Each morning when shaving I look at my reflection and a small and depressingly accurate mirror presents me with an image from which I have never derived any satisfaction. That is not to say that I am disappointed. I have never expected anything. If I were asked to write a short essay describing my face, the description would be unrecognisable to anyone who knew me well. I will not distress myself by offering descriptions of individual items of the entire contour. I well recollect on one occasion, after giving a lecture, seeing a report of it from a young woman which said that ‘the lecturer (a singularly ugly man) came into the room’ – but then I must with vanity add her further words: ‘and with a few well chosen sentences induced oblivion about his appearance that remained until the lecture ended and thereafter was immediately restored.’ I have any number of vanities. In the whole of this diary, in the whole of this issue, it would be impossible to compress the catalogue. I shall not gratify my enemies with this material, but it does enable me to say that common sense has always precluded personal vanity as one of my weaknesses.

This brief introduction enables me to inquire why it is – having regard to my appearance, and having regard also to my belief that a combination of El Greco, Titian, Rubens, Rembrandt, Van Dyke and Renoir would not convert me into a beautiful object or, more importantly, an object of aesthetic interest – I have so often been pursued by artists, and artists of great quality, who wished to do a portrait of me. There is, of course, a singularly unflattering explanation: that given the choice between painting Prospero and Caliban, the latter might very easily receive the majority vote. But modest as I am, I do not believe that is the explanation. Caliban had attributes that I do not claim to possess, and anyone painting him would be painting him with those special qualities. Prospero would of course be a dull fellow to paint and in the silence of the night I admit to myself that I am not a particularly dull fellow.

The reader may ask why, holding these views about my appearance, and the belief that no reproduction is likely to bring great joy to the viewer, I should have succumbed relatively often to the request to be ‘done’. The explanation here is simple. A willingness to be painted does not arise from vanity or a belief that there is something lovely to be presented to mankind, but rather from the belief that the petitioner sees something in you that you do not see in yourself, and time and again I have the mortification of seeing how totally true this is. But there is another reason too. I now know that my response to a request is largely determined by the simple human vanity of supposing that if the artist asking is eminent enough and distinguished enough I should derive a certain amount of innocent pleasure from the knowledge that most of my friends have only contrived to be asked by lesser artists. I do not think this is a particularly ignoble sentiment. It demonstrates a willingness to do honour where honour is earned.

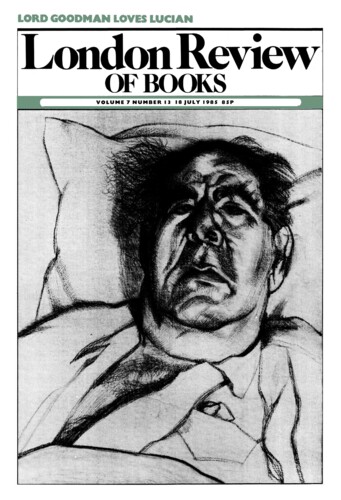

Which brings me to the reason why I was asked to write this piece: that a very great artist – who has now in a sensationally short space of time become a very close friend – unexpectedly asked if I would like to be drawn by him. I refer, of course, to Lucian Freud, the product of whose activity is to be seen on the cover of the London Review of Books. I do not think I hesitated for a moment when he asked me. I was flattered beyond words, and a more cautious and vainer man would have stopped to reflect about how Goodman drawn by Freud was likely to appear. But the mere privilege of Goodman being drawn by Freud was enough for me.

Describing the process of being drawn by Lucian Freud, or indeed the process of any human relationship with Lucian Freud, is, I suspect, beyond my literary skills. Leaving aside his talent as an artist, which has been sufficiently lauded in much better-informed quarters, he is indeed one of the most remarkable people I know. Remarkable in character, remarkable in habits, remarkable in personal relationships, but perhaps most remarkable of all in diet. The drawing process consisted of Lucian arriving at my home at what for me was the middle of the night, usually about 8.30 a.m. My bleary-eyed housekeeper would admit him, and the difficulties associated with bathing, shaving and dressing at that hour were summarily solved by a decision that he would draw me in bed in my pyjamas, unshaved and unbathed, before a single brush or lotion had been applied to the untouched exterior.

He chose a position which for the initial drawing – he is now at work on a second – was not entirely comfortable. I was lowish in the bed, with inadequate support for my head, and I frequently arose with a rick in my neck. But he displayed exemplary courtesy in inquiring whether I was comfortable, periodically prodding the pillows, so that there was some slight mitigation of the agony of the position, and I responded with equal courtesy by refraining from any complaint of any kind, however tortured my position. Moreover, in a very short space of time we were engaged in conversation that distracted one from physical miseries.

I would start by inquiring whether he had had breakfast, to which he replied that except at certain times of the year he did not eat breakfast. The times of the year when he ate breakfast were – and I could give my readers a thousand guesses – when woodcock were available. The notion of Lucian devouring a woodcock in the early hours of the morning left me with a faint nausea, but I discovered that although he had not breakfasted when he arrived and would only occasionally take a cup of tea or coffee at home, he would then depart to eat a substantial mid-morning meal with his elder brother, who carried on an interesting business in the vicinity, when they would proceed together to a local French patisserie and drink coffee and eat brioches and pastries to fill what by then must have been an enormous gap.

The conversation, however, was not by any means restricted to gluttony. My breakfast days are now, alas, sad and historic memories. There was a time not so long ago when, having consumed some grapefruit and possibly some cornflakes, I would get down to the serious business of egg, bacon, sausage, fried bread, a stack of toast and a full complement of Frank Cooper’s darkest Oxford marmalade. But one morning the mirror vision disclosed an expansion to such an extent that the full image could no longer be portrayed within a single mirror. The shock was serious and the reaction immediate. From then onwards I have had a large glass of Complan – which I strongly recommend as providing sustenance without excessive substance – and an apple or a small bunch of grapes, topped off, if I have time, with a cup of coffee.

And from food we proceeded to conversations as stimulating as I have known for many years. I have a wholly amateur and very unacademic knowledge of art and artists, but sufficient to enable me to listen to the voice of a master. Lucian’s knowledge of the artists of all generations is prodigious and encyclopaedic. He would delight me with quotations from what Rembrandt had said or Van Dyke had said or Whistler had said. It required no effort on his part to dip down into this immense fund of artistic anecdotage to provide some immensely appropriate comment on whatever it was we were talking about.

Other artists who have painted me – and in at least two cases they have been artists of recognised quality and indeed in one case of world fame – did not provide the conversational delights that anyone who is intimate with Lucian could enjoy if they had the good fortune to be his model. That is not to say that I have not enjoyed conversations with artists and found a number of them to be conversationalists of good quality, but the razor-sharp objectivity of Lucian’s comments – his surprising, and I hope he will forgive me if I say unexpected, generosity towards all his contemporaries – revealed a mind that set artistic truth high above local gossip. That is not to say that he was slow to condemn as worthless an artist whom he regarded as worthless, but he did so in terms that made it clear that this was an aesthetic judgment and not a professional jealousy. He praised artists for whom I had little regard, and was highly critical of artists whom I admired and I regret to say continue to admire despite his strictures.

Except during the odd moment when I fell asleep and would be woken by a tugging at the pillow, I can think of no period when we were talking together which was dull or tedious or free from entertainment. What made the range and attraction of our conversation so surprising to me was the width of his interests in so many fields outside of art and painting. It is well-known that he has an obsession with horses, but it would require an article in itself and a far more practised psychoanalyst than myself to identify what particular motivation causes him to enjoy the loss of his money. He derives a mild satisfaction from winning but an absolutely perverse delight from losing. He appears at the moment to have assigned me as his time-off model when he has nothing else to draw. Hence on departing, usually around 11 in the morning, he will make arrangements to come back in the next two or three days, but feels not the slightest resentment if I ring before then to explain that some engagement has intervened, whereupon a fresh appointment is made.

Since I make no claim to be able to describe the artist’s technique, the reason for his choice of crayon or pencil, of one particular sharpener over some other, or the shape and dimensions of his easel, I will leave such references to the Lawrence Gowings of this world. And I will conclude by saying this: that it has been a rare privilege to be drawn by Lucian because it has been an undiluted pleasure. He is one of the most exciting human-beings I know. There is not a day when some element of novelty does not emerge from his conversation, and I always see him depart with regret, coupled with some feeling of dread that misadventure may befall his antique motor-car – the love of his life.

Send Letters To:

The Editor

London Review of Books,

28 Little Russell Street

London, WC1A 2HN

letters@lrb.co.uk

Please include name, address, and a telephone number.