Every morning as I woke up I reached for my radio. A cheerful Home Counties voice announced: ‘Sunny skies in Buenos Aires, Toronto, Calgary and Tokyo: overcast in Dublin, Rome and Ankara: rain in London, Athens, Nairobi and Frankfurt.’ As South Africa gets the weather, so it gets its news: in gobbets of fact, fragmented beyond all hope of comprehension.

There are items that the news loves. They are, top, world disapproval of South Africa, then corruption in black countries, sporting events of all kinds in all countries, speeches on terrorism by foreign politicians; internally, the collapse of a strike whose beginning was never reported, the opening of a trial of which nothing more will be heard. When news turns to comment, anonymously delivered, cheerfulness gives way to the rasping tones of common sense. ‘South Africa, whose feet have now been set irrevocably on the path of reform, will not be deflected by extremists either of the right or of the left.’ The word ‘certain’ carries most opprobrium: ‘certain groups’, ‘certain interests’, ‘certain persons for reasons best known to themselves’, ‘certain ideologues of a Marxist or Westminster persuasion’. A correspondent from London regrets the decay of the relative clause in the speech and writing of the young. Songs punctuate the news to unpremeditated effect: Frank Sinatra, Petula Clark, Victoria de los Angeles, and, one morning, Yves Montand singing the favourite song of the Italian Communist partisans. It is difficult to exclude the external world if you cannot recognise it.

I was in a position to think these thoughts because back in the late Seventies two South African lecturers had come to visit me. They had been friends of the legendary Rick Turner, a brilliant young philosopher who, having gone to Paris to study Sartre and Marx, had returned to teach, had eventually been banned by the authorities, and, answering the front-door bell one morning, had been shot dead. That had been a year or so earlier. They talked to me of the isolation of the Left and the reinforcement of the Right by touring lecturers from Baptist colleges in the Southern States of America. If I ever had the chance, would I please go? When I went last month I was not prepared for what I found: for the splendours or for the miseries.

Superficially the University of Cape Town is like a Californian campus. It has a magnificent site, which it has done quite a bit to spoil. The faculty have been to foreign universities. The students are intelligent and eager and believe in showing it. The ideas that circulate come from France and America. Posters advertise protest marches and shared rides home and lectures and water-skiing equipment; they denounce the Police and nuclear energy and conscription. There is more theology than there would be in England. Out of ten thousand students, two to three thousand (I was told) are radical, five hundred, of whom next to nothing is heard, support the Government, and the rest are in the centre and occupied with life’s ordinary ambitions. Fifteen per cent are non-white. But if all this approximates to California, there are two big differences. For the first difference you would have to imagine the airport functioning, say, one day a month. People do come and go, but with a meagreness which is out of keeping with the modern world. Students carry around not books but xeroxes of chapters of books that by now no one can afford to buy. And the second difference is that the more amusing-looking students, the elegant kids, who don’t give the impression of having just come off the sports field, who wear a touch of ethnic clothing or T-shirts demanding the release of Mandela and gold and silver chains and bracelets, whose hair is slightly longer if they are girls or slightly shorter if they are boys – these students lay, perhaps not their lives, but certainly their safety on the line.

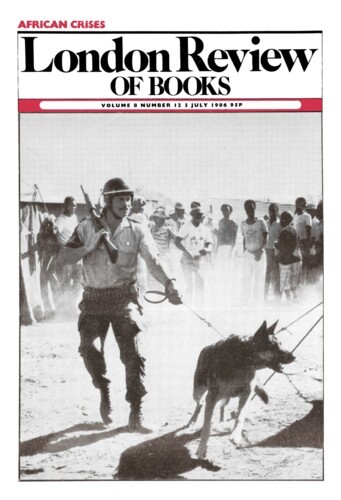

I had the chance of seeing the Police in action on the campus. It was nothing, people tell me, compared with last autumn or ten years ago. It was nothing compared with what I had seen at Minneapolis in 1972. It was the reaction-time that was special. Three or four hundred students had gathered on Jameson Steps to denounce the cross-border raids. After discussing and voting on every issue of tactics, they followed their elected leader, one of the students who had been to see the external ANC, across the edge of a rugger field, down to the verge of the freeway. There they shouted slogans and held up their placards to passing motorists. A police officer in shirtsleeves, with that walk parodied in Woza Albert in which the body bends from the ribcage, strolled over to the central divider and spoke inaudibly through a megaphone. ‘Here it comes,’ the shout went up barely a minute later and an armoured vehicle raced along the freeway spraying the students and the grass with blue liquid. Tear-gas was fired into the crowd, and police, appearing from behind, where they had been hidden, chased the demonstrators into a narrow area lined with long glass windows. Re-forming, the students vowed to return. But already, drawn up behind an ornamental balustrade, silhouetted against the sky, were the Coloured police, in loose blue fatigues like prisoners, with the monstrous black sjamboks dangling from their hands. Below them a rugby practice continued through the light drifts of tear-gas.

Four students were arrested. Meanwhile, less than ten miles away, a thousand shacks had been destroyed and twenty, twenty-five thousand blacks had been made homeless. I could understand how the children of the middle classes, returning from Crossroads where they did much of the relief work, could resolve to have themselves and their university pilloried and blackguarded and boycotted by the world to the point where their impoverishment, their inner isolation, their humiliation, seemed to approach that which they felt they had connived in imposing on people whom they were not allowed to think of as their fellow-citizens. As far as I could see, in a country which desperately needed ideas not just to effect change but, if it ever came, to consolidate change, this was not the right answer. But it was a response. It showed something that was lacking in the English lecturer who told me that what most worried him about Crossroads was the anarchy.

Everyone by now – everyone, that is, outside South Africa – knows what happened at Crossroads. They know how the authorities, to ingratiate themselves with a compliant and corrupt leader, to get rid of a large and potentially troublesome community, and, as a bonus, to propagate the facile idea that blacks readily show violence to blacks, turned the vigilantes of Old Crossroads upon the miserable triangle of shacks and hovels that lay on its periphery.

I went to Crossroads twice. Once was on my way to the elegant campus of Stellenbosch with a friend who had offered to drive me. Talking to me with pride of his radical children, he revealed the anxieties he experienced as a parent. Would the telephone ring and tell him that his daughter had been picked up by the police? Would his son go to jail for six years for refusing conscription? By now we had left the freeway and we were driving along Landsdowne Road first past ramshackle suburbs, and then, with the Portland Cement Factory to our right, we could see to the left, on rising ground, what looked like the embers of an Australian bush fire. Charred wood, broken bits of corrugated iron, grass long trodden to dust, and pools of water the colour of milk chocolate. At regular intervals young fair-haired soldiers peered out of their troop-carriers to see if somewhere in this scene of desolation there was still the threatening presence of life. By the time of my second visit, which was with a social worker three days later, much of the site had been bulldozed and it was now surrounded with barbed-wire and arc lights. Rain had fallen. At one place the coils had been lifted to allow lorries with protective mesh over the windscreen to enter and clear the junk. Boys, old men, young mothers with four, five, six children in tow, slipped in after them and scrambled up what they could lay hands on and carried it out under the expressionless eyes of the police. What I saw as detritus were the building blocks of the only home they could ever anticipate.

Looking across from where we stood, occasionally jumping back as the police or army drove past swerving through the puddles to splash us with water, I could see the line of trees and bushes that separated Old Crossroads, now in dead ground, from the satellite encampments that had once, a week before, stretched from there up to the road we were now on, and one thing that was clear was that, if the authorities had been concerned to save life and property, if they had merely thought it their duty to maintain law and order, they would have stationed the police, with all the resources that a war economy has placed at their disposal, along that hedge, If – and this is a big if – if the Police are still under control. In South Africa there is much convenient talk about the threat from the right. Foreign media collude in giving the ultra-conservative parties coverage. But, if there really is a threat from the right, it cannot come from these parties, which, in a country where at least five out of six people desire massive change, have been gerrymandered into existence so that a government which has abandoned principle but clings desperately to power can call itself ‘moderate’. The threat, if it exists, comes from the security forces, which can be as readily dismantled as a nuclear power station.

Another thing that was made clear, looking out from Mahobe Drive, was that to the black leaders, standing where they stood, amongst the rubble of their houses, looking back at us up the barrels of the guns trained on them, the appeal for moderation, the call to renounce violence, the invitation to engage in meaningful political compromise, if it ever reached them, was likely to seem in a foreign language. Who asked the Maquis to compromise, or called the July Plot an internecine conflict?

I drove one long afternoon through the heady sensuous beauty of the countryside. I started at Knysna on the Indian Ocean, drove up through forests filled with giant trees, out along the top of a mountain range, through a deep stony gorge, and then across the scrubby desert, past flocks of sheep and large clumps of cactus and red-hot pokers, with the mountains away to the left and right going blue, green, purple, violet-grey as the sun sank, and at nightfall I arrived at the small whitewashed town of Graaf-Reinet, built in a kind of rustic rococo, pressed against the hillside. In half a day’s drive I had passed five cars, and at regular intervals a neat bungalow, which was the farmhouse, and then, about a hundred yards further on, on the other side of the road, a few hen-coops where the labour lived. As my car raced along, sending up clouds of pale red dust, black youths poured out of the forest, or single figures materialised, like mirages, in the solitude of the desert. They thumbed a lift. I did not stop. At one moment I felt tired and wanted to sleep on the verge of the road and wake up to a distant view of mountains. I drove on. Reluctantly I admitted why. Fear, and the fear of fear, kept me going. What conceivable reason, I asked myself, could these people give themselves not to rob me, or kill me, or both? What would restrain me if I were in their position? Only the fear which would not let me stop. In the countryside, under the vast skies of the karoo, apartheid, or segregation, or separate cultural development, or mutual respect for national identity, or whatever is the phrase of the moment, seemed a more inhuman, a more deathly, presence.

At Grahamstown my host threw open the french windows. ‘He loves this view,’ his wife said. From the garden we could see the lights of the town: there the cathedral, there the quiet English-looking university, which now has 20 per cent non-white students, there the leafy, colonial streets. ‘And over there,’ he said, ‘on the hillside the black township. In pitch darkness.’ ‘Have they never had light?’ I asked foolishly. Last autumn they had light. During the unrest the Army stationed itself on the hill opposite, and they beamed searchlights across the town and raked the dirt paths for anyone who stirred. The township had light, night after sleepless night.

The relief was that no one in South Africa said to me: ‘We’re not as bad as you thought, are we?’ No one said ‘we’. They referred to the Government as ‘the Government’ or ‘them’. I remarked on this and someone said to me: ‘That is because you’ve not been to the heart of Afrikanerdom. Even the most radical people there say “we” – say it with shame.’

I never got to the heart of Afrikanerdom. I went to one austere Afrikaans university in the north. There was an exhibition of an incredibly talented black weaver. People asked me how my ideas related to Foucault or Richard Rorty. A painter, Swedish by origin, of great intensity as was his work, talked to me of the problems of South Africa. They were not political problems, he said, they were cultural problems. They were problems of communication and of creativity. The Afrikaner, who could not cry and distrusted his feelings, who was bigoted but without any real conviction, who was submissive to all forms of authority, who felt this hollow in himself, needed the African, but, every time he met one, he was caught up in the same old crude reactions. ‘But with time, with education, with more sensitivity ... ’ Then he told me of how every Saturday he and his whole family spent the day in a Coloured township: marriage-counselling, ecology, Bible-reading, teaching crafts. After two years they started to overcome suspicion, and they were still trying to overcome things in themselves. ‘You have to be able to reach out to these persons as persons to survive the stench.’ It was South Africa’s problems, he and his wife said to me, that were its hope. Purged by its torments, it could become the greatest country in the world.

I never met anyone – though everyone was adamant that I very easily might have – who supported economic sanctions. The poor of South Africa could not tolerate much more poverty: the well-off could. What was needed was massive capital spent in ways that bypassed the Government: on education, on health, on training, on agriculture, on urbanisation, on the transfer of power. Some were more definite, some were hazier, about how this could be achieved. All were aware that on the fringe of such a discussion there waited – and for how much longer? – an ever-increasing body of youth who all their lives had been denied privacy, respect, education, work, and their own leaders. All they had picked up was bitterness and the martial arts. Who except those who had shared their fate could tell them to renounce their only two acquisitions?

On my last day I found in a dusty classroom in Witwatersrand University a copy of the now banned Sowetan, dated 29 May 1986. There was a report of a treason trial in the course of which the counsel for the defence cross-questioned a security policeman about the video of a funeral which the police had confiscated. They had also arrested the crew.

Mr Bizos: Could it not be that the TV crew wanted to show Germany a bit of the truth about South Africa?

Sgt Mong: Is that not propaganda?

Sgt Mong was quite right. The truth about South Africa is its condemnation, and what I had learnt in the three weeks I had been there was the heroism of many people who try to find out, against massive obstacles, massive blandishments, what is the truth about South Africa, and then try to lead their lives in the light of this truth. Someone told me of the exhilaration he felt as a young conscript sitting in the hills above Luanda and hearing the Foreign Minister solemnly swear that not one member of the South African Defence Forces had crossed the border. Loyalty fell away, like an old unwanted skin. It is a heroism that has to be repeated over and over again, and it requires of different people different things: questioning, teaching, standing together, resisting the demands of the state, exposing its lies, perhaps just keeping the forces of life going. The struggle is to build, within the carcass of the present state, an alternative society. If foreign countries can assist these forces of truth and disorder, then they will find something worth doing.

Send Letters To:

The Editor

London Review of Books,

28 Little Russell Street

London, WC1A 2HN

letters@lrb.co.uk

Please include name, address, and a telephone number.