In 1949, a moment when I was editing the novel pages of the Times Literary Supplement, a book came in called A Mine of Serpents, author Jocelyn Brooke. The name was familiar on account of a previous work, The Military Orchid, which had appeared the year before, and received unusually approving notices. I had not read The Military Orchid, partly because there was a good deal to do reviewing other books, partly because (being in that respect like Wyndham Lewis’s Tarr, for whom ‘the spring was anonymous’) I thought a work much concerned with botany sounded off my beat.

Quite fortuitously, I reviewed A Mine of Serpents for the TLS myself, treating it more or less as a novel, which it was to only a very limited extent. There was some excuse for that, as a note at the beginning stated that the book was ‘complementary’ to The Military Orchid, rather than a ‘sequel’, and certain ostensibly fictional characters occurred in a manner to suggest later development of a contrived plot. I did not grasp that here was the second volume of a loosely-constructed autobiographical trilogy, slightly fictionalised. The review now strikes me as a trifle pompous, but I recognised Brooke’s talent at once, and remarked that the epigraph from Sir Thomas Browne – ‘Some Truths seem almost Falsehoods and Some Falsehoods almost Truths’ – contains ‘in a sense justification of all novel-writing’.

I knew nothing of Jocelyn Brooke himself, except what was to be gathered from this book. He was, in fact, then just about forty, and had recently emerged from the ranks of the Royal Army Medical Corps, in which he re-enlisted two years after the end of the second war. A collection of poems by him had appeared in 1946, but The Military Orchid was his first published prose work.

In the same year, 1949, Brooke brought out The Scapegoat and The Wonderful Summer, neither of which came my way at the time – nor were part of the trilogy – but in the spring of 1950 I reviewed his Kafka-like novel, The Image of a Drawn Sword, and, in the autumn, the trilogy’s third volume, The Goose Cathedral. By that time I had marked Brooke down as one of the notable writers to have surfaced after the war.

In those days reviewing on the TLS was unsigned, so there was no question of Brooke having known about my liking for his work when in 1953 an article by him appeared in one of the weeklies praising my own first novel, Afternoon Men, published more than twenty years earlier. Afternoon Men had, as it happened, been reprinted about a year before, but when I wrote to Brooke expressing appreciation of this unexpected bouquet, he turned out to be unaware of the book being in print again, having merely reread his old copy, and rung up a literary editor on impulse. In due course we lunched with each other, met from time to time afterwards (though never often), and continued to correspond fitfully until Brooke’s death in 1966.

All writers, one way or another, depend ultimately on their own lives for the material of their books, but the manner in which each employs personal experience, interior or exterior, is very different. Jocelyn Brooke uses both elements with a minimum of dilution, though much imagination. However far afield he went physically, his creative roots remain in his childhood. He was by nature keenly interested in himself, though without vanity or the smallest taint of exhibitionism.

Brooke might, indeed, be compared with a performer at a fair or variety show (perhaps to be called Brooke’s Benefit), who arrives on the stage always with the same properties and puppets. The first backdrop is certain to be the landscape of Kent, into which the author is wheeled in his pram by his nurse, his mother in attendance. Soon he is lifted out of the pram, and presents himself as child and schoolboy. There are botanical effects; sometimes fireworks. Soldiery of the Royal Army Medical Corps wait in the wings to provide mainly comic relief. Occasionally the scene is changed, though rarely for long: a London pub; the houses and flats of perhaps rather dubious friends; a camp in the Middle East or Italy; but sooner or later we are back among the hopfields, with the neighbours and the family wine business; the bizarre antitheses of a highbrow childhood in unhighbrow surroundings. In short, the facts of Brooke’s life are more than usually relevant.

Bernard Jocelyn Brooke was born 30 November 1908, third child and second son of Henry Brooke and his wife Mary, née Turner, the youngest of the family by ten years or more. Both his grandfathers had been wine merchants, also his father, who had started life as a solicitor. Brooke’s elder brother, after ten years as a regular officer in the Royal East Kent Regiment, The Buffs, joined the firm too, and for a while so did Brooke himself.

Earlier generations were parsons, in the professions, yeoman farmers. A less run-of-the-mill heredity is suggested by the portrait (1826) of Great-Aunt Cock with her two little dogs (reproduced in one of Brooke’s books); also by the box containing the literary remains of a great-grandfather, crony of Thomas Hood’s, Joseph Hewlett, a tipsy vicar with 18 children, who kept body and soul together on a minute stipend by writing facetious novels under the name of Peter Priggins.

The Brookes’ wine shop – always known as the Office – was at Folkestone. They themselves lived at Sandgate, a more socially eligible strip of coast to the west. They also possessed an inland cottage at Bishopsbourne in the Elham Valley, where in the summer they retired to ‘the country’. Bishopsbourne was the neighbourhood to provide Brooke’s earliest memories, most beloved centre for imaginary adventure in childhood, hunting-ground for flowers, the very heart of the Brooke Myth.

From earliest days Brooke used to overhear grown-ups muttering that he was ‘not strong’, a condition that must have caused specially uncomfortable concern to parents who were converts, though not fanatical ones, to Christian Science. At a later date, Brooke’s childish problems would no doubt have been looked on as largely psychological. The household, without being in the least professionally intellectual, was not without all literary contacts, not on visiting terms with Conrad, who had a house by Bishopsbourne, but the two elder children used to attend the parties of a Mr Wells, who turned out to be H.G.

Brooke’s nanny (from some early mispronunciation always known as Ninny), by creed a strict Baptist, was a preponderant figure in his life, and (like the country round about) remained so virtually to the end of his days. He was an intelligent child, painfully sensitive and, like many such, quick in some directions, slow in others:

Often, but not always, the botanophil is precocious. A family legend relates that myself, at the age of four, could identify by name any or all of the coloured plates in Edward Step’s Wayside and Woodland Blossoms ... not content with the English names, I memorised many of the Latin and Greek ones as well. Some of these (at the age of eight) I conceitedly incorporated in a school essay ... The headmaster read the essay aloud to the school (no wonder I was unpopular).

A consequence of the touch of crankiness in the Brooke home, which went side by side with a good deal of conventionality, was that Brooke was not allowed to eat meat in his childhood (Ninny asserted it ‘caused sand in his water’), a curtailment which, when he first went to school, nearly resulted in death from starvation, as nothing was added to his plate of routine vegetables, a component of the menu at its lowest ebb in school fare during the first war.

Thought of being sent to school had in any case clouded Brooke’s early days, and when the blow fell, the reality confirmed his worst fears. A day-school was just tolerable, but he was not at all happy at a local preparatory school, which sounds little different from most prep schools of the time. The real disaster came when he entered King’s School, Canterbury (alma mater of Christopher Marlowe, Somerset Maugham, Patrick Leigh-Fermor), from which Brooke ran away in the first week. He was sent back. The second week he ran away again. The second withdrawal marked the termination of his residence there, which had lasted less than a fortnight.

Brooke’s parents – whom he more than once designates as long-suffering – accordingly decided to transfer their younger son to Bedales. In this milder atmosphere, coeducational and ‘progressive’, he found relief: indeed, was surprised by his relative contentment. He has left some picture of life at Bedales, where sex was condemned as ‘silly’ (I remember a female Old Bedalian telling me that in her time one girl was so ‘silly’ she had a baby), and Brooke does not disguise that this doctrine did not provide a complete answer to all sexual difficulties.

At Bedales (in face of some official discouragement) Brooke first read Aldous Huxley, deciding he was himself a disillusioned Huxley character, though the requirements of that stance were not always easy to maintain at school. ‘The Huxlcian poison continued to circulate in my veins for the next ten years or more: indeed, I think I have never succeeded in finally excreting it from my system ... I idolised him when young, and if I find his later work hard to “take”, my difficulty is partly due, perhaps, to the immense expectations which his earlier books aroused in me.’

Brooke, like his novel-writing clerical forbear, Peter Priggins, was up at Worcester College, Oxford, where he often felt lonely, but seems to have lived the fairly typical life of a Proust-Joyce-Firbank-reading undergraduate. Oxford memories soon became blurred for him, but he remembered sending an article on the subject of Oxford Decadence to the Isis, which was accepted by the then editor, Peter Fleming, but no meeting took place, a record of which might have been enjoyable.

On coming down from Oxford, the Twenties now moving fast towards their dissolution, Brooke, prototype (as he himself always emphasises) of the all-but-unemployable young man of the period, came to London. He worked for two years in a bookshop in the City. When for one reason or another that job terminated, he decided to try the family business, from which his father had by then retired, the Brooke parents now living at Blackheath. Brooke found himself dreadfully bored writing out invoices for wine orders, nevertheless he drudged away at it; in a general effort to take life more seriously he also attempted to grow a moustache. The family business turned out not to be the answer, nor various other employments, and he had some sort of breakdown.

Brooke, as this account of his beginnings shows, was very much a Child of the Age, anyway a highbrow child. The curious thing is that he did not, like so many young men of that category, bring out a first novel telling a hard-luck story. It is difficult to believe he could not have achieved publication had he wished. On the contrary, no book by him appeared before the war, and, when his own kind of autobiography went into print, though its roots were in a richly self-pitying epoch, it was entirely free from that element.

To what extent Brooke returned from the war to an accumulation of notes for books is not clear, but the fact that his eventual output included 15 works published – some separated by only a few months – between 1948 and 1955 suggests he had at least made up his mind about a lot of literary possibilities. Among these later volumes was another collection of poems (Brooke’s verse was competent rather than inspired), an Introduction to the Journals of Denton Welch (that gifted petit maître, as Brooke calls him, who died at the age of 33), some technical writing on botany (though Brooke always insisted he was only an amateur among real botanists), and a surrealist collage in the manner of Max Ernst.

In various thumbnail sketches of himself taken from different angles during early London life, Brooke sardonically presents a typical young intellectual of the period, toying rather ineffectively with the arts, writing poetry intermittently, trying to fit himself in among the homocommunists (a useful portmanteau word Brooke coined, later adopted by Cyril Connolly in Horizon), but Communism proved wholly unpalatable, and politics, like efforts to grow a moustache, were given up. He might, perhaps, in his own manner, have been called an existentialist, disliking the pressure of all abstract ideas, but he preferred to define himself as a futilitarian.

When war came in 1939 he enlisted in the Royal Army Medical Corps. The Army, recurring throughout most of his books, was to provide some of his best material. Again, though his military service must often have been far from comfortable, he is without the least self-pity. In fact, feeling after a time that life was too easy, he volunteered for the branch of the RAMC treating venereal disease – in army parlance, the Pox-Wallahs. He returned to the VD branch when he rejoined after the war, and managed to get posted to Woolwich, conveniently near the family home at Blackheath.

The success of The Military Orchid with the critics, the possibility stemming from that of finding employment in the BBC, the newly-granted permission for a soldier to ‘buy himself out’, combined to bring to an end Brooke’s second round of soldiering, though, like the man in the Kipling poem, Brooke felt the Army pulled at his heartstrings. He had found it much changed after the war, and the National Servicemen were impressed by his five medal ribbons, even if unable to understand this second voluntary acceptance of barrack routine.

From the moment of returning to civilian life again, Brooke settled down to write, in due course retracing his steps to Ivy Cottage, Bishopsbourne, where he lived with his mother and Ninny, neither of whom died a great many years before Brooke himself. He was therefore in the end established as nearly as possible to childhood circumstances, at the very focus of the magical world he had himself created.

The Military Orchid is the opening act of the Brooke variety show referred to earlier. All the basic Brooke constituents are here introduced in his search for the rare orchid of this name (with its closely-related fellows, some almost equally rare, some relatively common), its very designation making a link with war, and all sorts of unexpected people and places. Brooke has the gift – just as some musicians can write of music in a manner intelligible to the unmusical – of making botany intelligible to the unbotanical. Early childhood, school, the Army, all come into The Military Orchid, but not yet Oxford.

The title A Mine of Serpents refers to a firework, thereby introducing another preoccupation of Brooke’s, second only to botany. He was obsessed by fireworks until at least the age of 15 (relations beginning to raise eyebrows at him as ‘too old for that’), and he never lost his love for feux d’artifice, one of the best displays he ever saw being in Italy at the end of the war, when the crowd abandoned itself to a delight as uninhibited as his own.

A Mine of Serpents, without losing sight of life in Kent, recalls Brooke’s Oxford, fictionalising some of his contemporaries. He glances at an Italian holiday; then returns to days in the Army. Brooke is not, I think, at his best as a writer in projecting undergraduates, a hard enough assignment, and these friends, even after they come down from the university, never quite take on substantial enough shape. It is the occasional autobiographical passage that holds the attention.

Brooke always appeared to have satisfactorily resolved his own homosexuality in life, but in his books, perhaps because at that date some discretion had still to be observed, he is at times less at case, veering between satire and a kind of embarrassed uncertainty in a theme that recurs: the hearty queer, perhaps an army officer, who pretends to be otherwise, but has designs on the narrator. This is perhaps to say no more than that Brooke was simply more skilful at his own particular art than in the give and take of the traditional novel.

The Goose Cathedral, third volume of the trilogy, continues to lean towards the novel-writing end of Brooke’s method, with some amusing vignettes, though again I prefer the straight autobiography. The book is named after the lifeboat station at Sandgate, a small grey neo-gothic building by the shore, which in childhood marked one of the limits of Brooke’s daily walks with Ninny. An Oxford friend came to stay when Brooke was older, and, on account of the flock of geese that made a habit of pottering about on the shingle in front of the lifeboat station, the two young men named the place the Goose Cathedral. Later the Goose Cathedral was for a time inhabited as a seaside cottage, then transformed into a tea-room, cropping up again at intervals throughout Brooke’s life, a typical symbolic landmark in Brooke lore.

One of the few books by Jocelyn Brooke which, though the action takes place in Brooke’s familiar Kentish countryside, can unquestionably be listed as a novel, the story being told in the third rather than first person, is The Image of a Drawn Sword. Even here a form of autobiography is not entirely lacking, because in place of Brooke’s physical experience, a kind of vision of the fantasies that sometimes haunted his mind is set out, especially fantasies about the Army.

Reynard, the hero – perhaps rather anti-hero – has been invalided from the Army during the war, and, living in a cottage with his widowed mother, works in a bank in the neighbouring town. Places like the Roman Camp Priorsholt, The Dog (a pub) in the neighbouring village of Clambercrown, which occur in Brooke’s other works, are mentioned in the story.

A young regular officer, who has lost his way, comes to the cottage. He has something to do with the local Territorials. There is the faintest suggestion – better handled than in some of the other books – of mutual sexual attraction, and he and Reynard become friends. The officer tries to persuade Reynard, who is not wholly unwilling, to join the Territorials. Later Reynard attempts to speak with this army friend on the telephone, but for some reason he seems never available.

Reynard continues his efforts to get in touch, and, while he does so, finds it assumed that he himself has already in some manner gone back to the Army. Not only that, but a war has broken out in the neighbourhood, though no one seems to know who the enemy is. Reynard’s friend seems constantly rising in rank, while Reynard suddenly finds himself treated as a deserter. The book ends with his arrest, facing a sentence of a hundred lashes and a fortnight’s field-punishment.

The Image of a Drawn Sword, in its way not inferior to Kafka (though Brooke had read no Kafka at the time the novel was written), has a haunting sinister quality very well maintained. One wonders if the whole theme came to birth when Brooke was in truth trying to make up his mind whether or not to join the Army again. The Dog at Clambercrown (1955), perhaps Brooke’s best book, defines some of these emotions, crystallised by a fellow private remarking: ‘Anyone’d think you liked the army.’

As it happened. Pte Hoskins’ unlikely hypothesis was perfectly correct: I did like the army – though ‘like’ is hardly an adequate word to describe my feelings about it. ‘Love’ would perhaps be nearer the mark, though here again the word required qualifications, for my liaison with the armed forces (and I use the word in its erotic rather than military sense) was by no means a starry-eyed, spontaneous affair which the word love too easily suggests. It resembled, rather, the kind of relationship described by Proust, in which love itself is apprehended, so to speak, only in its negative aspects the pain of loss, the absence or infidelity of the loved one, the perverse satisfaction of possessing (like Swann) some woman who isn’t one’s type, whom one doesn’t even like, but with whom one has become so fatally obsessed that life without her is unendurable.

Soldiering had become a habit with me – out of uniform I felt lost, uprooted, a kind of outlaw with no fixed place in the scheme of things. During the two years since my demobilisation I had suffered from a growing sense of loss and self-betrayal: I had cast off my mistress – glad enough, at the time, to be free of her thraldom: yet I knew that, despite her tantrums, her cruelty and her possessiveness, I loved her still. Sometimes, passing a recruiting office, I would feel the old nostalgia creeping over me, and I would experience a masochistic impulse to throw myself, once again, at the feet of my lost love. She would, I knew, be ready to take me back – exacting and possessive as ever, but prepared to let bygones be bygones.

Brooke’s taste in writers was essentially that of his generation – the debt to Proust is freely acknowledged in the above passage – and the writers he knew, he knew well. There is acute literary criticism scattered about in his own books, some of which may be quoted. For instance, on James Joyce in The Dog at Clambercrown, which opens with Brooke reading Ulysses in the plane on the way to a holiday in Sicily:

Ulysses, I suppose, is the most fascinating and the most devastatingly boring novel ever written ... I remember, many years ago (at the period when Finnegan was appearing serially in transition), reading a poem by an undergraduate in some university magazine or anthology in which the poet describes Joyce as hunting in a drain for the ‘lost collar-stud of his genius’. The image still seems to me – as it seemed at the time – an apt one; for Joyce’s genius was, I believe, of a minor order – he lacked the power and range of the great novelists, and his later work is chiefly distinguished by an infinite capacity for taking pains.

When Brooke arrived at Syracuse he stayed in the house of a (female) friend, whose library was stocked with English books published between 1905 and 1925. As the weather was wet and cold, Brooke embarked on a reread of D.H. Lawrence:

Aaron’s Rod (much praised in its time) struck me, quite simply, as an abysmally bad novel ... The Rainbow: the first chapter seemed magnificent; after all, I decided, Lawrence had everything – a genius for evoking landscape, a sense of character, a marvellous apprehension of human relationships. Yet after a further chapter or two I was firmly bogged down: the prose became more and more turgid: more and more repetitive ... Yet there are magnificent passages in The Rainbow – as there are in Women in Love, its sequel. If only, one feels, he could keep it up! But he couldn’t ...

Lawrence’s ‘secret’ – if one can call it that – was, I suppose, that he was profoundly homosexual: but his lonely, puritanic, lower middle-class upbringing prevented him from coming to terms with his own homosexuality ... Sons and Lovers, The White Peacock, a few of the short stories, and a handful of memorable poems – it is these out of Lawrence’s enormous output which seem most likely to survive.

In The Military Orchid Brooke reviews the capabilities of famous writers and poets in the field of botany. Here Lawrence, who loved flowers and knew about them, comes in for high praise. Oddly enough, Proust knew about flowers too, though he rarely described them for their own sake, liking to use them as analogies for human behaviour – for instance (in the context of ‘hermaphroditic plants’), the moment when M. de Charlus first grasps that the ex-tailor, Jupien, is homosexual, and himself gets to grips.

Matthew Arnold, usually accurate in his botany, slips up by calling the convolvulus blue, though he corrected that to pink in later editions of the poem. Keats, admittedly unable to see what flowers were at his feet, nor what soft incense hung upon the boughs, was inclined to confine himself to vague generalisations about violets and eglantine; Shelley was equally equivocal in botanical imagery. Clare and Crabbe are justly famous in the realm of Flora, though Brooke doubts whether Crabbe’s ‘dull nightshade hanging on her dead fruit’ in Suffolk was indeed Deadly Nightshade; in that country more likely to be the harmless Black Nightshade, or even Bittersweet.

Shakespeare comes out with high marks for being explicit, though Elizabethan nomenclature has sometimes changed.

long purples,

That liberal shepherds give a grosser name,

But our cold maids do Dead-men’s fingers call them.

Millais, says Brooke, painted the Purple Loosestrife in his picture of Ophelia, which was never called Dead-men’s fingers, nor for that matter by any grosser name: ‘Dead-men’s fingers, in fact, refers to one or other of the palmate-rooted orchises, and is also loosely used for the Orchis mascula, one of the round-tubered species, all of which are given “grosser names”, not only by liberal shepherds, but by the early herbalists; the reason being that the two tubers suggest a pair of testicles.’ One is glad to learn that, as in the days of King Lear, samphire may still be gathered on the Dover cliffs.

I was never a close friend of Jocelyn Brooke’s, but we corresponded quite often, and he was one of the people to whom one wrote letters with great ease. He speaks more than once of his own liking for that sort of relationship, a kind that did not make him feel hemmed in. There are several incidents in his books when the narrator refuses an invitation from someone with whom he is getting on pretty well, so that it was no great surprise when, a few months after Brooke had stayed with us for a weekend, he politely excused himself from another visit on grounds of work. The reason may have been valid enough, writing time is always hard to conserve, but one suspected his sense of feeling ‘different’, an unwillingness to cope with face-to-face cordialities, which might at the same time be agreeable in letters.

Brooke liked a fair amount to drink, and, after lunching with one, was inclined to say: ‘Shall we be beasts, and now go to my club, and have another glass of port?’ In 1964, less than two years before his death, my wife and I were staying in Kent, and went over to see him at Bishopsbourne. We lunched at the Metropole in Folkestone. All this territory was the hallowed ground of Brooke legend. Writing of Beatrix Potter, Brooke says that as a child the world of Mr Todd and Jemima Puddleduck had seemed ‘indistinguishable from the landscape of our own village’ – Ivy Cottage, where he had lived with his mother and Ninny, was indeed almost uncannily like Mr Jeremy Fisher’s ‘little damp house’.

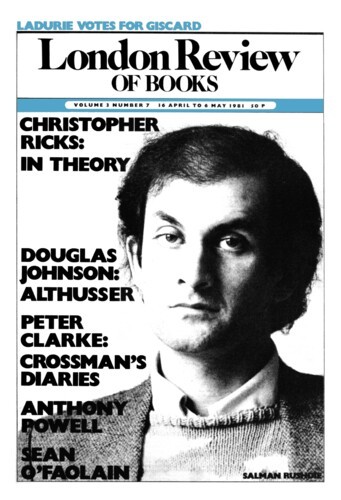

In appearance, Jocelyn Brooke was tall, pale, not bad looking, with an air of melancholy that would suddenly leave him when he laughed. Photographs give him a haggard air, a stare as if mesmerising or mesmerised (perhaps assumed for fun), that hardly does him justice. He often reminded me of George Orwell, not in feature so much as a kind of hesitancy of manner, thinking for a second or two of what had been said, but he had none of Orwell’s wish to set the world right, and his laughter was quite un-Orwellian.

I think that as a writer Brooke completely realised himself, in spite of dying comparatively young. He had said what he had to say in the form in which he wished to say it. No doubt his critical views would always have been of interest, but he had already marked out his own magical personal kingdom, one that makes him different (in a sense, what he himself felt) from any other writer.

Jocelyn Brooke quite often quotes A.E. Houseman, half-respectfully, half-deprecatingly, as if finding the shared rural images, shared homosexuality, both a shade too lush for his own taste, while all the same admiring the poetic mastery. Nevertheless, one feels a suitable epitaph might be provided by only the smallest adaptation of Houseman’s often quoted lines:

Far in a Kentish Brooke-land

That bred me long ago

The orchids bloom and whisper

By woods I used to know.

Send Letters To:

The Editor

London Review of Books,

28 Little Russell Street

London, WC1A 2HN

letters@lrb.co.uk

Please include name, address, and a telephone number.