‘What are you?’ As far as I remember, these were the first words ever spoken to me by an Ulsterman. Well, an Ulster child, actually. We would both have been about seven years old and it was my first day at school in the province. I’d previously attended a preparatory school in Cambridge and another in Dunfermline, but neither had prepared me for the question so abruptly shoved in my face that morning. In form it seemed grandiosely philosophical, a rhetorical gesture in the ‘What is the stars, Joxer?’ tradition. But the tone of voice – down-to-earth, menacing – belied that idea. I wasn’t sure what the question meant, but I was left in no doubt that the wrong answer would have unpleasant consequences.

‘I’m English,’ I admitted grudgingly. My Scottish schoolmates had made the most of having a real live hostage to re-fight history with. You could see them thinking: ‘This time, do we get to win?’ Hell yes, and next time, and the time after that. I was just wondering how I could contrive to be ill for the rest of the year when the boy replied: ‘Oh fair enough. You’re one of us then.’ His accent was so thick and gritty it was some time before I understood the words. The sense continued to elude me. One of them? Presumably he was being cruelly sarcastic.

About the same time, my mother was stopped in the street by a neighbour and asked: ‘Is your husband a black man?’ Not only were blacks as rare in Ulster as Albanians, but the neighbour in question was well-acquainted with my father’s appearance. ‘No, he’s English, actually,’ my mother replied, to which the neighbour returned: ‘Is he walking the day?’ ‘No,’ was the faint reply, ‘he’s gone by train.’ They parted amicably, each thinking the other was crazy.

My mother’s neighbour was asking whether my father was a Black Man – that is, a member of a Protestant Masonic Lodge (cf. Orangeman) whose ostensible purpose is to process up and down in fancy dress (‘walking’) accompanied by flute bands and 17th-century war drums, but which really exists to maintain the Protestant stranglehold on all financial and professional services within the province and to ensure that however high the rate of unemployment in their community, it’s twice as bad for the Catholics. In Ulster we ‘English’ (i.e. mainland Brits) are not just any old foreigners. We’re ‘one of us’.

Returning to the province for the first time in twenty years, I was apprehensive. When I lived there Belfast was as little-known as Lerwick before they discovered oil. Most people ‘across the water’ had never heard of it. Those who wanted to see it for themselves mostly took the steamer from Liverpool. The crossing is notoriously rough and lasts 11 hours, which half the boat spend knocking it back and the other half throwing it up. This leaves Belfast facing a deficit of good will and may be one reason why the city has never enjoyed a good press (although Joyce, oddly, claimed to like it). As hardened a traveller as Paul Theroux emerged wild-eyed and spluttering: ‘I knew at once that Belfast was an awful city ... demented and sick ... a hated city ... one of the nastiest cities in the world ... the old horror ... a city of drunks, of lurkers, of late-risers ... the blackest city in Britain, and the most damaged.’ Even for a writer whose favourite spot in the kingdom appears to have been Cape Wrath those are strong words, but I was quite prepared to believe them. Everything I had heard suggested that the place had been gutted and boarded up, with no one but a few violent squatters living in the ruins. It sounded like Beirut, only with lousy weather.

At first I was surprised at how little had changed. The Ben Tre school of urban planning (‘It became necessary to destroy the town in order to save it’) has of course left its mark here as elsewhere, notably in the form of one-way systems of the kind Birmingham recently took to their logical conclusion when the city was turned into a race-track. But despite all the free demolition work by the two rival firms, the Seventies have dealt relatively lightly with Belfast. Perhaps the planners feel the place has suffered enough. The worst eyesore is the Europa Hotel, a charmless tower block with precisely the air of prawn-cocktail-and-Mateus-rosé sophistication that the name suggests. For this, the stately GNR terminus was sacrificed. But the Crown Liquor Saloon opposite, the San Marco of pubs, is not only still there but protected by the National Trust. I was apprehensive of what I might find inside. Diary of an Edwardian Country Lady beer mats? A glass cover over the ‘genuine’ sawdust sweepings? But conversation in the massively intimate snugs was anything but hushed, and the punters (lurkers and late-risers every one) standing around in the polychromatic magnificence of the tiled bar had eyes only for the television suspended from the ceiling, relaying the 4.30 at Catterick.

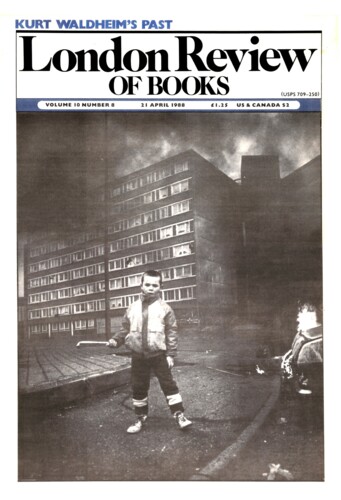

Outside, the soft warm rain, as if the air had grown fur, proved itself still capable of soaking you to the bone in minutes, while the grey sky was in a class of its own, as far superior to the English model as those of Provence are to its blue. Because of the Emergency, vehicular access to the centre is strictly limited and any unattended parked car likely to be blown up. This drastic but extremely effective tactic has transformed the city centre into a de facto pedestrian precinct, and the broad Edwardian thoroughfares can be seen for the first time more or less as their builders intended. The place looks oddly prosperous, too, no doubt because of the extra money being pumped in for political reasons, and the local arts scene is healthier than in most mainland cities of its size. Belfast will never be the Athens of the north, but compared to Dublin, which is looking more like its Naples all the time, it seems trim and buoyant, with an almost manic optimism in the air, the irrational euphoria of the survivor. If our towns, like the French, adopted the custom of listing their attractions – Son plan d’eau, sa piscine municipale – then Belfast might well emulate the village I once saw whose sign, whether in defiance or desperation, read Son futur.

What will that future be like? It was fine for a while to play the Jamesian flâneur, revisiting old haunts and erecting personal blue plaques, but Belfast has what the Master might have called the ‘happy knack’ of rubbing your face in reality. There was lots to read, for one thing. In Britain the churches have realised that to advertise effectively you must adopt the discourse of advertising: you’re not just competing against rival products but, crucially, against rival messages. The result has been ‘Thoughts for the Week’ couched in the soft insinuating tones of a British Telecom ad: ‘When God answers your prayers don’t forget to say thanks.’ Ulster churches disdain such tactics; they would no more think of second-guessing the Deity than Stanley Wells would of paraphrasing Shakespeare. The result is that pure blasts of 17th-century English peal out amid the High Street mix, creating acute problems of harmonisation. John Julius Norwich pointed out that St Paul can sound like Nancy Mitford (‘How shall not the ministration of the spirit be rather glorious?’), but dropped beside a Benetton hoarding on the Divis Road the Apostle might have been writing copy for a competitor to Jesus Jeans: ‘When anyone is in Christ he is a new creation.’ As happens elsewhere, some posters have been edited and footnoted, with unusual results. The mainland eye, sighting a sticker over the bikinied model advertising vodka, expects to be reminded that this sort of thing degrades women. But the sticker reads: ‘No booze in hell.’ Lay off the lager for the duration, lads, there’s draught champagne in heaven. Every surface admonishes or chides. ‘Saved or Lost,’ a lamp-post comments as you pass. ‘Christ is Love,’ opines a small metal plate nailed to a tree. ‘The fool hath said in his heart: There is no God,’ thunders a motorway retaining-wall. But it is not these fools who are the real problem in Ulster, as the walls’ harsh chant reminds you. ‘No Pope here’ and ‘Paisley For Ever’ are the Loyalists’ battle-cries, and the whole business is summed up in this pairing of two men who are not only virtually indistinguishable physically – that air of sleek taurine menace – but share the same reactionary opinions on almost everything except the question of whether salvation is awarded on the basis of continual assessment or a final exam.

All this was more or less as I remembered it. But there was a new element: walls reading ‘Ulster says No,’ ‘Ravenhill Housing Association says No,’ ‘Ormeau Bakery says No,’ ‘Jim and Brenda say No.’ The immediate target of this chorus of noes is the Anglo-Irish Agreement, but to see them gathered there, obdurately refusing and denying on every side, is to be reminded of the core mentality of the Ulster Protestants. As my train from Dublin arrived, it was stoned by a gang of teenage Loyalists. Why? Because its daily appearance in the city tends to throw doubt on their vision of Ulster as a large island moored in the Firth of Clyde. Similarly, their determination to destroy the Hillsborough Agreement has nothing to do, in the first instance at least, with any fear of its possible consequences, which is why it is useless offering reassurances on this point. The Agreement’s sin, like that of the Dublin express, is original: it acknowledges that the Irish Republic exists.

This intense negativity colours every aspect of Loyalist behaviour, even its manner of killing. The Republicans go in for gory public shows, an exuberant but impersonal display combining maximum publicity with the minimum risk to themselves. The Ulster poet James Simmons has captured this.

Familiar things you might brush against or tread

upon in the daily round were glistening red

with the slaughter the hero caused, though he had gone.

By proxy his bomb exploded, his valour shone.

That mythic scale, those dramatic gestures, are rarely found in Protestant violence. Their style is relentless, tight-arsed, confrontational. At the pub opposite the house where I was staying – the terraced houses drawn up like soldiers on parade, decorated with union flags and bunting, the curbstones painted red, white and blue – a suspected UDA informer had been done to death a few months earlier. His killers had stretched him out on the floor in a back room and then dropped a concrete building-block on his head over and over again. It sounds like a black joke: ‘Your man just couldn’t get it through his head which side he was on.’ ‘Thick as a brick, thon same fella.’

‘You’re one of us then.’ In Scotland I was made to pay the price of history: in Ulster I reaped the dividends. The boy who asked me ‘What are you?’ recognised only two possibilities. My being English made me ‘one of us’: a Protestant like him. The fact that my father was agnostic and my mother a Quaker had nothing to do with it. The WEA lecturer who said he was an atheist was promptly asked: ‘A Catholic atheist or a Protestant atheist?’

The Italian humorist Achille Campanile, whose gentle civilised work deserves to be better-known abroad, has a story called ‘Quel generale romano’ about the Roman general who earned himself a niche in history by ordering the execution of his own son for disobeying an order, even though this disobedience had resulted in victory. ‘As your father I embrace you,’ he is reported as having said, ‘as your general I sentence you to death.’ What an admirable example of rectitude and firmness! On the contrary, retorts Campanile. By neglecting to discipline his disobedient son the man demonstrated what a poor father he was; by condemning a brilliant soldier he proved himself incompetent as a general as well. How much better for his reputation – to say nothing of his son’s health – if he had chosen to wear his two hats the other way round: chastise his son for his insubordination and then congratulate his junior officer for winning the battle. Excessive indulgence comes as easily to a parent as excessive severity to a military man, Campanile concludes, but what is easy is never admirable.

Like that Roman general, we have always got our priorities in Ulster wrong, gone for the easy solution and then pretended that it was tough but correct. We have been militarily strong and politically feeble. The province is economically dependent on Westminster, yet we have never seriously used our influence to apply pressure to the Protestant community. On the contrary, we have consistently allowed them to define the terms of the conflict in such a way that no peaceful settlement is possible. Our easy choices have provoked easy reactions, to which all the deaths have lent a certain spurious dignity. But the cruellest feature of such atrocities as Enniskillen is that they make no difference. Just as most criminals vote Conservative, reflecting their conviction that the redistribution of wealth is best left to private enterprise, Ulster terrorists – both ‘ours’ and ‘theirs’ – share a vested interest in preserving the status quo. What is finally most sickening about their violence is its bad faith. It’s easy to kill for a cause, but solutions have to be worked at. As it stands, the Anglo-Irish agreement represents a modest but long over-due start to that work, rather like the symbolic turf turned over with a silver spade by the mayor. The real digging is still to come.

Send Letters To:

The Editor

London Review of Books,

28 Little Russell Street

London, WC1A 2HN

letters@lrb.co.uk

Please include name, address, and a telephone number.