‘La France Libre,’ de Gaulle wrote to Jean Marin, who’d been his companion in London from the summer of 1940 and was now the Director of the Agence France-Presse, ‘that was the finest thing we ever did.’ He believed this. Many of his closest associates believed it too. But as the leader of la France Libre (and la France Combattante), de Gaulle was hardly a free man. Dependent on British money, controlled in his utterances by the Foreign Office and the BBC, at the mercy of a hundred intrigues and rumours, watched by the critical and grudgingly admiring Churchill and by the hostile and non-comprehending Roosevelt, de Gaulle was forced to fight battles which were not of his choosing and usually far removed from his own more grandiose preoccupations. The man who defined his objectives by consulting the globe rather than a mere atlas was too often reduced to scrutinising an agenda that had been prepared by British civil servants. It was only in 1958 when he was elected President of the new Fifth Republic that he was able to exercise a power and to enjoy a prestige that were free both from the supervisions of foreign governments and the constraining confusions of the Liberation. It is true that he continued to see his legitimacy as deriving as much from the achievements of June 1940, when he carried with him to London both the sovereignty and the honour of France, as from the vote of 21 December 1958 when a restricted electorate chose him as President. It is true, too, that when he took up residence in the Elysée Palace in January 1959 (he would have preferred Vincennes, Versailles or the Invalides, anywhere on the Left Bank, because, he said, ‘you don’t make history in the eighth arrondissement’), he brought with him those who had been his companions in London or who had followed him in the unsuccessful adventure of the Rassemblement du Peuple Français, men such as Geoffroy de Courcel, Pierre Lefranc, Jacques Foccart or François Flohic. The Fifth Republic was not to be a resuscitation of the headquarters of Carlton Gardens or the Rue de Solférino, however. De Gaulle surrounded himself with what were for him new men, some of them products of the recently-created Ecole Nationale d’ Administration. In spite of a pessimism that was both innate and a natural reflection of the fact that he was now 68 (‘I’m ten years too old,’ he used to say and he was constantly haunted by the spectre of the senile Pétain), he created the machinery for a new and lasting type of Presidency. He established the role of the President under the new constitution and he indicated the part that France would play in Europe and the rest of the world. It is these impressive and significant years which Jean Lacouture now describes.

Although Lacouture surrounds his subject with a degree of awe, and frequently refers to him not by name but as le Souverain, le Monarque, le Connétable, le Vieil Homme de l’Elysée, le Géant, so that one might almost talk about the divinity that doth hedge a general, it is nevertheless made clear that nothing was easy for de Gaulle. For example, Lacouture argues that de Gaulle had always accepted the need to establish some sort of independent Algerian state, but what he emphasises are the obstacles which he had to overcome in order to achieve this objective. The head of his Cabinet Militaire at the Elysée, General Grout de Beaufort, a believer in Algérie Française, was in charge of all communication between de Gaulle and his military leaders. Within the government only Couve de Murville, the Minister for Foreign Affairs, was prepared to declare publicly that there was no alternative for Algeria other than independence. Several ministers, such as Jacques Soustelle and Bernard Cornut-Gentille, were in favour of the integration of France and Algeria. Most important of all, the Prime Minister, Michel Debré, and his entourage, were prodigal with their assurances that the President would never even contemplate abandoning Algeria. After the anti-de Gaulle rising of 1960, known as the affaire des barricades, the General decided to change the minister in charge of the Army. He persuaded Pierre Messmer to take the other man’s place, but advised him to go back home and not to see anyone, for now, he said, ‘I will have to persuade the Prime Minister.’ De Gaulle was also well aware that his old friend from Saint Cyr, Marshal Juin, one of the few people who addressed him as tu, was violently opposed to any weakening of the links between Algeria and France. It was the same with Georges Bidault, who had been one of those responsible for his successful return to power.

It is not surprising that de Gaulle should have suffered from exasperation and discouragement more often than is generally thought. One such occasion occurred in May 1962. General Salan, one of the leaders of the unsuccessful putsch in Algiers the previous year and now the leader of the Organisation Armée Secrète which was trying to foment civil war, had been arrested and put on trial for his life. His lawyers turned his trial into an attack on de Gaulle, and Salan got off with a prison sentence. De Gaulle was receiving the head of an African state at the Elysée when he heard the news. White-faced, he retired immediately to his private apartments where his aide-de-camp found him profoundly depressed and offended. It was the revenge of Vichy, the triumph of the colonialists, an affront to the state. Salan’s subordinate in the insurrection, General Jouhaud, had been condemned to death though it had been understood that de Gaulle would use his right of pardon in Jouhaud’s favour. Now Jouhaud would have to be shot.

Pompidou, who was now Prime Minister, Foyer, the Minister for Justice, and several other ministers, pleaded with the General. The deputy leader, they argued, could not be executed if the leader was only to be imprisoned. But de Gaulle would not give way and if Jouhaud’s lawyers had not managed to obtain a stay of execution on a point of procedure, then Jouhaud would doubtless have gone before the firing-squad. At Colombeyles-deux-Eglises, de Gaulle was pessimistic. He refused to leave his house over the crucial weekend, even to go to church (Mass was celebrated in his drawing-room), and he inveighed against his ministers, who, he said, had abandoned France. Eventually, Jouhaud’s lawyers persuaded him to make a declaration from his prison-cell, advising his fellow members of the OAS to abandon the struggle. De Gaulle accepted that such a statement could be important and that, once it had been made, it would be advisable not to execute Jouhaud. However, five months were to elapse before his decision was made official. ‘Je reviens d’un long voyage,’ Jouhaud said when he left his death-cell and proceeded to prison at Tulle.

Lacouture sees much that was typical of de Gaulle in such episodes: his contrariness – he was never better than when he was refusing to give way; his grasp of the political nature of a problem, which led him to underestimate military exigencies; his desire to experiment, and to test public opinion by carefully chosen and timed pronouncements. Most important of all, in Lacouture’s view, were the everlasting principles of gaullité, according to which everything in the world changes and the only reality is the nation-state. This meant that the Franco-Algerian structure of the 19th century was not intended to persist into the second half of the 20th century: that a country inhabited by Moslem Arabs and Berbers was not France. Perhaps Lacouture goes too far when he claims that everyone should have understood that these were his guide-lines and suggests that misunderstandings arose because de Gaulle’s policies were distorted and misrepresented by his Cabinet Militaire and by the Prime Minister’s associates at the Hôtel Matignon. De Gaulle’s manoeuvres required a certain amount of ambiguity, and since he was not certain what would be the exact relationship between an independent Algeria and France some confusion was inevitable.

This is not to say that Lacouture is uncritical of de Gaulle. Although he follows closely, too closely perhaps, de Gaulle’s unfinished memoirs of this period in office, as well as the recollections of devoted Gaullists such as Commandant (now Admiral) Flohic and Pierre Lefranc, he allows himself a few comments of his own on the Algerian affair. Thus, like his friend Pierre Mendès France, he seems to think that de Gaulle did not do well in the negotiations with the FLN, that he was too anxious to get a settlement to be able to hang on for a better agreement, alternating pressure and concession at the expense of the intervals that existed between these extremes.

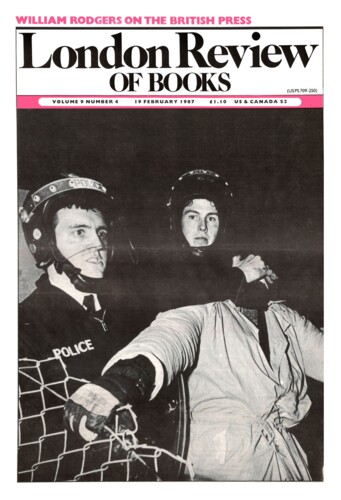

In January 1962, incensed by the murders which the OAS were committing in Paris, the left wing, mainly Communists, trade-unionists and students, organised a massive demonstration against them, and against what they saw as the passivity of the Government’s response. The demonstrators were attacked by the police and, as we now know, by agents provocateurs from the OAS. Such was the violence of the attack that nine demonstrators, including three women and a child, were crushed to death in the entrance to a metro station. There was no official inquiry, and de Gaulle, not regarding it as a concern of the state, kept silent. Perhaps, Lacouture seems to be saying, he was strictly speaking right to do so, but he wonders how this has affected de Gaulle’s reputation – sa gloire, pourtant?

It was in August 1962, at Petit Clamart, that the OAS made their attempt to assassinate de Gaulle: nearly two hundred bullets were fired at the car in which the General and his wife were travelling. The signal for the attack had been given by the man who organised the ambush, Lt-Colonel Bastien-Thierry, who waved a newspaper when he saw the Presidential car approaching. This was one of the reasons de Gaulle insisted that he be shot: he had not taken any risks himself, had not been involved in the shooting. The two active would-be assassins were pardoned. Lacouture comments on the strange legality of this argument, and quotes de Gaulle’s comment:

The French need martyrs. I could have given them one of those cretinous generals, but I gave them Bastien-Thierry. They can make a martyr of him. It serves him right.

No one, the biographer remarks, emerges unscathed from all this. Not even le Connétable.

Lacouture has organised this volume differently from its two predecessors – one on de Gaulle during the war and the other covering the period from 1946 to 1959. He has given up strict chronological narrative and, instead, treats three major themes separately: Algeria, international affairs, and de Gaulle and the French people. This is clearly wise, given the immense detail that burdens these years. It also allows Lacouture to comment directly on the issues, which he does more readily in the matter of foreign and domestic policy than he does on the Algerian crisis. So many of the episodes which he discusses have already been the subject of innumerable accounts that there is nothing new to add, and the biographer’s task is to put them into the perspective of an overall judgment. It is true that he has spoken to many of those who were directly involved (although neither the General’s son, Admiral de Gaulle, nor Michel Debré seem to have assisted him directly), but by and large it is the immense published literature that has enabled Lacouture to produce his portrait of this si prodigieux personnage, as he calls him. Knowing, as many French writers do not, what British and American specialists have said about de Gaulle’s policies, he is inclined to be more sceptical of his apparent successes, while savouring the energy, persistence and style which the General always had.

Naturally the three themes chosen cannot be completely separated the one from the other. In March 1962 when the Fouchet Plan for reforming the European Community was being discussed, Louis Joxe was negotiating with the Algerians at Evian. The Europeans were conscious of the fact that once the Algerian war was over the General would be able to devote all his assertiveness to European affairs. The Europeans were right. In January 1963, he put an end to British attempts to negotiate their entry into the Community: was this in order to demonstrate that his hands were no longer tied and the world should know it? In 1965 Walter Hallstein, acting on the advice of Jean Monnet, thought that the moment was favourable to increase the powers of the European Commission and thus take a step towards supra-nationality. The bribe that he offered the French was the subsidising of agricultural products, which would please the farmers whose votes de Gaulle would need in the Presidential elections of December 1965. But de Gaulle refused to be manoeuvred in this way, and riposted by withdrawing the French representative from the discussions in Brussels.

Lacouture tries hard to be fair as he describes these events, explaining that although de Gaulle did not like Great Britain, he admired the British. He recalls that the British mistrusted him, claiming that beneath his Presidential suit (as seen at Westminster in 1960) they could discern the general’s uniform; that British public opinion was against joining the Community; that the Kennedy offer on Polaris was more favourable to Britain than it was to France; that the British, anxious to join a Community they had tried to stifle at birth, were ill-advised to insist on changing the rules of that Community. But Lacouture wonders why, given his sense of England being a Trojan horse within which an all-invading America was hiding, de Gaulle should have made the Federal Republic his privileged ally, knowing as he did how much Germany depended on the USA. He notes, too, that with the breakdown of the attempt to establish a supra-national authority, the Community slowly turned into the sclerotic bureaucracy which today inspires so little enthusiasm. For once, de Gaulle’s wit fails to amuse him. Presiding over a Cabinet meeting in December 1962, de Gaulle explained to his ministers that he had been unable to offer any comfort to Prime Minister Macmillan at their meeting in Rambouillet; he had felt, he told them, like putting his hand on the shoulder of ‘ce pauvre homme’ and saying: Ne pleurez pas, Milord. Not, Lacouture remarks, the best of de Gaulle.

There are many passages which will not please the General’s very many faithful admirers, all of whom, even the Socialists among them, are now sporting badges that say: Ne touchez pas à mon de Gaulle. But there is never any doubt: admiration prevails even if it stops short of idolatry. It is evident in the discussion of de Gaulle’s final years and his relations with Pompidou. In 1968, having decided that he would after all stay on as Prime Minister, Pompidou was angered and humiliated to be told, by telephone, that the General had asked Couve de Murville to replace him. Was it not natural, Lacouture asks, that someone who repeatedly expressed his wish to resign should have that resignation accepted? Besides, Pompidou had said many times that he had reservations about the social reforms which were to follow the upheavals of May 1968 and had formed un clan pompidolien among the Deputies, which was not to the General’s taste. Lacouture puts his trust in Couve de Murville, who has told him personally that he was never offered the post of prime minister before July 1968 and that he suggested that Pompidou stay on for another six months. Lacouture also believes that it was de Gaulle’s liking for antithesis which led him to replace the jovial, talkative peasant from the Auvergne, now part of the Parisian avant-garde (abstract in painting, concrete in music), by the tall Protestant who read Victorian novels and who seemed to be fixed dans un understatement perpetuel. The one seemed to come from Jules Romains’ Les Hommes de Bonne Volonté, the other from a novel by the puritanical Gide.

Pompidou’s resentment persisted and was fuelled by further unfortunate incidents. De Gaulle died on the evening of 9 November 1970. His son arrived in Paris early the following morning. Although Pompidou, now President of the Republic, knew of his whereabouts, he made no attempt to get in touch with him. It was Pierre Lefranc who went to the Elysée to discuss the funeral arrangements. The President announced that he could not go to Colombey that day. It would have to be the following day, or the day after that. Then he changed his mind and said he would go that afternoon, But Madame de Gaulle refused to see him. There were two funeral services. The first was at Colombey, where the coffin was carried by six young men, the sons of farmers. The second took place at Notre Dame in the presence of the world’s leaders and there was no coffin. In the preface to Le Fil de L’Epée, written in 1932, de Gaulle quotes (or misquotes) Hamlet: ‘To be great is to sustain a great quarrel.’ For de Gaulle, a ‘quarrel’ was essential for his mission – the pursuit of greatness for himself and for France.

Send Letters To:

The Editor

London Review of Books,

28 Little Russell Street

London, WC1A 2HN

letters@lrb.co.uk

Please include name, address, and a telephone number.