completely.

Two minor themes of the volume figure in articles on the religious roots of Irish political ideologies (by Nicholas Canny and David Miller) and, rather incongruously, on the role of the potato in Irish demography (by K.H. Connell and L.M. Cullen). All four are seminal pieces, which have stimulated lively debates and further research. What gives most coherence to this collection, however, is a series of eight articles on popular violence, from the shadowy ‘Houghers’ of the early 18th century to the Land War of 1879-82. Most deal with agrarian movements which display common characteristics of localism and conservatism, and centre on issues arising from changes in land use or occupation. Sean Connolly’s hitherto unpublished account of the ‘Houghers’ outbreak in Connaught in 1711-12 brilliantly overcomes the problems of scanty source-material to provide a vivid anatomy of ‘Hougher’ grievances and membership, including the surprising involvement of some gentry. This was also a feature of the ‘Rightboy’ movement in Cork in the early 1780s, featured in Maurice Bric’s fine account. Here the involvement of the gentry group is linked to county politics as well as to the trans-class grievance of Tithes, and may account for the ‘Rightboys’ sophisticated organisation. All the work on agrarian secret societies (notably by Jim Donnelly) bears out Tom Bartlett’s claim that the violence they produced in this period was quite limited by European standards, amounting to only 50 deaths in the 30 years prior to 1793. In sharp contrast, 230 lives were lost in little more than eight weeks in the country-wide resistance against recruitment into the Militia in that year. This is analysed in Bartlett’s major article, which links the dramatic escalation of violence to the destabilising effects of the Relief Act that gave Catholics the vote in the same year, and argues that it constituted a massive breakdown of the traditional ‘moral economy’ (or patterns of paternalism and deference) which was to culminate in the even more violent horrors of 1798.

After the Union, the pattern of localised agrarian violence resumed, but with added sectarian elements, which were also a legacy of the 1790s. The longest-lived and most extensive movement of this period was ‘Ribbonism’, the subject of two important studies in the Past and Present volume. Tom Garvin argues persuasively that it was a link between late 18th-century Defenderism and the later Fenian and Hibernian movements, but neither he nor Michael Beames can overcome the problem of the lack of any convincing or corroborated evidence, either for Ribbonism’s claimed regional or national organisation, or for the attribution to it of a ‘lower-class nationalism’. Beames is good, however, on the urban dimensions of the movement, and its operation as a mutual aid or friendly society, as well as a terrorist organisation. A second article by Beames focuses on peasant assassinations in Tipperary in the decade before the Famine. These reflect none of the politicisation attributed to Ribbonism, being instead in the older Whiteboy tradition. Most of the victims were landlords or their agents, and ‘it is the occupation-of-land issue which is predominant.’ Landlords fare rather better in Theo Hoppen’s sparkling analysis of their role in mid-century politics, which also stresses the local rather than the national, and ‘mechanics and manipulation’ over ideological factors.

The theme of agrarian protest is continued in two new contributions to the lively debate on the Land League. Donald Jorden joins in a key issue of that debate – the nature and limitations of the class alliance involved in what is another local study (despite its title), of Mayo. His economic/demographic analysis of the county in core-periphery terms is impressive, as is his outline of the new political power of shopkeepers and tenant farmers in the 1860s. However, his argument about the class basis of the Land League lacks solid support in the surviving evidence, and is sketchy and impressionistic. Such a change can hardly be levelled at L.P. Curtis Jr’s leisurely and heavily-detailed study of a hitherto unregarded aspect of Land League activity-the campaign against hunting, widespread in the winter of 1881-2. Excellent on the social and economic dimensions of hunting, and on the psychological impact of the campaign for both landlords and tenants, it is more descriptive than analytical, and is marred by odd lapses into hyperbole, as, for instance, when he speaks of the campaign reflecting ‘aspirations for an end to British rule’. The nature of nationalist opinion is assessed far more realistically and astringently in the final article of this volume, David Fitzpatrick’s brilliant ‘Geography of lrish Nationalism, 1910-21.’ Its opening pages are a marvellous antidote to the insidious inflated rhetoric of nationalist interpretation. For example: ‘Whenever the gospel of nationalism is preached, some grow excited, some yawn or look at their watches, some remain preoccupied with farm or family, some snigger or scoff some hurry to the police barracks.’ Testing the value of different sources lot mapping the distribution of nationalist activity during the revolutionary period, he argues that it was ‘above all a rural preoccupation’ Participation in nationalist organisations was ‘in part a barricade against boredom, in part a channel for local needs’, and was made easier in the countryside by the greater immunity from detection and punishment by the forces of law and order. Fitzpatrick’s complex statistical argument hasn’t pleased everybody, but it is kept out of the main body of the text, which will be read for its general insights and iconoclastic tone long after the statistical debate is forgotten.

The current phase of ‘nationalism and popular protest’ in Northern Ireland follows a similar pattern of confused motives, expressing communal fears and aspirations, as well as alienation from the state apparatus, and the exploitation of this in various ways by the hard core of the ideologically-committed and the psychologically-disturbed. Unfortunately, neither of the two new books which offer contrasting first-hand accounts of the ‘troubles’, shows much awareness of their historical dimensions. The soldiers interviewed by Max Arthur obviously shared the view of the Commando Corporal who thought the history briefings they got before their tour of duty an irrelevance; less excusably, the American journalist John Conroy’s ‘Belfast Diary’, while regularly invoking the historical record, can manage little more than an ill-informed version of the Republican nationalist account. Arthur offers a tapestry of voices’, by organising excerpts from interviews with unidentified soldiers from all ranks and regiments in chapters which mainly follow events since 1969, but with special chapters on Belfast, South Armagh, bomb-disposal and (most interesting of all) the UDR.

Charles Townshend, in his important analysis, Political Violence in Ireland: Government and Resistance since 1848, stressed the problems for the British state in attempting to counteract terrorism, in Ireland as a whole before 1921, and in Northern Ireland since then. These included the rigidities of hidebound legalistic concepts, as well as the inappropriateness of the Army as a law-enforcement agency, especially in situations where the legitimacy of the state is at issue. The testimony of Arthur’s soldiers, and of the Clonard Catholics among whom Conroy lived, underlines the continued force of this argument. A recurring theme in Arthur’s compilation is the difficulty felt by soldiers in coping with the hostility of civilians (and especially of children) and there are many examples of their personal hurt and bewilderment, as well as of professional frustration. ‘My saddest moment in Northern Ireland wasn’t being shot at, or bombed or attacked by rioting crowds, but the first time I was spat at.’ Arthur’s aim of ‘a neutral non political approach’ is maintained in the grim chronology of events he begins with (a reminder, too, of how much and how quickly we forget even the most horrific atrocities), but inescapably, much of the testimony he records is dominated by justification of the Army’s role, and refleets the preoccupation with public relations which such a role has increasingly involved. The Army’s professionalism and detachment are endlessly stressed, often in terms of soldiers being ‘normal everyday blokes, professional blokes, doing a job like what a priest does’

What makes this book such compulsive reading, however, is the accumulation of incidental detail: a reflection both of the training in observation skills and of the tradition of raconteurship which are so much part of Army life. Largely missing are the more negative and unattractive aspects of military culture, and little thought is given to the Army’s contribution to the escalation as well as the containment of violence. Doubt and disenchantment are expressed, but so is enthusiasm for service in Northern Ireland – ‘professionally a rewarding job ... When you’re trained to do a job you want to do it’ Despite its limitations, this is an important documentary record, not least in the articulation by the ordinary soldier both of official rhetoric and of the unspoken assumptions behind it. There is also an interesting contrast between the attitudes of those with Irish (including Republic of Ireland) backgrounds and those from mainland Britain, For many of the latter, the province is a ‘foreign country’ and all ‘the Irish’ an exotic but irrational and uncivilised people – a colonial stereotype as old as the Anglo-Irish relationship.

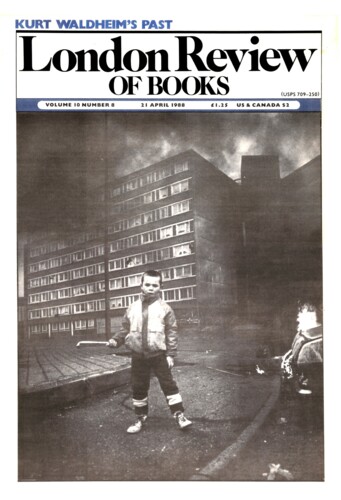

The stereotypes which populate John Conroy’s War as a Way of Life also owe much to the propaganda war – but this time the source is Provisional Sinn Fein, down to the tone of bland neutrality. Clearly concerned to combat ‘the barbarian view’ of the IRA which ‘prevails in the United States’. Conroy presents his ‘diary’ of his experiences of Catholic Clonard in Belfast (mainly during 1980) as ‘a street-level view of the war from the streets most affected’. In fact, this is not a diary, but an illustrated analysis/polemic, with as much editorialising as reportage: and the streets are almost invariably Catholic. Conroy writes well, and is at his best the linked series of ‘colour’ pieces at the core of the book. These deal mainly with the ghettoisation of this Catholic working-class area, and the way its people relate to the outside world – to the welfare state, local government, the Church and the educational system, as well as to Protestants and the Police and Army. Internally, the ghettos main power relationship is with the Provisional IRA, here presented in a chilling but largely favourable light, and under the guise of an objectivity which is fundamentally dishonest. The IRA of these pages attack only the security forces (civilian casualties are excused as being due to ‘horrendous mistakes’) and the petty criminals who batten on the ghetto poor. The punishment of the latter by kneecapping (here, quite a civilised business) is a form of ‘rough justice’ largely ‘acceptable’ to ghetto residents. By contrast, the atrocities committed by Protestant paramilitaries or the security forces are described in gruesome detail.

In an epilogue bringing the story up to 1985, Conroy claims that the new political role of the Provisionals had had ‘stunning results’ and he compares their position after the Assembly elections and hunger strikes to that of the ‘old’ IRA/Sinn Fein in the aftermath of the 1918 election – ‘armed republicans had been made legitimate once more.’ In fact, the Provisionals got only 35 pet cent of the Catholic vote (even in the heightened atmosphere of the time) and Conroy ignores Sinn Fein’s subsequent disappointing performance in Northern Ireland, and its derisory performance in elections in the Republic. While Conroy’s bias may be un-self-conscious or understandable, and his presentation of the Sinn Fein line a legitimate exercise in itself, his book would have benefited from greater self-awareness or greater honesty. Its virtue is to have drawn further attention to a community whose alienation and despair are at the core of the Northern Ireland problem, and whose ghettoisation has been as much connived at by the authorities as it has been exploited by the Provisional IRA.

Send Letters To:

The Editor

London Review of Books,

28 Little Russell Street

London, WC1A 2HN

letters@lrb.co.uk

Please include name, address, and a telephone number.