In the darkness a faint spot of light appeared, pale yellow, the reflection of a star untouched by cloud. It blinked out for a few seconds, then reappeared, moving up and down, intermittently hidden behind branches heavy with leaves. Kneeling on the arm of a chair in the darkened study lined with books – smelling of books – he watched the light greedily, his nose pressed against the window, his breath misting the glass.

‘Dive right to the bottom of the pool!’

The sun skittered over the choppy surface, a few cold drops of water brushed his legs and melted on his smooth skin. He heard a bell in the distance chime once, fading to a brief, resonant hum. His toes curled over the edge as he hesitated.

‘Right to the bottom!’

– He’s just a kid, I don’t have to listen to him. ‘Come on then!’

– Eddie says it too, though. He’s a good swimmer.

Still he hesitated, watching the jewels dance, unsure, as if it was a much greater thing he was afraid to commit himself to.

– They’ll splash me in a minute, I’ll dive down deep, deep to the bottom, now, it looks lovely even though it’ll be

Cold! a shock thrilled through him as he hit the water and very suddenly he was in a different body, a less clumsy body, wading downwards. He paused and rolled over and his eyes ached at the light as he squinted. Disorientated, he watched the branches of a tree wave and blur above or below like a thin cloud.

– Right to the bottom.

On the floor of the pool, to his surprise, there was a greenish film, like mould or the mark of a disease. A fingernail whirled it into a tiny mist, dust caught in a shaft of sun.

– Breathe, I want the surface, it’s cold.

He churned upwards, seeming to grope for invisible hand-holds, and as he broke the surface Eddie splashed him full in the face. In return he ducked him while Jenny and Charlie. Eddie’s younger brother and sister, splashed him ineffectually. They played an energetic kind of water polo which seemed to involve him and Eddie throwing the ball back and forth over the heads of the two younger ones.

I knew Eddie for four years, until we were nine and his parents took him out of our school after only one year and sent him to a boarding-school somewhere. The year before that they had a pool put in their garden and I still remember the first months of that summer as an idyllic time spent in and around that pool. The water and the sun, and the big green garden, colour the memory of these months and to think back is disorientating, like trying to imagine myself in a different body.

The ball bounced out of the pool and he pulled himself out after it, water streaming off his body. He ran over the paving and onto the lawn, shivering in the warm sun he picked up the ball and ran back with it.

‘Clean the grass off your feet first!’

– Who? Oh! Quickly, it’s cold.

It was Eddie’s mother, Mrs Fox, calling from the house. He sat by the pool and threw the ball in as he wiped the soles of his feet, transferring the soggy grass to his palms and then brushing and clapping it off.

‘That had grass on it too.’

– The ball? No it didn’t, I didn’t see any.

Eddie threw it back. ‘Better clean it.’

He peeled a blade of grass off the ball, looked towards the house where he saw Eddie’s mother coming out, and jumped in with it.

– Never get warm again now. Why are you watching like that? Don’t watch.

The game continued, a little subdued under the eyes of Mrs Fox. She was sitting in a comfortable swinging seat beneath a canopy, its bright floral print matched her dress. There weren’t any flowers in the garden, only grass and paving and a beautiful weeping willow. It was planted well away from the pool because its roots would be attracted to the water. He used to imagine them uneasily, they would be crawling like stubborn blind earthworms beneath the grass.

Now and then Mrs Fox would heartily urge Jenny and Charlie to try harder. She suggested a change in the teams to make it fairer but Eddie didn’t hear, or perhaps he ignored her. Once the ball was thrown out near her feet, but she made no move to kick it back into the water and Eddie fetched it from beneath the seat, not looking at her.

They got out after a while and the four of them jogged up and down on the grass. Eddie stopped jogging on the spot and began to run round the lawn, Charlie followed him and soon all four were running round and round in the sun.

‘I can run fastest!’ shouted Eddie.

‘No you can’t!’

– Faster, sun and wind, wind and sun, faster, I can run fastest, faster.

Sun and wind seemed to cleanse him, as if he were shedding a skin. ‘Blow dry!’ Jenny shouted, ‘We’re having a blow dry!’ They ran on, shouting and laughing, in a ragged circle, as if in some wild tribal ceremony that might never end – he thought they might never stop.

I like to remember that scene, it makes me smile. I know that to idealise the past is absurd, even the sun-drenched early part of that summer probably wasn’t carefree; it’s just nice to think of it that way. It gives me a vague sense of something lost – that old cliché.

Jenny and Charlie were already flagging when Charlie suddenly let out a howl much louder and more piercing than the other shouts. He fell to the ground crying.

His mother watched dispassionately for a moment as he clutched his foot and howled, before she called out, in a tone more weary than concerned. ‘What is it? Stop crying and come and tell me what’s wrong. Come on then.’

– What’s wrong with him, what with her? Why doesn’t she do something?

Charlie didn’t move, howling all the louder. ‘Come on then.’ Her tone didn’t change and she remained on the seat, watched by the other three. The pause seemed to him to last for minutes.

At last Charlie got up and half ran, half hopped to his mother. He had been stung.

‘That’ll teach you not to step on bees, won’t it?’ said his mother.

Charlie’s red face was contorted in surprise and pain, he was four I think, or five, but she told him not to be a baby as she pulled out the sting with her long finger-nails and he let out another howl.

– Euggh, glad it wasn’t me. Look out though, they’re in the grass, be careful.

They tiptoed with elaborate caution back onto the paving around the pool. Charlie’s crying gradually became forced, with long drawn-out sniffs intended to show he still required attention.

‘Why don’t you all get dressed,’ said Eddie’s mother, walking back to the house, ‘and come inside and I’ll make you some tea.’

He watched her sandals slapping the paving beneath her thick ankles.

– Go away. Yes I’m glad you’ve gone, you don’t like me. You don’t even like Eddie!

He shifted uneasily at the thought. ‘Bum print!’ shouted Eddie, pointing and laughing hilariously. They began to move around the side of the pool, around the quiet water, raising and lowering their bottoms, leaving increasingly faint damp patches with their swimming-trunks. Jenny, who was six, thought the game was great fun. ‘Mine’s better’n yours, you can’t see yours.’ She sat up and down happily.

After watching for a while Charlie decided to overcome his pain and join in. When he was near the side at the shallow end, Eddie stretched out an arm and pushed him in roughly. ‘Cry baby,’ he sneered. There was more shouting and threatened tears as Charlie flailed in the water, but Eddie ignored him, leaving Jenny to help him out of the pool. It was hard to tell now if he had cried, his face soaked, his eyes reddened by chlorine.

Inside there were sausages, cole slaw, lemonade, and Charlie forgot his grievance. There was silence for a few minutes while they ate greedily, satisfying their appetites. ‘I’m going to be on the swimming team,’ said Eddie, his mouth full. ‘If you don’t just use the pool for throwing a football around,’ his mother looked up from the stove.

‘Me too.’ said Charlie.

‘You’re not even at school.’ His sister was scornful.

‘What about you, you’re very quiet aren’t you? Are you shy or just thinking?’

‘I don’t know.’ He glanced at her, then looked away.

– Not quiet, not shy, just thinking. What’s wrong with thinking? What’s wrong with playing in the pool? That’s what I’d do if I had one, but you make him practise all the time, try to make him anyway.

The food was good, it always was in Eddie’s house. It was an expensive kitchen, solidly furnished in wood with an Aga stove. Before they had finished tea he heard the front door open and a few minutes later Eddie’s father walked in, tall, dark-suited, silver-haired; home early from the office on a hot summer friday.

– Why’re you here? I’ll go soon, he’s not nice to anyone.

He kissed his wife and hugged her, then he looked down at the table. For a smile, one side of his mouth pulled sideways a little. ‘Look we’re embarrassing him, isn’t that sweet.’

– Shut up! I’m not embarrassed, why did you have to say that? He’s not nice to anyone.

‘Aah, he’s blushing.’

He was a frightening man then, easy for an eight-year-old to dislike. His snide comments made no allowances for children, he’d laugh at them or be easily irritated by them, but he couldn’t even pretend to be friendly with them.

The boys soon escaped to Eddie’s room to play a board game. It was a small room, cluttered but comfortable. There was a bean-bag which he coveted and an old record-player with one record, ‘The Jungle Book’. Around the room were little soldiers in menacing positions, a couple more games, a dartboard, another football in a corner. Eddie had a five gear bike too.

– I like it here, all the house is nice, especially the pool, why can’t we have a pool, but my mum and dad are nicer than yours why can’t we have a pool and me have a bike but not ...

‘It’s your turn. You’re not looking.’

‘All right.’ He threw the dice and looked at the board: ‘Wait a minute, you didn’t say you were there, you owe me eighteen pounds.’

‘No I don’t, you threw the dice.’

‘I said it first.’

‘You didn’t.’

‘Yes I did.’

The game ended and the argument ended too, before it got serious enough to carry beyond the game. He had moved to the window. ‘There’s my house! Through the trees, look that’s our red roof.’

‘It doesn’t look very far.’

‘That’s because we’re looking over all the gardens and stuff. You have to walk all over the place, round corners.’

‘It looks closer at night.’

– My house. It looks like all the others but I bet they’re all different inside. What is inside them all under the roofs? Which room can I see? My room’s not as nice as this one, why can’t I have a bean-bag?

‘I bet people think it’s spies with secret messages,’ said Eddie. ‘We should have a code. No one must know, especially my father.’ He paused and his face changed. ‘I hate my father.’ He said it casually, not for effect, not even expecting any reaction.

– You can’t hate him, not your father, I can hate him you can’t.

‘You don’t really.’

‘I do. I hate him.’

When it was time for him to go, they found Eddie’s parents in the kitchen, they were talking and he waited for them to finish, not sure how to interrupt.

Mrs Fox saw him, ‘Off are you?’

‘Thank you for having me.’

‘Isn’t he polite?’ said Mr Fox.

He backed out of the kitchen, said goodbye to Eddie and left. Once out of the house he ran for a bit along the busy road, though he was in no hurry. It was getting dark.

– Polite! I wasn’t even talking to you. He’s horrible. Embarrassing me, maybe I was embarrassed, but so what – he didn’t have to say anything. Wish we had a pool, though, and a bean-bag and a big five-gear bike and a record-player and a pool and a pool ...

His thoughts fell into the rhythm of his running feet until he slowed down to a walk, panting. He stopped for a minute and looked up at the still faint sliver of the moon, like a finger-nail scratch on the sky. It didn’t look very confident and at the edge of the sky between silhouettes of houses he could see there was still pink interference from the sun. It reassured him to see these things, it always did. He began to run again, more calmly.

– What time? Lots of time left, lots and lots, where’s the torch though, where did I leave it, I’ll have to find it, glad I’m not Eddie, good idea though, his idea, where’s the torch, wish I had a pool, had his bike, glad I’m not him, glad I’m not him ...

At nine o’clock, as his parents started to watch the News, he ran up the stairs and into the study, his parents’ room where he wasn’t usually supposed to go. He thought of it as a small library, he had never seen so many books outside a library, it was where they worked or planned whatever they did that bought the house and the car and the meals. So it was a very special place, appropriate for Eddie’s idea. He sat in the window and looked out into the night. Heavy cloud approached the moon now, threatening to knock it from where it hung, down to the puffy trees below. He flicked on his torch and the beam disappeared into the night.

– How can he see it? It’s too small, he won’t see it. Dark in here, where is he, has he forgotten? Dark.

Across the night a light appeared, swayed from side to side a few times and flicked off again. He grinned and waved his own torch up and down, described a careful circle with its beam.

– Hello, I can see you, I can see you, in the dark in your room with the soldiers, I can see you.

The novelty was still there, seeming to suggest exciting possibilities. The simple fact of two boys signalling to each other with torches over a short distance wasn’t enough, it had to be elaborated. It was a starting-point, a place to begin, and that night in bed his imagination took over, creating a secret club with its own special means of communication, an endless network of feeble lights over a vast area, a dim reflection of the night sky. Secret from all but the elect.

– Don’t let them know, don’t think about them, not here in the dark where it’s peaceful and comfortable and dark and warm. It’s too good to think about them here. Here, floating. Here flying. Flying on the bed I can make it rise like a carpet, an aeroplane. This button makes it rise, this one opens the windows, opens them wide open so the bed fits through and this one makes it go through, into the sky. My eyes are closed is why I can’t see it but it’s really happening, there’s a force-field stopping the wind is why I can’t feel it but it’s really happening. It’s really happening. My own secret. I can fly.

In the background was the noise of traffic but it didn’t interrupt, it was comforting. It told him that others were awake, that it didn’t matter if he didn’t sleep all night long.

– I could fly to Eddie’s window, better than a torch. Or to Paris and the top of the Eiffel Tower and look at the city. But I’ll go into space, all alone, the force-field will keep the air in and it doesn’t matter if I stay out all night. I’ll go and look at the sun and the stars.

The idea was a place to begin. And even in the silence of space, even in the quiet of sleep, the sound of traffic whispered in the background.

The next day was saturday and they met again at Eddie’s house, spent a morning that mirrored all the mornings and afternoons of the summer until then. They swam, sun-bathed, talked about signals with torches, tacitly tried to avoid Eddie’s father.

At lunch-time he ambushed them. He came out of the house with a sandwich, some beer and a newspaper and sat in the swinging seat, a presence that could not be ignored.

‘Don’t stop talking on my account.’ He took a bite of the sandwich and spoke with his mouth full. ‘What were you talking about?’

‘Nothing.’

‘What were you talking about?’

Eddie was silent, gazing into the pool.

‘Tell me what you were talking about.’

– It’s a secret, don’t tell him, make it up.

He squirmed at the tension between the father and the son.

‘Torches,’ said Eddie finally. ‘We made signals between the houses with torches.’

‘What did you do that for?’ The question had no answer. ‘Well, why did you do that?’

– What does that mean, why? We wanted to is all and why not? Why did you tell him, why is he like that? Let’s go away.

‘We could see the light through the trees,’ said Eddie.

‘That doesn’t answer my question, does it?’

The bright sun behind Eddie’s father dazzled them, nothing seemed to be visible except that insistent smile, the mouth pulled slightly to one side. ‘It was fun.’ said Eddie sullenly, looking up at his father, just for a moment, with narrowed eyes, forced to expose and demean whatever they had both felt.

‘I hope you put the torch back where you found it,’ said his father, and went back to his newspaper.

Around the corner from Eddie’s house was a patch of land called the allotments, long overgrown and due to be built on. Surrounded on three sides by rows of houses, it was edged along the road by an old wooden fence with a gate that was always open. It was dotted by bushes, there were uneven slopes and dips, some rusty old rubbish in one corner might have been the skeleton of a car.

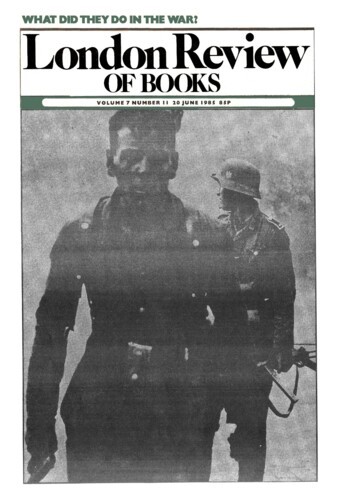

People came there on scrambling motorbikes and kids came on push-bikes and played epic games of hide and seek or chain-he, but its special fascination was a bunker, built in fear of invasion during the war, squatting in the middle of the land. It was thick, dark concrete, pock-marked now, a hexagon, or perhaps an octagon, with two small, square windows. Inside, a broad, angular column left room for only one person to walk around it comfortably. Fading graffiti covered it like a pale, ugly fungus and it was used regularly as a toilet. It sat on the green hillocky land like a stinking, black tumour, like mould on the floor of a sparkling swimming-pool.

It was here that the boys came. A shaft of sunlight through a window illuminated some kind of slime on the face of the interior column. It was as if it had been stuck there, trapped, preventing the light from moving so that the shaft was a giant lever stretching into the sky.

They pulled themselves up onto the low roof, bathing in the still-hot sun.

– Bet this has been here for ever. For years and years, since the war. I’d never have surrendered if I’d been here, I would have stayed for ever, thick walls, safe and dark.

He imagined war as a young boy does, his mind on Eddie’s soldiers – people standing a hundred yards apart, hidden behind cover, shooting at each other with rifles. An exciting occupation, without complications or shades of emotion, a simple war.

‘Never mind,’ he said, ‘he doesn’t matter. We can still do it.’

‘We can still do it.’ Eddie nodded.

There was a pause and they heard the church bell chime again and a car passing. Low, brief sounds, quickly fading in the still air over the quiet ground.

‘Your dad, he doesn’t matter. He doesn’t understand.’

‘I’m going to kill my father,’ said Eddie, in the same matter-of-fact tone he had used to say he hated him. His finger-nails scratched at the hard, stubbly concrete as if he was trying to dig beneath it.

The quiet was suddenly interrupted by the jarring sneer of light, low-powered motorbikes, a comment, it seemed, on his words. The riders’ excited shouts mingled with the sounds of their bikes, they were like children showing off to each other and to themselves. After watching them for a while, lying on the roof in the sun, they went back to Eddie’s house, their mood no better than when they had left. The light was already fading, the lever perhaps had affected the sun.

Eddie sat in the bean-bag, eyes on the ceiling, rolling the polystyrene beneath the cover between his fingers. He sat up abruptly, as if he had been dozing. ‘Let’s go garden snooping.’

‘What’s that?’

There was a knock at the door and Jenny came timidly in, followed by Charlie.

‘I’m bored,’ he announced, before Jenny could say anything.

‘So what?’ said Eddie, ‘Go away.’

‘We’re bored.’ Jenny insisted. ‘We want to do something with you two.’

‘Well we don’t.’

‘Mummy said to ask you,’ said Charlie triumphantly.

‘Get lost.’

‘I’m telling,’ he said and ran out, followed by a more dignified Jenny.

‘Bloody kids,’ said Eddie.

– Bloody kids, bloody parents, bloody Eddie, bored. I don’t like this house any more, house ...

‘What’s garden snooping?’

‘Alan told me at school, he goes at night into people’s gardens and creeps around them like soldiers.’ Eddie was suddenly enthusiastic again.

‘I don’t want to, I don’t like him, I bet it’s not true.’

‘There’s a house on Park Road where no one lives, but it’s all done really modern and nice. It’s to show people what all the other houses will look like when they build them. We can go there because no one lives there so it’s safe.’

– I can see what’s inside. Must be nicer than here now. Like soldiers.

‘Come on, we might as well, no one will see us.’ Eddie’s eagerness was intense and persuasive.

The door opened without warning and his mother walked in. ‘Why are you two sitting in here in the dark? It’s summer, there’s no excuse for being bored.’

‘Eddie and me are going for a walk.’

‘Eddie and I. Well take Jenny and Charlie with you.’ She raised a hand towards Eddie. ‘Don’t argue with me, I warn you.’

– I’m going and I’m not coming back, not while you’re here or his dad, not even to swim. The four left the house together, the boys walking apart, Jenny and Charlie running on or trying to walk beside their brother and take part in the conversation. They would not be persuaded to go anywhere else or to do anything else.

Park Road could almost have been part of a village in the country rather than a London suburb; the houses which lined it were genuinely old, not twee, and the trees were a part of the road, not additions to it. You don’t need to be in the country to be affected by weather and nature and land, especially at that age.

‘We’re going to look at a house. You can’t come, you’re not allowed to.’

‘Then you can’t either,’ said Jenny.

‘I want to,’ said Charlie.

The house made an impression, standing out from its surroundings even then, before it was part of a large group of similar houses. It was an expensive-looking dark brick, a square with a section removed to form a small courtyard leading to the front door. The roof sloped quite sharply towards the door, giving the whole an angular appearance, not much altered by the fact that one of the ‘corners’ was rounded and had a long, vertical window stretching almost from the ground to the roof. It was a self-consciously odd design, intended, it seemed, to attract attention.

– How can the wall curve? I want to live here, it’s a good house, better than Eddie’s but no swimming-pool. I hope it’s empty, I hope no one’s there, no one will be there on a saturday, I hope it’s empty.

The boys crept through a gap in the hedge which shielded three sides of the house with elaborate care, followed by Jenny and Charlie, imitating them.

‘We’re not supposed to do this,’ Jenny whispered.

‘Don’t want to,’ said Charlie.

‘Don’t then, go home,’ said his brother.

In the open but failing sunlight, partly hidden by the hedge, they crept up to a window of the house and looked in. At first everything was dark save for a band of sun, throwing the elongated shadows of their heads and shoulders over the carpet. They began to make out a sitting-room, decorated in shades of brown set off by chrome and glass, leather on the chairs, a bare coffee-table, rows of empty, grinning shelves. Where a stereo and a TV might have been there were spaces, waiting to be filled. Through a door could be seen a staircase curving upon itself like a pillar.

‘Isn’t it posh,’ said Jenny, still whispering.

– Dark, warm, smart. That’s what my house will look like when I have one.

The sitting-room in Eddie’s house was decorated like this, in contrast to all the other rooms. It was forbidden to the children, as if it was something fragile or brand-new. To venture into it when the parents were out was considered an act of great daring.

‘Let’s get in,’ said Eddie, ‘we’ll find the back door.’ As he had come nearer to the house he had become more intense, frighteningly so.

Not listening to the objections of Jenny and Charlie, the boys moved around the corner. They saw an expanse of a few acres dotted by piles of bricks, heaps of sand, some machinery and a cluster of wrecked houses, or houses in different stages of construction. It looked as if the buildings were being systematically pulled apart. It was a graveyard for houses.

The back-door, to their surprise, was open. ‘We can’t go in,’ said Jenny decisively.

‘I want to go home,’ said Charlie.

‘Go then, no one’s stopping you.’

Jenny took Charlie’s hand and walked back to the hedge as the boys went cautiously in. It was the kitchen, everything was shiny, a black oven built into the wall, bright chrome fittings, clean white panels, patches of red, it looked like luxury, ‘Like adverts,’ Eddie said. But the impression it gave was unwelcoming, everything too good to use, it was cold, it even smelt new. ‘Let’s break it,’ breathed Eddie, ‘let’s break everything.’

A big, black garden spider scuttled over the spotless draining-board and Eddie raised an arm, whether to kill the spider or to begin breaking things was unclear because at that moment a young man in a light grey suit came into the kitchen and shut out everything but the awareness of his presence. I will never forget that shock, as sudden as Charlie’s howl of pain when the bee stung him, as physical as the cold thrill on diving into the pool. Some things, very few, are vivid enough to close the gap of years and make it seem that they happened to me only days ago.

But he smiled genially. ‘It’s a nice place, isn’t it?’

‘The door was open ...’said Eddie. ‘We’re sorry ...’

‘No harm,’ said the man, his tone not smug or condescending. ‘You can go home and tell your parents what a nice place it is. But you might try the front door next time.’ He smiled, sharing a joke.

The boys thanked him and apologised simultaneously as they left under his eyes, stumbling out of the back door, running once they were round the house, back onto the road and on in no particular direction, laughing and talking excitedly in their relief until they were out of breath. Euphoria had swept away the earlier tension and, sweaty and breathless, walking now beside a busy road, they decided to go back to Eddie’s house for a swim.

There was no hesitation at the edge this time. When they had changed they raced for the pool and took flying leaps into it.

– Aah cold lovely floating a new body, clean.

They soaked off the panic they had both felt and swam races and splashed and ducked each other.

– Like darkness you can feel separate and alone and slow, like darkness you can’t breathe but you can see it. Like water like flying, just for a bit more, hold it a bit longer ...

He could not swim fast but he could swim further than Eddie underwater. He liked to swim underwater, suspended between air and earth in a quiet world, and it was while he was under that Eddie’s father came out of the house.

It was as sudden as the appearance of the man in the kitchen. When he surfaced Mr Fox was shouting at Eddie about trespassing, about thieving, about being responsible for his brother and sister. Eddie got out of the pool but would not look at him though he shouted at him to raise his eyes. In a sudden, shocking movement the red-faced man, infuriated most, it seemed, by Eddie’s lack of reaction, raised an arm, actually baring his teeth, raised an arm and hit him with his open hand on the side of the head. I heard him sigh, a satisfied angry sound, as he watched him fall.

Eddie hit the side of the pool, I could see he hit his head, and he rolled in. ‘Don’t help him!’ shouted his father. ‘He doesn’t need any help.’

I ignored him, perhaps he thought I didn’t hear as I swam over to Eddie. He was not unconscious but I think he must have been a little dazed. His face was contorted and his tears and some of his blood were mingling with the water of the pool. He gripped my arm tightly. ‘Wait, wait, he mustn’t see me yet. Wait.’ There was no fear or pain in his face, only hatred, a child’s hatred, melodramatic perhaps, but quite sincere.

When his father caught his wrist and yanked him out again the only water on his face was pool water. One side of his face was messily streaked with red.

‘You go home!’ Mr Fox snapped, not even looking at me, and then began to shout at Eddie again, determined to get some reaction from him. I pulled my clothes on over my wet body and ran all the way home. I remember the clothes sticking to my skin, the feeling of my feet slapping the pavement, the pain in my chest and the sound of my breath as I forced myself to run on as fast as I could. It was the time when street-lights come on, red against a grey sky, and the side-lights of cars were spreading back a tide of shadow.

Face pressed to the window that night, he saw no spot of light, and he soon turned off his own torch, feeling a little childish. He stared instead at the roofs and the dark shapes of the trees, mimicking the shapes of the heavy clouds above.

When one idea fades, another replaces it. I remember wondering, in bed that night, what would happen if the bed sank instead of flew. Sank into an ever deepening vault. There was always comfort in sleep, and comfort in darkness, death is a house too. I wanted to sink further and further into the pit.

– Further and deeper. What is there so deep?

In the background the quiet sound of the traffic, otherwise only sleep, and – I thought then – forgetting.

Send Letters To:

The Editor

London Review of Books,

28 Little Russell Street

London, WC1A 2HN

letters@lrb.co.uk

Please include name, address, and a telephone number.