‘We’re certain it must be his,’ the phone call had said.

The day was hot. You could see the excavator from a mile away as it crouched on the flatland, a giant locust of yellow metal. We drove at an angle to it along a road as flat and exposed as a causeway until Nick swung the Land Rover off the road and headed it towards the dig. Picks and spades clashed and shuddered in the back and Sally bounced on the seat beside me. She kept her balance better than me. I thought I was going to crack my head on metal or glass.

We stopped at the excavation and clambered out. The air was monstrous with heat. The ground smelt of salt and thick clogging mud. The vegetation was low and fibrous. It felt as if the sea would reclaim all this at any time.

The team stopped work and stood awkwardly around the site, embarrassed and guilty. Nick introduced me quickly and without formality. None of them came forward to shake my hand.

‘This is it,’ he said simply.

It was strange to stand there beside that opened patch of ground. The excavator shovel had scored across it and clawed up long strips which lay beside it, broken and dumped. Beneath the thick dark upper layer were patches where the soil was stained a vivid and surreal RAF blue. I felt heady. The blue was the colour of Asian gods.

‘It’s here all right,’ Nick said. ‘No doubt about it.’

I hadn’t met him before. Sally had talked about him and, like a jealous father, I had sought from her aspects of him that I could criticise. Now he appeared to be more of an organiser than I had suspected (‘a day-dreamer’ I’d scoffed, when I’d heard about his plans, but this was a considerable operation). He had a beard and tinted glasses and a forage cap. He wore jeans and turned-down wellington boots that were caked with mud. Sally had told me he had a genuine flying-jacket which he wore at university, and a genuine RAF tunic he kept locked in a cupboard.

I sensed he knew I was unconvinced and resentful. Sally would have told him, anyway. That was why he was pleasant to me, and that was why he had already implied that he would consider any objection I would care to make. Yet it was clear that, in the end, he would let none of his decisions be swayed by me. Just as he would go his own way with my daughter, so, even if I objected, he would continue and finish the dig.

My father was down there.

Nick went to talk to the operator and the excavator restarted, digging its metal teeth into the wide shallow hole and gouging another solid layer of earth away with a long scraping scoop. The noise of the engine exploded away on all sides. Two of the team swept the earth with metal detectors. The sun was so hot I could feel the blood move in my temples.

‘We calculated all this,’ Nick said. ‘There was an eyewitness. You didn’t know that, did you?’

I shook my head.

‘He was miles away but on a good sightline. He just thought someone else would be doing something about it. We got hold of him almost by chance. A few days with the detectors did the rest.’

‘Wasn’t it reported?’

‘You know how things go in a war. And by the time people got round to looking for it – well, it had buried itself. These days they’d be on it like vultures. Souvenir hunters strip crashed aircraft within a couple of hours now. Even on mountains. And there’s no doubt that it’s down here. We’ve followed the scatter pattern very closely. A complete disintegration would have been different.’

Sally came over to stand beside me. Her shirt was sticking to her. One of the team kept looking at her but looking down when he saw me watching him. It was natural enough but I still had a complex reaction to such everyday glances. It was compounded of jealousy, puritanism, protection and a sense of freedom. My feelings about her relationship with Nick were even more contradictory.

‘There’s a kind of standard pattern to the way they crash,’ she said, ‘Nick’s quite an expert.’

‘So I hear,’ I said drily.

‘We found the impact zone a few feet back,’ Nick said. ‘The Spitfire would have hit there’ – he pointed back to behind the excavator – ‘and ploughed into the ground just here.’ He pointed to where the excavator claw was scraping and peeling the ground. ‘We don’t think it can have broken up all that much. There’s a layer of harder subsoil over there. See the slight change in vegetation? That’s the line of harder soil. Well, rock deposition mostly, although covered over with sedimentation by now of course. That probably brought it up short, concertina’d it.’

A metal detector whined and from the soil one of the team picked a featureless twist of metal the size of his hand. He brushed the damp soil from it. ‘Could be anything,’ he said.

‘The way I see it,’ Nick continued, assisting his explanation with hand movements, ‘he must have come back over the sea, probably flying fairly low. We know the rest of the squadron went into a dogfight and that he went with them. What happened after that we don’t know. Officially, of course, he just went missing. So he would come back in from the sea, maybe low on fuel and losing it, maybe hit and wounded, maybe being pursued – although we don’t think so. Maybe he was dead at the controls. He came in’ – Nick’s hands sheared through the air – ‘and hit.’ He smacked one hand into the other.

I nodded. He pointed to some earth that was slipping over the side of the grab. It clung together unnaturally. It was not the same consistency as the rest of the soil and did not take the sunlight as it should. ‘Engine oil?’ Sally asked.

Nick nodded. ‘We’re just above the point of rest. The main body of the plane will have been gradually sinking. After all this time it could be a good way down.’

Enthusiasm took him and he held my sleeve as if wishing to convert me. ‘Just picture it,’ he said, and I knew he would be able to hold an audience just by the urgency in his voice, ‘the Spitfire coming low and fast out of the sea, with the sun as high and as hot as it is today. Maybe the plane would be trailing smoke, maybe even it would be on fire, the pilot willing himself home and yet unable to make it –’

He broke off as if he had suddenly realised who he was talking about. ‘Sorry,’ he said, and I wondered if he was speaking to Sally rather than me.

‘It’s all right,’ she laughed, ‘even Dad didn’t know him.’

‘He may have baled out,’ Nick said to me.

‘And drowned at sea?’ I asked. I was shocked at how bitter I sounded.

He shrugged.

‘Or he may still be down there,’ I said.

‘I can’t think about that,’ Sally said quietly. Another piece of metal came up and she bent to examine it. ‘What is it?’ she asked.

Nick began to scrape off the caked earth with the side of one hand. ‘It looks like a wing spar,’ he said. ‘Let’s see ...’

I looked out across the immense flatness to the distant sea. A pair of oyster-catchers called in the distance. I couldn’t help reflecting that this man who had gained control of my daughter was now, in a way both mercenary and perverse, gaining control of my father as well.

All that long afternoon they worked. I believe they expected me also to lend a hand, but nothing would have induced me to join the dig. I sat at a distance from it, both fascinated and repelled by it, sometimes tugging at the coarse tubular grass. It smelled of rankness, as if its existence was indifferent to any subtle ecology.

The sun declined across the land, swivelling the excavator shadow, but the humidity and the heat remained high. Twice I saw thunderclouds begin to form, and once I thought I saw distant lightning flash broadly and thinly across the horizon, but no noise came after it. On the next occasion we all heard a distant grumbling echo, like thunder, and raised our heads to an unexpected and temporary cool breeze. But the clouds broke apart under their own pressure and dispersed, and the heat continued to oppress us. Apart from a thermos of coffee, they did not break from work but continued to dig methodically towards the plane. I’d placed a tube of grass between my teeth and it had tasted bitter, so I was pleased with the coffee even though it reminded me how hungry I was.

Every now and then a fragment of metal was unearthed – a piece of the fuselage, a strip of rotted aluminium, fragments of alloy that made the detectors whine and yelp. Even Sally took her turn at the excavator controls. Nick shouted up at her. She handled them with a confidence and skill that surprised me. I wouldn’t have been anything like as good at them.

Hunger and the heat made me feel lightheaded. They must have felt worse. Nick was reluctant to give up for the night, but the light was draining out of the sky and that was obviously what he had to do. The trench was wide and several feet deep. The soil at its bottom had been stained blue with the rotted aluminium.

‘One last scoop,’ he said. They made it and unearthed the tip of the tailplane. It protruded from the soil at the bottom of the trench. I felt weak, loose-bowelled, slightly drunk.

The old inn (it called itself a hotel) faced the open landscape. It would be hard to live there in winter. Even in summer the building seemed dangerously exposed, the highest point for miles, its chimneys the first to be struck by lightning or bowled over by wind. Nick used it as a base. Approaching from a distance, I imagined it deserted, but its remoteness and relative antiquity drew customers from miles away who raced to and from it at full throttle along straight flat roads. We sat in the bar with basket meals and beer. I was crammed between Nick and Sally in an unconscious parody of the position of guest of honour.

I didn’t join in the conversation much. The others, made slightly drunk by the day, had lively but not very coherent discussions about aircraft ‘recovered’ (their word), about search techniques and disintegration patterns, bomb-detectors and metal-detectors, Mason’s classification of locatable wrecks. Someone reminded Nick that he had promised to shave off his beard if this one was found, and everyone laughed when he tried to back out of his promise.

It was all a long way from my war. Mine was an abstract war. It could never be found among documents and memoirs and pieces of wreckage; it was located in the imagination. I thought of it in terms of grand abstractions and eternal principles – glory, heroism, triumph, grief, belief.

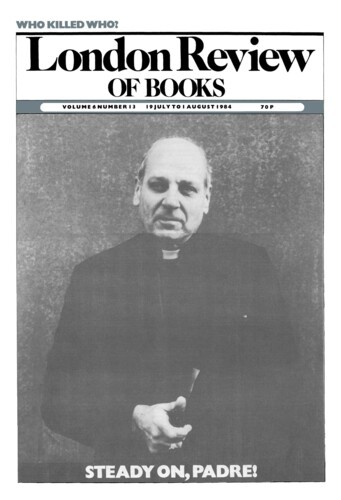

I was born after he vanished. All I knew of him were my mother’s photographs and memories. His image stood in a frame on the sideboard. It was a studio portrait, with the photographer’s name an extravagant flourish across a lower corner. My father is seen in head-and-torso shot, wearing his cap and tunic. The focus is soft, almost too soft. And, as was common at the time, the colours are watercolours, hand-painted and unreal. I remember that, not realising how it had been painted, I thought his skin incredibly soft and uniform, like that of a doll. His eyes are of porcelain blue, the blue of distant calm skies, their centres are as circular as targets. His uniform of RAF blue is pressed and exact, the golden wings as romantic as buccaneers’ gold.

He had taken off one day and never been seen again. According to the books, he was Missing Presumed Dead. The way my mother talked about it his disappearance had been mysterious, destined, even heavenly.

Later the pub talk turned to the lives they had mapped out after university. I sat still and said even less.

Nick took me round to the back of the inn across the dark courtyard. He unlocked the door to the old stables and it creaked sharply, as if rust would snap the hinge. ‘You’ve got to keep it under lock and key,’ he said, ‘it’s amazing what people will steal.’

There was no light in the stables. He directed a torch around the flaking white walls and onto a floor of uneven stone. Bits of my father’s aircraft lay scattered across it with identifying tags wired round them as if on corpses’ toes. When Nick moved the torch the shadows leaned expressionistically.

‘You see how much we’ve got up already,’ Nick said. I nodded. His face, lit from below, was washed with melodramatic highlight and shadow, like a fortune-teller’s over a crystal ball.

‘Don’t think they’re just being dragged out of the earth,’ he said, ‘no, we’re doing a very professional job. I could show you a chart with all the positions noted. By the time we’re finished it will be possible to draw an exact representation of this plane’s breakup and scatter pattern. We plan to put it on a computer in three-dimensional graphics. It could be a great help.’

‘To who?’

‘Other diggers. Crash investigators. Farmers.’

I picked up a piece of the metal and looked at the tag. The code it carried was meaningless to me. ‘What would the other customers in the pub think of this?’ I asked, testing the metal’s balance and weight.

He shrugged. Under the beam the spars and fragments appeared to shift. ‘Pieces of militaria for some. Scrap metal for others.’

‘You see it archaeologically.’

‘That’s right.’

‘Or maybe more like a grave-robber.’

‘You shouldn’t try and put me down so much. I can understand your feelings.’

‘Really?’ I asked.

‘I see it all practically,’ he said. ‘Not romantically.’

I put the metal down.

‘You think it’s your past?’ he asked. ‘Your personal untouchable sacred past?’

‘If it is I can’t recognise it. It’s too ... substantial. Too tangible. I can’t tell you what any of those pieces are or what they have to do with the workings of an aeroplane or what they had to do with my father’s death.’

‘I can name every one,’ he said softly. ‘Would you like me to prove it?’

‘You needn’t try to make me feel guilty,’ I said. ‘I don’t feel I should know.’

He had already drawn from me more than I ever thought I would give. I was reluctant to confess that, although my rationalism told me otherwise, my imagination had never quite grasped the fact of the aeroplane coming down. Nick was right. In my mind he had disappeared into the blue, melted into cloud. I had fed on all those post-war films in which handsome young airmen vanish into the skies. If he had ever come to earth then a shower of rain seemed more fitting than these poor beaten pieces of metal.

‘I’m sorry,’ Nick said, ‘I should have realised you would take this hard.’

‘I’m not taking it hard. I’m being very objective and reasoned and understanding about the whole thing.’

‘Yes,’ he said, ‘sure.’

Back in the bar I felt compelled to talk. The long day had loosened my tongue. And I refused to let Nick buy me a basket meal just because he bought all the others; I would pay for my own. ‘Take your chance now,’ he said, ‘I’ll be a different person when the beard goes.’

Perhaps I also believed the extraordinariness of the day had touched me with fluency. I sought out Sally like a man driven to confession. She sat there and listened while I talked about the war, about the courage of fighter pilots and the odds against them. I must have used all the old phrases. To me they were apt, exact and alive; to her they may have rung as hollow as lies.

‘But you never knew him,’ she said.

‘Of course not,’ I said, ‘that’s not the point.’

‘Perhaps that’s exactly the point.’

‘I know enough about him. About his background. Where he was born, how he grew up, the university he went to.’

‘You don’t know what he was like as a person. He may have been someone you simply couldn’t get on with.’

‘He was only a young man.’

‘He was about Nick’s age.’

I sat and looked at my drink, aware as I did so that this too was a formulated reaction, a cliché that she would interpret. Despite their apparent concern for me, I was little to them. An irrelevance. A hollow man, his skull stuffed with dated ideas, unfashionable morals. I was a jackal returning to a stripped and empty carcass.

‘Why do you think I’m here?’ I asked.

‘That’s easy. Because I told Nick that you just had to be here. You’re part of the chain of events. And of the ritual.’

‘I’m here because of a sense of duty,’ I said. ‘And you?’

‘Because of Nick. And because he’s infected me with his passion for old engines, deserted crash sites, all the paraphernalia of these ... celebrations.’

‘Don’t you feel anything personal? Some link with that man down there?’

‘If he’s down there. We still don’t know. No, I don’t feel anything much for him. I feel more for you. I keep thinking of you as a character in some second-hand, careworn myth. I know who you are, Dad. I made the discovery years ago. You never had that advantage.’

She took a drink, and smiled quietly.

‘Think about it,’ she said, ‘it’s in all the best myths.’

‘Whose idea was this?’ I asked. I could hear my voice develop a sudden rasp.

‘I told Nick a long time ago. He’s been working on it since then. All the time coming closer and closer.’

‘When you first told him, were you lovers?’

‘No. It’s what threw us together.’

I went to bed and couldn’t sleep. The room was narrow and hot, and it didn’t cool when I opened the window. For a while I watched the sky, waiting for a storm, but it had receded further. I could even see stars. You could navigate by the sky on a night like this. Far away towards the horizon the lights of an aeroplane passed in geometrical leisurely silence.

I sat on the bed and drew myself up like an unborn child but with my wrists on my forehead. I thought about him. About his photograph and about the heap of formless jetsam in the stable. At the edge of speculation I believed he would be here somewhere, sitting in the corner of the room with that exact blue uniform and film-star skin.

Of course there could be nothing there. It was just another of my outmoded fantasies, my own hackneyed way of trying to cope.

I may have slept then. Certainly I conjured images as contradictory as a dream. I am reaching out, one hand splayed, through fire that crumbles like soil to the touch. I am reaching down into water or air to find nothing, to touch the rounded smooth skull of an ancient burial. The cockpit is empty, the pilot dispersed, dissolved, beyond touch or thought. We tumble his bones into a black plastic bag to await the coroner. As it lies beside an open grave a wind will fill it like a black sail.

An hour or so after going to bed I heard noises from the next room. It was Nick’s room and I knew the sounds were of he and Sally making love. I pressed myself to the wall like a climber on a sheer face. I could feel their rhythm passing through it, vibrating steadily in a heavy, laboured pulse. While they coupled one of them would be braced, anchored against it. I imagined the force of their love-making absorbing itself into the fabric of the building, echoing down the walls and, fainter and fainter, vanishing into the earth.

I could hear their sighs clearly. They were light and high. I tried to imagine them together, but I had not seen her naked since she was a child and her body was as big a mystery to me as my own mother’s. I stood splayed against the wall feeling my face become motionless, bloodless.

The climax, when it came, was low, almost unheard.

I sat back down on the bed. I had known they were lovers, had reminded myself constantly of that fact. But hearing it gave me a sharp and unhealable wound. It cut me with an edge of loss and passed time.

And there was also release.

When I heard her open the door I stepped out into the corridor. It was dark, secret. Her face was a pale smudge in the half-light, unformed. I took her arm. It was warm, and flushed with blood. Her eyes were wide, both apprehensive and challenging.

I realised that she had wanted me to hear.

The landscape looks different at night. The horizon is closer, as if the earth is tilted around us and we are driving to the centre of a broad, vast, shallow bowl.

Sally drives the Land Rover quickly but efficiently. Picks and spades rattle in the back.

When we get to the site there is a cool, easy breeze blowing from the sea. The excavator stands beside the opened earth. Its colour has been bleached by the night and it looks less bulky. Deathly.

I look up. There are still a few stars.

We reverse the Land Rover until it stands beside the hole and then rotate the swivel light on its roof so that the beam is directed down into the disturbed earth. The plane’s tail protrudes like a sharkfin. We start the excavator and Sally takes out great slices, wedges, slabs of earth from above the fuselage as I shout guidance.

Soon it is obvious that only spadework is left so we get down into the wound and start digging.

We work in a rhythm, clearing the soil away from the main body of the plane and piling it to one side. Sometimes the earth makes a dark sucking noise as the spade blades slice it, but it stays compressed in thick cakes like peat. And it always falls heavily.

The earth slips and makes soft, unreal noises under boot soles.

We come across bits of metal and softer, flexible material that could be anything. Decayed rubber, padding, clothing. We throw it to one side. We lob, hurl, cast aside the finds.

We wreck Nick’s system as surely as the plane itself has been wrecked. I don’t care if it’s beyond recovery. I don’t care that the scatter pattern will never be plotted, the computer chart never be made.

After only a few inches we smell the cold. It catches in the back of the throat like the cold of an opened grave. There are unrecognisable smells released from the earth – sharp, like cut metal, and rank, like lifted flagstones.

The lights throw mountains and gullies on the bottom of the dig. Some are ridged with blue almost as if a painter has walked the scar. At times we push our spades into smooth wells of blackness, as black as carbon, as pitch, not knowing what we are cutting into. The ground sighs. The ground is broken by us and reformed.

We bend and heave and sweat and wheeze. The spades strike, glance, scrape on metal. The tailplane juts up like a marker, a monolith. A blade.

Just before the dawn I see a figure walking towards us. It does not deviate from its path but walks straight towards us across the flat land. I can watch it coming at us in the thin but strengthening light. From its build, from its walk I can tell that it is a man. As he comes closer I can see that it is a man in an RAF flying-tunic. Closer still and I can see his skin, given an unreal uniformity by the light, his face, which is clean-shaven and young, his eyes, which are wide and direct. He stands at the edge of the dig, without speaking, looking down, not entering. He is like a man outside a magician’s circle.

The dawn comes up without drama across the distant unseen sea.

I turn away and push my spade into the blue.

Send Letters To:

The Editor

London Review of Books,

28 Little Russell Street

London, WC1A 2HN

letters@lrb.co.uk

Please include name, address, and a telephone number.