In this, the last novel we shall have from Barbara Pym, it is Miss Grundy, a downtrodden elderly church-worker, who says that ‘a few green leaves can make such a difference.’ The phrase echoes a poem which the author loved, but found disturbing, George Herbert’s ‘Hope’.

I gave to Hope a watch of mine: but he

An anchor gave to me.

Then an old prayer-book I did present:

And he an optick sent.

With that I gave a viall full of tears:

But he a few green eares:

Ah Loyterer! I’le no more, no more I’le bring:

I did expect a ring.

The book, in her accustomed manner, is both elegiac and hopeful. It gives a sense of pity for lost opportunities, but at the same time a courageous opening to the future.

High comedy needs a settled world, ready to resent disturbance, and in her nine novels Barbara pym stuck serenely to the one she knew best: quiet suburbs, obscure office departments, villages where the neighbours could be observed through the curtains, and, above all, Anglican parishes. (Even as a child at school she had written stories about curates.) This meant that the necessary confrontations must take place at cold Sunday suppers, little gatherings, visits, funerals, and so on, which Barbara Pym, supremely observant in her own territory, was able to convert into a battleground. Here, even without intending it, a given character is either advancing or retreating: you have, for instance, an unfair advantage if your mother is dead, ‘just a silver-framed photograph’, over someone whose mother lives in Putney. And in the course of the struggle strange fragments of conversation float to the surface, lyrical moments dear to Barbara Pym.

‘An anthropophagist.’ declared Miss Doggett in an authoritative tone. ‘He does some kind of scientific work, I believe.’

‘I thought it meant a cannibal – someone who ate human flesh,’ said Jane in wonder.

‘Well, science has made such strides,’ said Miss Doggett doubtfully.

Or:

‘Well, he is a Roman Catholic priest, and it is not usual for them to marry, is it?’

‘No, of course they are forbidden to,’ Miss Foresight agreed.

‘Still, Miss Lydgate is much taller than he is,’ she added.

In such exchanges the victory is doubtful: indeed, Miss Doggett and Miss Foresight are, in their way, invincible.

As might be expected, however, of such a brilliant comic writer, the issues are not comic at all. Three kinds of conflict recur throughout Barbara Pym’s novels: growing old (on which she concentrated in the deeply touching Quartet in Autumn); hanging on to some kind of individuality, however crushed, however dim; and adjusting the vexatious distance between men and women. These, indeed, are novels without heroes. The best that can be put forward is the Vicar in Jane and Prudence, ‘beamy and beaky, kindly looks and spectacles’, and, as his wife accepts, more than somewhat childish. If men are less than angels, Barbara Pym’s men are rather less than men, not wanting much more than constant attention and comfort. Their theses must be typed, surplices washed, endless dinners cooked, remarks listened to ‘with an expression of strained interest’, and the forces of nature and society combine to ensure, even in the 1980s, that they get these things. Women see through them clearly enough, but are drawn towards them by their own need and by a compassion which is taken entirely for granted. Men are allowed, indeed conditioned, to deceive themselves to the end, and are loved as self-deceivers.

Women have their resource – the romantic imagination. This faculty, which Jane Austen (and James Joyce, for that matter) considered so destructive, is the secret ‘richness’ of Barbara Pym’s heroines. ‘Richness’ is a favourite word. It means plenty of human behaviour to observe, leading to a wildly sympathetic flight of fancy into the past and future. Of course, one must come down to earth, the tea must be made, reason takes over: but the happiness remains. Richness can defeat even loneliness. In The sweet dove died pampered Leonora, on a visit to Keats House, looks in astonishment at a faded middle-aged woman with a bag full of library books, ‘on top of which lay the brightly-coloured packet of a frozen dinner for one ... And now she caught a glimpse of her [the woman’s] face, plain but radiant, as she looked up from one of the glass cases that held the touching relics. There were tears on her cheeks.’

Barbara Pym nevertheless guards against sentimentality. She is the writer who points out ‘the desire to do good without much personal inconvenience that lurks in most of us’, the regrettable things said between friends and ‘the satisfaction which is to be got from saying precisely things of that kind’, the irritation we feel ‘when we have made up our minds to dislike people for no apparent reason and they perform a kind action’. But towards her characters she shows a creator’s charity. She understands them so well that the least she can do is to forgive them.

For A Few Green Leaves she has moved back from the London of her last two novels to the country. Here, too, she has always taken a straight look. Why is it always assumed that English women must ‘love’ the country, and be partial to dead birds and rabbits, and to cruel village gossip? Why are those who dig the garden and keep goats called ‘splendid’? But, at the same time, this is Oxford-shire, the ‘softly undulating landscape, mysterious woods and ancient stone buildings’ where Barbara Pym herself spent her last years.

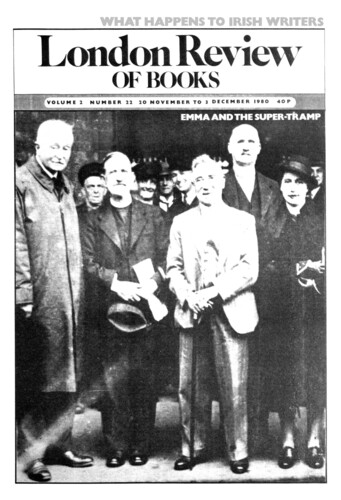

The heroine, Emma Howick, who does not mean to settle there permanently, undertakes some quiet research into her fellow creatures (rather like Dulcie in No Fond Return of Love). The original inhabitants of the village have withdrawn to a council estate on the outskirts, leaving the stone cottages to elderly ladies and professional people. Here she begins her field notes. Changes in village life are a gift to the ironist, but Barbara Pym has placed such changes – seen partly through Emma’s eyes and partly through her own – in relation to an unexpected point, the human need for healing. The almost empty church confronts the well-attended surgery (Tuesdays and Thursdays). ‘There was nothing in churchgoing to equal that triumphant moment when you came out of the surgery clutching the ritual scrap of paper.’ The lazy old senior partner is ‘beloved’, the junior partner’s wife schemes to move into the Rectory, far too large and chilly for the widowed Rev. Thomas Dagnall. Even a discarded tweed coat of the young doctor’s is handed separately to the Bring and Buy, ‘as if a touch could heal’. But when, in the closing pages, he is obliged to tell a woman patient that her days are numbered – for it’s no good trying to hide the truth from an intelligent person – ‘she had come back at him by asking if he believed in life after death. For a moment he had been stunned into silence, indignant at such a question.’ In this indignation we get a glimpse, no more than that, of a pattern which Barbara Pym chose to express only in terms of comedy.

The story proceeds from Low Sunday to New Year through delightful set-pices – a Hunger Lunch, a Flower Festival, blackberry-picking (but the hedges turn out to have been ‘done’ already). Tom and Emma must draw together, that’s clear enough. Both of them feel the unwanted freedom of loneliness. Daphne, Tom’s tough-looking elder sister, is yet another romantic:

‘One goes on living in the hope of seeing another spring,’ Daphne said with a rush of emotion. ‘And isn’t that a patch of violets?’ She pointed to a twist of purple on the ground, no rare spring flower or even the humblest violet, but the discarded wrapping of a chocolate bar, as Tom was quick to point out.

‘Oh, but there’ll soon be bluebells in these woods – another reason for surviving the winter,’ she went on ... Young Dr Shrubsole moved away from her, hoping she had not noticed his withdrawal.

Who can say which of them, in the satirist’s sense, is right? In the same way, the villagers intimidate the gentry, and the old are intimidated by the young, who preserve them and educate them in healthy living and make them carry saccharine ‘in a little decorated container given by one of the grandchildren’ – but in both cases Barbara Pym gently divides her sympathy. We have to keep alert, because she will never say exactly what we expect. The ‘few green leaves’ of the title come from a remark of Miss Grundy’s, made to Tom, who reflects how often these elderly women give him, quite unconsciously, ideas for a sermon: ‘He made up his mind not to use them.’

Through all Barbara Pym’s work there is a consistency of texture, as well as of background. She has described the texture herself as ‘pain, amusement, surprise, resignation’. This makes it possible for characters to stray out of their own novel into another: in A Few Green Leaves, for example, we hear about the funeral of Miss Clovis, from Less Than Angels. The valedictory note cannot be missed. But, once again, the ending is an encounter with hope, as Emma determines to stay in the village, ‘and even to embark on a love affair which need not necessarily be an unhappy one’.

Send Letters To:

The Editor

London Review of Books,

28 Little Russell Street

London, WC1A 2HN

letters@lrb.co.uk

Please include name, address, and a telephone number.