The Mende are a forest-dwelling West African people, numbering about a million, one of the two principal ethnic groups in Sierra Leone. They owe their existence to the 16th-century diaspora of the Mande-speaking inhabitants of the Mali Empire and the incorporation by these conquering bands of a number of small coastal tribes. Mende history until the colonial era is one of raiding and slave-holding, their economy is agricultural and their traditional religion the veneration of ancestors and nature divinities under the aegis of a creator god. They do not figure largely in ethnographic literature, nor in accounts of African art, though their highly polished black wooden masks are found in many collections. Radiance of the Waters, in fact, is only the second book to be written about them (the other is by Kenneth Little, an anthropologist whose The Mende of Sierra Leone first appeared in 1951).

Why this comparative neglect, this failure to engage the attention of scholars? Is it due to the peripheral position of the Mende among Mande-derived cultures – the fact that they have only existed as a distinct entity for a few centuries? Is it because they are eclipsed in significance by the Akan of Ghana, the Yoruba of Nigeria – the high civilisations of the West African coastal region? Or is it that the Mende are a dull people whom no one wants to study? Sylvia Ardyn Boone doesn’t consider any of these questions. Her own explanation for the dearth of Mende ethnography is the secretiveness of the people themselves, and their intense hostility to researchers, a hostility that is all the greater when the researcher is one of their fellow tribesmen. She tells the story of the Reverend Max Gorvie, a Mende who wrote two small books on Sierra Leonean laws and customs which were published by the Society for Christian Literature in the 1940s. Gorvie was driven out of the country for his pains, returning only after 27 years’ exile and living out his life in self-imposed expiatory silence. It is now nearly impossible, reports Boone, to find copies of his books in libraries: they are removed by traditionalist Mende who feel duty-bound to preserve the secrets of their culture.

Reading Our People of the Sierra Leone Protectorate (1944) or Old and New in Sierra Leone (1945) – copies of which remain intact in the British Library – it is hard to see what the Mende could find objectionable in Gorvie’s brisk run through their history and folklore, unless it is his references to clitoridectomy or the mention of the ‘baneful cannibal palaver’ formerly practised in Mendeland. The Mende objection to published descriptions of their way of life seems to be a general one. They believe, according to Boone, that information about Mende society should not be transmitted to those not subject to its laws. Such information, accordingly, is concealed and the outsider sees, at best, darkly. An aptly numinous Mende proverb has it thus: ‘There is a thing passing in the sky; some thick clouds surround it; the uninitiated see nothing.’ Mende costiveness extends to their own kin. There is hardly a Mende, writes Dr Boone, without a tale of something lost – buried coins, herbal formulae, artistic technology – because the treasure’s owner found no relative deserving enough to inherit it.

It is not surprising to find that traditional Mende life is dominated by secret societies, one of which, the Sande women’s society, is the particular subject of this study. It does seem surprising that Dr Boone, whose tone is one of rapt admiration for the ways of Mende and who shows an exaggerated respect and affection for the ‘wise women who are the leaders of the Sande society’, should feel free to flout its fundamental prohibitions by publishing a book about it. She makes it clear, though, that she had the co-operation of prominent figures in the cult: indeed the book is presented as a ‘partial fulfilment’ of her promises to Mende elders (who remain, nevertheless, with one exception, anonymous). What we have, in fact, is not a revelation of the mysteries of Sande, but a respectful approach to them, by an art historian who has tiptoed where anthropologists feared to tread. She found, she said, that Mende women were willing, even keen, to talk about ideas of female beauty, but she could not ask direct questions about the cult itself. In her account of the bush schools where Sande ideals of womanhood are realised, she plays down the feature of the ritual that is liable to set Westerners’ teeth on edge: clitoridectomy is mentioned only twice, despite being the rite de passage which all Mende girls must undergo.

Radiance from the Waters deserves to be read, however, before it is removed from the shelves of the library by some tradition-minded Mende striving to keep it out of the hands of hoi polloi. It provides something more interesting than esoteric knowledge: an extended meditation on notions of beauty and decorum and the way in which these can be translated simultaneously into art and advancement – advancement for women in a society where the odds are, as ever, in favour of men.

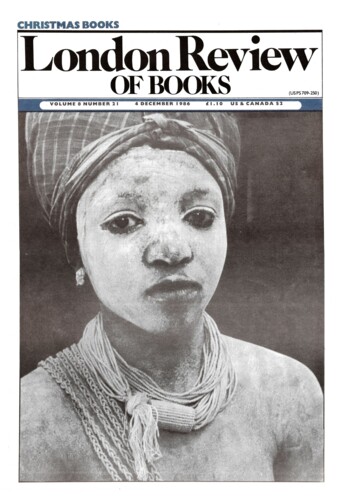

Men get hardly a mention in this book: their role is only to manufacture the aubergine-smooth Sowo masks that are used in the rituals of Sande. To the outsider these masks appear enigmatic: shiny black helmets carved in a style both precise and exaggerated, featuring huge domed foreheads and fleshy necks, sharp-featured faces with pursed mouths and half-closed eyes, heads surmounted with elaborate coiffures. They are plump masks, alluring but uninformative, without the distortion that excited the Cubists, and assimilable to Western taste only at the tactile level. But for the Mende these masks represent the ideal female form. In their art, beauty is the preserve of women; only the female face is represented. Men are consumers of beauty, not producers. If a man is handsome, Mende say: ‘He is like a woman.’ They also say: ‘Nothing that has a vagina can be ugly.’ By comparison of the aesthetics of the Sowo mask with archetypes of human beauty and by descriptions of the bush schools, where Mende girls are secluded from male society in order to learn the requirements of womanhood, Boone is able to show in some detail the significance of these masks in Mende aesthetics.

Mende women like to have breasts like calabashes, broad and saucerlike. They like to have generous buttocks that roll when they walk. They like to have fat necks, tight vaginas, gap teeth and small noses (the nose is the only European feature they admire). Lips, they believe, should be red like the vulva (which they call ‘the mouth found underneath’), but they should be kept closed – this indicates discretion, a virtue that the Mende, as we have seen, value above all others. They like high foreheads and tight-braided head hair. Men and women shave their genitalia, but they are divided over the desirability of hair under the arms. Most Mende have skin that is dark brown, but they prefer copper or jet-black, the colour of the mask and they dye their hair black with indigo. Conversely, girls undergoing initiation paint their faces with white clay. They are, like most African peoples, obsessively clean by Western standards. They even insist (impossibly, since half of them do not wear shoes) that the soles of a person’s feet should always be clean.

The purpose of the Sande bush schools seems to be to inculcate these values into Mende girls. The syllabus includes deportment, singing, dancing, the knowledge of flowers and herbs, and ritual surgery. The regime is strict. The dance mistress may use shock techniques on novices, waking them in the middle of the night and ordering them to dance, or forcing them to stay awake for two days and nights, dancing all the time. It’s tough, but not as tough as being a Mende child. Mende children have such a bad time that the Sande summer camp must seem like paradise. Before they go there for initiation Mende children are constantly chastised and neglected, frequently beaten or bullied and deprived of food. They are, says Boone, non-persons without rights, often sent as bond slaves to the households of men of influence to repay a debt or return a favour. The moment they are initiated they are free of this bondage. For a girl, one could say, to lose her clitoris is to gain her humanity. The Sande system ensures that she undergoes a simultaneous indoctrination in Mende ethics and aesthetics. In the seclusion of the women’s society, under the clay maquillage, the mask of adulthood is forged, with the Sowo mask as template.

The Mende prohibition on the dissemination of knowledge can be seen as a preservation of this ceremony of innocence: the keeping not of a secret but of the condition of secrecy, a state where the soles of the feet can be clean and nothing with a vagina can be ugly. If the connections made in this book between the ritual state and the art that epitomises it are sometimes obscure, it is because Dr Boone has incorporated aspects of Mende discretion and circumlocution into her own thought. This may indicate a proper, i.e. a Mende, restraint. We see a form of life only half-revealed, but this, after all, is as much as wisdom dictates for anyone. And for a society such as this, whose tribal culture is pincered between Islam and Christianity, it is a technique of self-preservation.

Send Letters To:

The Editor

London Review of Books,

28 Little Russell Street

London, WC1A 2HN

letters@lrb.co.uk

Please include name, address, and a telephone number.