Rolling Home

for Tony, former student

In that shop the things

stuck out their mitts

wanting to strike bargains,

get on with the job.

Hammers, brace-and-bits,

hearty saws, planes that I’m

cackhanded with,

chisels with more edge

than I can trust,

that scoff at fumbling,

my kind of muscle.

‘Get yourself a big one, dad!’

Your joke was good, went home:

I could have had a son your age,

been less tentative with things,

had muscle in good stead.

Later

in the glibnesses of whisky we

went staggering back through talk

of loves mistimed, ill-judged,

betrayed, unpicked our histories,

the same backslidings, prodigalities,

made trial of honesties, accused

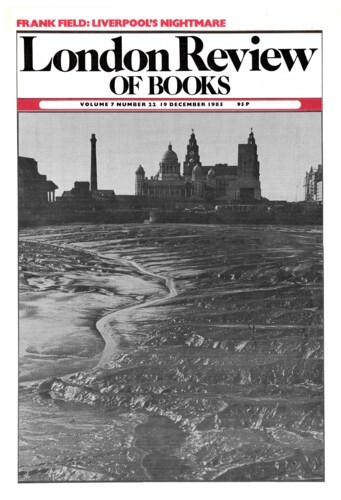

this hard-faced Liverpool

which gave us all our cockiness

and guilt.

Through my window, surprised

to see it there – Ford’s Assembly Plant,

dreadnought on the riverbank too gross

to launch – you said,

‘My father’s working there ...

this exact moment ... while we booze.’

Something trembled, tautened.

‘You’d like my dad,’ you said.

‘See you on the Christmas tree,’ she said

OK, dear aunt, I will look out

for you among the evergreen,

know you by – what else? –

that squeezebox laughter which

wants us never to grow old.

Just give me time

to rub the glitter from my eyes.

No cause to miss the divilment,

my dad’s old buck in me. I’ll act

the goat for you – that’s if

for some daft reason

he’s not there – and we will jig

the hornpipes he was famous for.

Shameless, cuddling me, you’ll say

‘They got fed up of me,

they threw me off the oilrigs, Matt.’

And we’ll guffaw for years and years.

And he’ll be there, your Ernie, too,

tuned in to Billy Cotton’s Band.

And then when it’s two o’clock he’ll wink

and nudge you up the wooden hill

to do what you did on Sunday afternoons

and I’ll let on you’re dozing off

plum duff.

And I bet I click

with the blond goodlooker

on tiptoe there at the top of the tree,

the one with the flimsy tutu

and magic on her hands.

Coughing

We were on about miladdo

coughing at the bar and tugboats.

I somehow got it in my skull

that you were twitting someone here.

Tendons tautened, memories nudged.

Something needed sticking up for,

wanted praise.

Like what? I said,

an old tugboat? Yes, but solid muscle,

all heart, shaped to strain, to heave

and lug, to see great liners off.

Marvelled at Simmo, remember?

All that dying in a fierce room

bulked about with wardrobes; how

we whispered that his heart

was workhorse, how we knew

he’d let no mercy in, would have

no pity on himself.

I thought

of block-and-tackle jobs,

white hoisted sail, canvas with

a bellyful of speed.

Mrs Clancy

wasn’t tense and willowy

fussing the Nature Table’s twigs

like tall Mrs Fairclough,

or tweedy-posh like kind

Miss Bingham with

her copperplate and poetry,

or young and rashly lipsticked

like pretty Miss Taylor

biking homewards over cobbles

to toughen up her tennis thighs:

she was hard as ground

ice grabs hold of,

using the streets’ snide

and whinge against us,

mimicking mother’s tongue

or father’s fist,

making small hands scat

like rabbits over desks,

rapping knuckles with

the rat-bite of her twelve-inch rule.

Send Letters To:

The Editor

London Review of Books,

28 Little Russell Street

London, WC1A 2HN

letters@lrb.co.uk

Please include name, address, and a telephone number.