It was the end of a Cabinet meeting and Mrs Thatcher was cross. It was all so silly, so unnecessary. She was half-way through her second term as prime minister – a bad time for most governments, but hers was doing surprisingly well. Earlier in the year, the most dangerous of all the ‘enemies within’, the miners’ union, had been thoroughly beaten in a tough fight. The trade unions everywhere else were humbled and split. The Opposition was fighting itself, and was unconvincing. For a brief moment, almost incredibly, the Conservative Party had established a small lead in the polls.

Now, however, on 19 December 1985, the success and security of her government were banished from her mind by an infuriating, niggling little argument. Once again the Cabinet had been discussing what she described as ‘an insignificant little company in the South-West with a capitalisation of less than £30m’. More than half the meeting had been taken up with a wrangle over Westland Helicopters. It was all most unusual and most irregular: her Cabinet hardly ever discussed individual companies like this. Westlands was an ailing company and Margaret Thatcher’s attitude to ailing companies over the years had been simple and consistent. If companies ailed, if they couldn’t stand on their own two feet, then they would have to go to the wall. There was no room for lame ducks as there had been in the dark days of the Heath Administration of the early Seventies. That government’s slackness towards ailing companies had ushered in all sorts of horrors – strong trade unions, a Labour government. As she had said a thousand times, there would be no ‘U-turn’ for hers. Market forces, she had repeated, were the only real discipline in a capitalist world.

No matter that Westland made military equipment and was therefore not really subject to market forces at all. No matter that the main market in which Westlands dealt was the government market, and that some £750m worth of government orders had been its staple economic diet since the war. Defence industries, too, had to undergo the rigours of the market, and if Westlands was in trouble, it would have to find its own way out, as so many other companies had (or hadn’t). It was of course a pity that Westlands employed 7000 workers, but not such a pity when most of those voted in Yeovil and the Isle of Wight – which had had the effrontery to return Liberal MPs at the last election. If workers were to learn the lessons of unprofitability in a real world, there could hardly have been a more suitable place for them to do so.

These elementary lessons had been automatically applied by the Thatcher Government ever since Westlands first started getting into real trouble at the beginning of 1985. A mixture of old-fashioned British management and plain bad planning had left this famous helicopter company without any orders for a couple of years at least, and with a main new product – something called the W 30 – which no one, not even the Indian Government, wanted to buy. The usual remedies were tried without success. Sir Basil Blackwell departed as chairman with a handsome pay-off. Lord Aldington, a former Tory MP, resigned as president. The colourful Alan Bristow, a helicopter tycoon who had done very well out of flying people to and from the North Sea oil rigs (and by curbing trade unions), made a bid and then withdrew it. By the early summer it looked as though Westlands would go bust. Good riddance, as far as the Government was concerned. When Westland workers or management lobbied the Government – whether the Department of Trade and Industry or the Ministry of Defence – they were lectured about the laws of the marketplace. Good riddance, too, was the message for Westlands from the other big helicopter-makers of Europe. Fewer and fewer helicopters were needed, because fewer and fewer people (or countries) could afford them. There was what businessmen call ‘over-capacity’. Large firms like GEC in Britain, Aérospatiale in France and Messerschmitt in Germany, were licking their lips at the juicy technology and skilled workers waiting to be gobbled up from Yeovil. The prospect seemed familiar. The company would go into receivership. The banks would move in and flog off the assets to the highest bidder. A few thousand workers would join the vast dole queues of the South-West, and the other companies would be able to continue for a short while, making profits in a smaller market until one day the whole process would start again, and a new victim would go to the wall.

In the summer, the Bank of England tried a last rescue operation. Sir John Cuckney, a ‘trouble-shooter’ from the City, was ‘put in’ as chairman to try to sort out the mess. He discovered before too long that there was an alternative to bankruptcy and receivership. The vast American conglomerate United Technologies, and its helicopter subsidiary Sikorsky, indicated that they would be interested in pumping in money in exchange for a mighty slice of the company and a share in its control. A lot of workers would have to go, of course, but production would at least continue for the two years that Westlands didn’t have any orders. The probable result would be that ownership and control would be ceded entirely to Sikorsky, but the company would, after a fashion, survive.

As Sir John disclosed this new plan, he ran into instant outraged opposition from the other big helicopter manufacturers in Europe. They had been happy enough to sit around and watch Westlands go bust. But the prospect of all that technology and skill going to an American competitor was intolerable. The United States of America spends 280 billion dollars a year on what is laughably called its defence requirements. The vast Pentagon buying power (equivalent to the entire product of about three thousand million people in Asia and Africa) is channelled into the largest and richest companies in the world. The bigger these companies become, the more they merge with one another and the more they expand outside American frontiers. Such mergers and expansion are crucial to their survival. As they grow, they threaten the autonomy of companies everywhere else in the world, especially in Europe. The insatiable appetite of these huge American conglomerates is constantly forcing the European defence industries to become huge conglomerates themselves. In this they have been assisted by their governments, who realise that it is difficult to talk about ‘national defence’ if all the European armaments and defence systems are being made by American companies.

These fears quickly grew to panic proportions in the European defence firms as they contemplated Sikorsky taking over Westlands. They were recognised and acted upon by the European governments, including the British Government. Early in October, in letters between the Secretary of State for Trade and Industry, Leon Brittan, and Sir John Cuckney, Brittan made it plain that he supported some kind of initiative from the European defence industries, so that, at the very least, the Westland board would have a choice of courses. These letters (4 and 18 October) have been systematically kept secret by the Government, but their basic content has never been in doubt. Brittan, the son of a socialist doctor, was supported in this enthusiasm for a European alternative by the Secretary of State for Defence, Michael Heseltine. Heseltine was an expert in subservience to the Pentagon. He had enthusiastically supervised the deployment of American Cruise missiles in Britain, and had based his British nuclear ‘deterrent’ policy on the American-made Trident missile. He had just completed negotiations for subjecting pretty well all British defence technology to the Strategic Defence Initiative, more accurately known as Star Wars. But he felt, as Brittan did, that the Sikorsky take-over of Westland could be going too far. He was strongly advised along those lines by his national defence procurement officer, an old friend called Peter Levene whom Heseltine had promoted to high office, in controversial circumstances, at a starting salary of £95,000 a year. Levene had been chairman of United Scientific Holdings, whose recent success had been based to a large degree on the cooperation of the European defence industries.

A meeting of Tory ministers on 16 October brimmed with unanimity on the question: a European alternative to Sikorsky, they agreed, should be put together, and the Government should do its best to encourage it. Heseltine was out of the country in early November, but when he returned he set his mind to the task. On 26 November, he met Sir John Cuckney, who from the outset was anxious to proceed with the Sikorsky take-over, and told him he was organising a European alternative. On 29 November, at a meeting organised by Peter Levene, the armaments directors responsible for government defence buying in four European countries – Britain, Germany, France and Italy – issued a unanimous recommendation: that all future helicopter production in European countries should be exclusively restricted to European firms.

Until this moment, there was no sign of the storm that was to come. Everyone expected that a European consortium would be formed, and an alternative scheme put to Westlands. Other things being equal, the Government supported Europe.

So Mr Heseltine was rather shocked when he found himself summoned to two ‘ad hoc’ informal meetings of top ministers on 5 and 6 December whose only purpose was to lift the recommendation of the national armaments directors the previous week. It was then that he noticed for the first time that his fellow ministers, not just Mr Brittan but the Prime Minister as well, were suddenly extremely keen on Sikorsky; and, as far as he could see, were out to ditch the European alternative which Mr Brittan himself had openly preferred. What had happened in the meantime? No one knew, or has ever known. The change had taken place, not in the Department of Trade and Industry, but in Ten Downing Street. At some time in the last week of November or the first week in December, something happened – perhaps in the course of one of those famous discussions on the ‘hot line’ to Ronald Reagan – which turned the Prime Minister from a neutral and rather bored observer of the argument into a passionate supporter of Sikorsky.

Poor Heseltine, who had never got on with Mrs Thatcher, found himself being treated rather roughly. At an Economic Committee meeting of the Cabinet, as he saw the Prime Minister and Sir John Cuckney taking the argument away from him, he begged for five days to ‘harden up’ the European proposal. ‘Give me till the 13th,’ he said (perhaps not realising that the 13th was a Friday), ‘and then let me come and argue it out with you again.’ He says another Cabinet Ministers’ meeting was fixed for the 13th at 3 p.m. – ‘when the Stock Exchange closed’. Mrs Thatcher said no such meeting was ever organised. At any rate, Heseltine busied himself all that week organising the European consortium.

He had a problem. Only one British company, British Aerospace, had joined up with other European companies in a rival consortium. What was needed was a bit more clout from a company not so easily identified with government orders. On 12 December, Mr Heseltine entertained a most important delegation in his office. It consisted of Sir Arnold Weinstock and Mr James Prior MP. The former was managing director and the latter chairman of the biggest manufacturing company in Britain, GEC.

Neither man was a favourite of the Prime Minister. The previous April, Weinstock had infuriated her with his evidence to the House of Lords Select Committee on British industry. He had ridiculed her claim that it didn’t matter so much if manufacturing industry declined, since the gap would be filled by service industry. If that sort of nonsense was pursued, Sir Arnold said, ‘Britain would become a little curiosity.’ Sir Arnold had long been sceptical of Mrs Thatcher’s Reaganomics. Like many industrialists, he was critical of the laissez-faire approach of the Government. Like the others, he was happy to keep his opposition quiet while Mrs Thatcher attacked and humiliated the unions. In the meanwhile, he provided a haven for Tory ministers who had left the Government in disgust. When Lord Carrington, the aristocratic Foreign Secretary in the first Thatcher Government, resigned over the Falklands, Weinstock took him in as chairman of GEC. Three years later Jim Prior, a consistent opponent of Thatcherite policies inside the Cabinet, decided he had had enough and resigned. Carrington stepped aside and Prior became chairman of GEC. Like so many other ‘wet’ challengers from the inside who had been cast aside by Thatcher – Mark Carlisle, Norman St John Stevas, Sir Ian Gilmour – Prior was not made of the stuff to fight the leader of his own party. A mild, bumbling man, he preferred not to step out of line. Michael Heseltine was different. Rich, abrasive and ambitious, Heseltine was fed up with Thatcher and her schoolmarm ways. In him, Weinstock, Prior and the ‘wet’ industrialists they represented saw a real champion, and even a possible Tory leader. They promised Heseltine their support, and before long were lining up their 1 per cent stake in Westland behind the European consortium, which they joined.

If he was pleased with his new allies, Heseltine was quite unprepared for what happened next. As he braced himself for the Cabinet meeting which would decide the issue on that Friday the 13th, he heard that it was not going to take place. When he protested, he heard to his surprise that it had never been arranged! When he said he’d been there when it was arranged, he was told he had been working all his five days under a misunderstanding. The matter was now left to the Westland Board, which, that same Friday the 13th, rejected the European alternative in about thirty-five minutes. When the European bid was improved on 20 December, it was still rejected. The Westland Board prepared to put only the Sikorsky offer to its shareholders. After Christmas and New Year, all sorts of strange things started to happen. When Heseltine went to argue the European case on the BBC’s World this Weekend on 5 January, he was surprised to hear that there had been a phone call from Downing Street telling the producers that the Minister of Defence did not have permission to take part in the broadcast (he took no notice). The following day, part of the text of a pompous letter from the Solicitor-General, Sir Patrick Mayhew, to Heseltine informing him that he had made a few trivial mistakes in a letter he had written on the Westlands business to Lloyds Bank, was mysteriously leaked to the newspapers. Two days later, on 8 January, Sir Raymond Lygo, chief executive of British Aerospace, the British ‘leader’ in the European consortium, was called to the Department of Trade and Industry, where he met a grim-faced Leon Brittan, his Minister of State, the ardent Thatcherite Geoffrey Pattie, and three top civil servants. When he heard what they said to him he asked in amazement: ‘Are you writing this down?’ After he left the meeting he hurried back to his own boardroom and told his astonished chairman and fellow directors that he had been told it was ‘not in the national interest’ for British Aerospace to continue in the European consortium, and that they should withdraw. Sir Austin Pierce, the austere chairman of British Aerospace, fired off an angry letter to the Prime Minister asking what was going on.

The following day, 9 January, Mr Heseltine arrived at the Cabinet meeting to be told that any future public comment by ministers on the Westlands affair was to be cleared first with the Cabinet Office. It was the last straw. He stormed out of the Cabinet meeting, and told a press conference he had resigned in order to argue for the European bid, and in protest at what he called a ‘grave breach of constitutional government’.

In the sensation which followed, the Government tried to explain it all away as a flamboyant gesture by a disloyal minister. But the more they tried to answer the charges of the outraged and media-happy Heseltine, the deeper they dug themselves into the mire.

On 13 January, in the afternoon (at 3.41), Mr Brittan was asked in the Commons about the letter from Sir Austin Pierce. He said he knew nothing of any such letter to anyone. Later in the evening (10.27), he was back again apologising to the House. There had been a letter, he agreed, but as it was confidential he’d thought it better not to mention it. What of the charge in the letter that the Government, while pretending to be neutral between the bids, had tried to pressurise British Aerospace into abandoning the European one? Well, Mr Brittan explained, his recollection of the meeting was quite different from Sir Raymond Lygo’s. He’d never asked British Aerospace to withdraw, and never said it wasn’t in the national interest for the company to take part in the consortium. From this blatant contradiction of Sir Raymond’s contemporaneous notes of the meeting, Mr Brittan was suddenly saved by a generous withdrawal from Sir Raymond, who accepted that there may have been a ‘misunderstanding’.

No sooner was Mr Brittan out of that, however, than he was entangled once again. The Prime Minister told the House on 14 January that she had set up an inquiry into the leaking of the Solicitor-General’s letter about Heseltine’s figures. On 23 January, she was telling the House that the leak had been authorised by Mr Brittan, with the consent of 10 Downing Street but without the consent or knowledge of the Solicitor-General. She found it all a matter for ‘regret’. A new debate was promised.

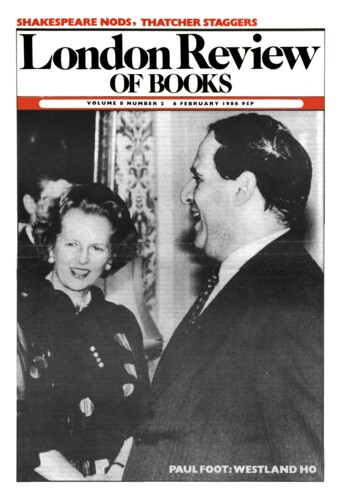

The Government’s apologists (led by the ultraright Minister of Transport Nicholas Ridley) try to pass off the whole affair as remote. Do the British public really care about a difficult argument between two rival capitalist bids? Do they care about what really was said between ministers and an aircraft industry boss in a room in Whitehall? Does it really matter who leaked what letter, when the information was all public knowledge anyway? The answers are all, probably, no. But those are not the real questions. What matters is that the central attractions of the Thatcher Government have been attacked at their roots. Where the Government claimed to be aloof and non-interventionist between rival firms, it has been exposed as shamelessly partisan. Where it persecuted others for leaking secret documents, it has cheerfully leaked its own secrets. Where it calls for others to return to Victorian values, it has been engaging in a street brawl. Above all, the Great White Rhino herself has taken a roll in the mud.

Send Letters To:

The Editor

London Review of Books,

28 Little Russell Street

London, WC1A 2HN

letters@lrb.co.uk

Please include name, address, and a telephone number.