Whether one regards the honours system as a comedy, or a scandal, or merely as a perfectly ordinary bit of government machinery – like other bits not always as sensibly managed as it might be – is a question about which it hardly seems necessary to get excited. The system can hardly avoid being all these things, and anyone who has watched its operations, even intermittently, over a number of years is likely to accept it more or less as he accepts the rest of our constitutional arrangements. Of course there are people – like Willie Hamilton – to whom the constitution itself is a scandal. Their disapproval of the honours system must be taken for granted. John Walker is presumably more open-minded, and willing to speak as he finds, though what exactly an enquirer finds must depend on his general perspectives. ‘This book started,’ we are told, ‘as an article for Labour Research.’ Walker spent five years in the Labour Research Department, which he has now left for work in local government, where, his publisher tells us, he is ‘25 years away from an MBE’. We wish him luck.

Although The Queen has been pleased is presented as a ‘detailed analysis of the Honours System’, it is much less thoroughgoing than such a title suggests. It contains a couple of dozen pages on ‘the first 500 years’, for our general education, followed by chapters on ‘Lloyd George’s maundy money’ and ‘the Wilson years’, and concludes with chapters – to which the whole survey may be said to be steered – on ‘Thatcher’s honoured industrialists’ and ‘Thatcher’s political honours’. It is nonsense to claim, as the publisher does, that Walker has conducted a ‘full investigation into the workings of the honours system’. The author himself tells us that when he first found matter for scandal in the Thatcher lists, he was ‘blissfully unaware’ of ‘any significant honours-for-sale practices in previous times’, which shows a certain ingenuousness, to say the least. There is a lack of knowledge of the world, too, in his assertion that the system ‘is treated with near reverence by all the characters who play a part’ in the sequence of recommendations – all, he says, except ‘some prime ministers’. It must be said that he tends to exaggerate the passion of potential recipients for the honours they might receive. People are pleased to have them, and why not? A few people get over-excited, but in most circles any undue hankering would be regarded as a psychological abnormality. The temperature throughout this book is a little too high. Walker appears to know nothing about the ordinary boring search for candidates which goes on all the time and results after all in some pleasure to the recipients themselves and helps to keep alive – against considerable odds, in a world like ours – the idea that there are forms of recognition other than money.

Walker hopes that the whole system will prove to be scandalous. ‘This book has looked only at the tip of the iceberg,’ he says in his ‘Epilogue’. ‘Who is to say that a similar story is not available to the assiduous researcher enquiring into the other 90 per cent or so who owe their rewards to the mysterious official machinery of the honours system?’ If it is excitement he is after, I am afraid he will be disappointed. The relatively modest crowd of worthies who are picked up by government departments are more likely to have been engaged in some boring but more or less useful public task than to have distinguished themselves by their skill in corruption. Walker’s fears go wider. He sees people of all kinds as being ‘controlled and kept in their place by the honours system’. There is something in this, of course – there is certainly comedy in it but whether the control is so powerful, or the place so publicly useless, as to render the system deleterious is a matter which would need far more patient and less partisan enquiry than Walker gives it here, before one could conclude that it should be abolished. What appals him particularly is that ‘the honours system is a mirror of a class-conscious society ... No man (or woman) must be allowed to rise above his or her station – the gong depends not on the goodness of the deed, but on your position in society ... it would never do, would it,’ he asks with heavy irony, ‘for a head of the Home Civil Service to receive an MBE when a clerk in a Social Security office in Newcastle received a peerage?’ Well it wouldn’t, really. Even the head of the Civil Service would not receive his peerage till he retired, when his counsel round about the House of Lords might or might not be useful; if a clerk in a Newcastle office were to receive one, it could only be concluded that he had powerful political friends. A clerk who became a Permanent Secretary – which has happened – would get his KCB. The ordinary awards in the various orders of knighthood are given in a context, and those concerned, either as recipients, or as people who ordinarily have to do with such characters, know very much what to make of them. The notion of an award for virtue, which seems to be at the back of Walker’s criticism, is absurd.

One could well imagine doing without an honours system. Schopenhauer, who had a gift for the wounding phrase and liked to show his contempt for the world at large, said that he found it altogether suitable that there should be ‘crosses and stars’ to declare to the undeserving majority: ‘The man is not like you: he has merits!’ He added, very properly, that a prince should be careful how he distributed his insignia: if the distribution was unjust, or ill-advised, or merely too free, they would lose their value. Schopenhauer’s arrogance is as excessive, for the real world, as Walker’s moral indignation. In a more practical vein, Schopenhauer suggested that the state could save some money by paying people partly in honours. Everything depends on how people take these things – not only the recipients but the country at large. So far as there is a public opinion on such matters, it may be said to have swung heavily in Walker’s direction since Schopenhauer’s day, but it would be rash to presume too far on this. The public reaction to Wilson’s reckless resignation list of 1976 suggests that he carried his rather grand seigneur irresponsibility a bit too far for ordinary democratic taste, and it may be that Walker himself is a little light-headed in his praise of the ‘reforms’ alleged to have been carried out in the earlier Wilson years. The trouble is that he sees honours not as a working system but as something for the media and for those who soak up the media’s productions most uncritically. His contempt for the ‘tedious list of worthies’ of no general interest is surely out of place: at any rate it would need a much closer examination than he gives it before one could conclude that it does nothing for the performance of the many unspectacular tasks which have to be done by somebody. On the other hand, peppering the list with ‘stars of stage and screen’, sportsmen and such as ‘the punter’s pal’ does nothing for the machinery of state and could surely easily be overdone. Walker himself gives what was no doubt the real reason for Wilson’s rather heavy emphasis in this direction. ‘Harold Wilson,’ he says, ‘knew his public and electorate, particularly the Labour voters’ – ‘the honours lists were yet another medium for establishing his man-of-the-people appeal.’

There is surely a case for looking with suspicion on all honours which serve party rather than national objectives? But the question should not be taken to imply that honours to public servants cannot be overdone, only that the scrutiny of them should have national and not party interests in mind. There is certainly comedy in the case of the Foreign Office man who complained in the Times that he was ‘the first of HM’s former ministers to the Holy See over the past 60 years not to be knighted’. ‘Poor “Sir” Desmond,’ says Walker, ‘he is still unadorned and so must content himself with his Coronation Medal (1953), CVO (1961), CMG (1964) and Knight Grand Cross, Order of St Gregory the Great (1973)’ – this last, evidently, a foreign honour. The case must be exceptional, the retired official concerned particularly silly, but the size even of the reduced Diplomatic list looks to an outsider rather more impressive than it need be. But such questions are only a part, and a minor part, of considerations about the function of the Foreign Office in general. ‘The mass media must have “names” to write and broadcast about, otherwise the lists would not receive the attention that the patronage machine requires them to get.’ So Walker, thinking as usual about the great pseudo-public world of the media rather than of the multifarious and on the whole unobtrusive world in which work is actually done. The predominance of the media in our world must no doubt affect the honours system as it does everything else, but plenty of willing and well-paid hands are speeding that process. The trouble about the media is that they deal mainly in gross oversimplifications which have a ready entertainment value, and the actual business of the world requires a different approach.

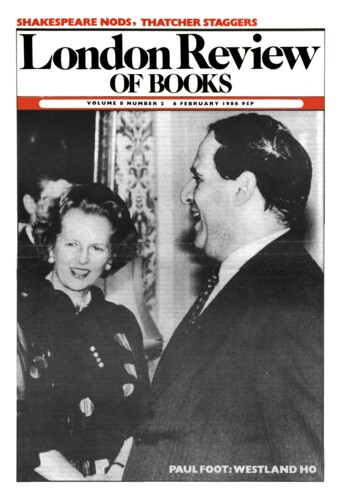

It is – naturally enough, in view of his frankly partisan approach – in the chapters on the Thatcher Government that Walker pays most attention to the question of party bias in the distribution of honours. With our party system of government, something of this sort is normal and in itself surely not improper, since the party in power is the one which, by definition, represents the temper of the country at the time – with all the reservations which can be made about that. At any rate, others have only to win an election to have their turn. It still remains the case that a party is only a party, and a great deal of discretion is called for in the face of a public which, mercifully, is never anything like unanimous. Put another – and, I suppose, less fashionable – way, the government is the Queen’s government and the only one any of us has; it is not Mrs Thatcher’s or the former Mr Wilson’s, except in trust for all, present and future. The working of the honours system ought to show a consciousness of this on the part of those who direct it, and in a numerically large part of the list it always does, as when an MBE alights on some locally known, but otherwise obscure, voluntary worker, somewhere far from Westminster. It is in the more heady part of the list that the danger arises, and certainly all that Walker reports on this subject deserves careful consideration, some of it from rather wider points of view than his. What really accounts for the light in his eye is the fact that ‘the companies of the industrialists honoured by Mrs Thatcher have accounted for 43 per cent of the corporate donations Labour Research has traced as going to the Conservative cause.’ He hopes that this constitutes the sale of honours and that it is a scandal. No doubt lawyers will advise on the relevance of the Honours (Prevention of Abuses) Act, 1925: meanwhile one must say that if the purchase of an honour was what the industrialists in question had most in mind when the donations were made they would hardly be the ‘very successful and distinguished businessmen’ Walker describes the industrialist peers created since 1979 as being. The question where political parties get funds from is a matter of legitimate public interest, which goes far wider than any connections, real or suspected, with the Honours List, and it cannot be said that any party has solved it in an entirely satisfactory way. Does a party represent an interest or a wobbling mass of opinion? There are those who regard the latter as more respectable, but the element of interest is what provides the drive and the stability. Neither the trade unions nor industrial and commercial enterprises satisfactorily represent what the two dominant parties speak for, but who else is likely to put up money, in sufficient quantities?

No one really supposes that the industrialist, trade-union leader or academic who becomes a Life Peer is suddenly vested with feudal prestige, nor that a knight is authorised by his title to play the squire. Walker appears to be jealous of the dizzy heights on which such people walk. Need he be? Admittedly the system is not wholly serious: thank God it is only one of the many ways in which people can be comforted by a little feeling of superiority. Think how terrible an infallible system would be, and how we should have to respect those decorated by it.

Send Letters To:

The Editor

London Review of Books,

28 Little Russell Street

London, WC1A 2HN

letters@lrb.co.uk

Please include name, address, and a telephone number.