‘Davies? Oh, he was a sort of natural, wasn’t he – like Clare?’ James Reeves’s Introduction to his Penguin anthology of Georgian poetry puts this absentminded question into the mouth of an unidentified intellectual of recent times. It refers to the author of the present book, who is also the author of the once-famous Autobiography of a Super-Tramp and of some six hundred poems. Young Emma is a sequel of sorts to the Autobiography, but it is a startlingly different performance. It will restore Davies, for a season, to the prominence from which he has fallen since his death in 1940, though there are others besides Reeves who have remembered him, and Old Mortality Larkin has removed the lichen from his grave with an ample display in the Oxford Book of 20th-century Verse. This posthumous fame, however, may prove to be of a kind Davies would not have welcomed. He was a strange person, and one whose interest in publicity blew hot and cold. This book is indeed the work of a natural, if by that we may mean someone who took to reading and writing as a bird to the wing, and who was a bit of a simpleton. In the supportive Introduction which he wrote in 1907 for The Autobiography of a Super-Tramp George Bernard Shaw calls him an ‘innocent’. Davies – the wisest fool ever to escape from a dosshouse? The second of the autobiographies will cause some people to think of him as a holy fool rather than a wise one, while others will be quick to dispense with both adjectives.

Raised in Monmouthshire, he spent a footloose youth as a hobo and beggar, and actually lost a foot hopping freights in America. But he also worked during this time, as a casual labourer. The work was hard, and could be hard to find: these were the golden days of the past, when there was no work problem – in the sense we may assign to Ronald Reagan’s claim that there was then no race problem. In Davies’s America there was a race problem, and the Autobiography describes a lynching, treating it as a pretty satisfactory affair: the description, which could well at one time have helped to spread distaste for racism, is itself racist. The mob are stern dispensers of justice: ‘no cowardly hand’ strikes the Negro when he is dragged from the jail. He is strung up and a hundred bullets are fired at him. Shortly before this, Davies has been deploring the 39 cowardly cuts inflicted on a man by six Negroes, and shortly afterwards he is himself mugged by blacks who have not bothered to check, first, that he is worth robbing. He thinks this a crime that white men rarely stoop to: they check first, and ‘do not resort to violence, except it be their victim’s wish’. Blacks are ‘born thieves’. He does not say that in this they are like some of his own best friends among the tramps.

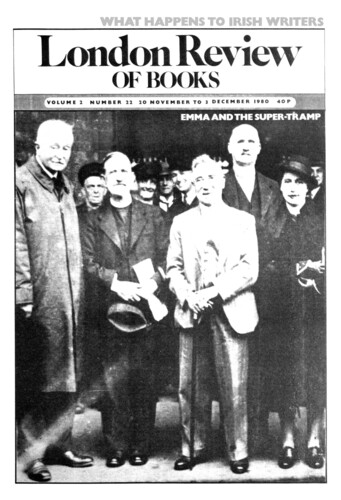

According to this account, the tramps he lived with were a ceremonious and grammatical body of men; they were not, pace Shaw, without honour; there were no wild men like the down-and-out depicted on this page by Don McCullin. The new memoir suggests that the old one was out to uphold a decorum: it is the work, for example, of a celibate who never mentions the subject of sex. The new one, by contrast, gives glimpses of dereliction which can bring to mind the world explored by Beckett: Davies himself is at moments Malloy-like. The earlier text is more intensively worked; it is stocked with very good yarns in which this strange person takes a romantic interest in ‘strange’ things. But it is the less truthful book of the two.

Conscious of himself as a creative genius, Davies was cultivated by London bookmen and clubmen as a natural in another sense again: as an untutored talent from the depths of the common people. Such phoenixes are, of course, a traditional and ancient thing, and the line taken in Shaw’s Introduction belongs to a long history of kindly condescensions. Here and there, however, Shaw gets Davies remarkably wrong, and exaggerates the extent of his deliverance from convention. This wanderer was not very licentious; this refugee from convention was following the convention of the rover, and of the rover’s return; when he wasn’t having adventures, sitting round camp-fires and touching householders for food and money, he was earning his living, and mustering the ambition to try for literature as a career. The author of the present book appears to look up with reverence from a low point in the social hierarchy: ‘His offer to marry her was made indifferently,’ he writes, ‘with all the splendid generosity of a young officer.’

As a poet, he was so far from untutored as to be excessively bookish. Shaw enthuses that his poetry is not modern, is unmarked by an acquaintance with any verse later than that of Cowper and Crabbe. This is a silly romantic aspersion on Romanticism. From a man who might never have read any, we hear that it is right for poetry to pay no attention to previous poetry. Shaw claims that Davies pays no attention to Keats: but there are poems by him which are comical Keats pastiche, like ‘Autumn’, which accompanies the Autobiography, and ‘A Dream’, whose title probably alludes to the poem which it imitates – ‘La Belle Dame Sans Merci’. Here Davies encounters a female in the woods who lures him with a supernatural gymnastics to her cave or elfin grot:

She laughed and danced around;

Back-bending, with her breasts straight up,

Her hair it touched the ground.

In the cave she administers a good biting

And what is this, how strange, how sweet!

Her teeth are made to bite

The man she gives her passion to,

And not to boast their white.

O night of Joy! O morning’s grief!

For when, with passion done,

Rocked on her breast I fell asleep,

I woke, and lay alone.

This may seem naive, but, as poetry, it is neither innocent nor natural. Davies was not long in liking Keats. Wordsworth, with his fondness for statistics, came later, and Davies wrote:

I judged it was seven pounds in weight,

And little more than one foot long.

A tremendous smoker of his pipe, Davies was blushingly mild and shy in his daily life, or so the new book makes out. But there was a violence in him which bared its teeth in dreams and which contributes to his successful poems. Such poems by Davies do exist, like the one in which a parrot seems to speak his sailor’s foul mind for him, and Larkin did well to include in his anthology:

I turned my head and saw the wind,

Not far from where I stood,

Dragging the corn by her golden hair,

Into a dark and lonely wood.

Davies began Young Emma in his 50th year. Not very long before, just after the Great War, the time had come for the Super-Tramp to settle down. He was living frugally and in humble circumstances in the West End of London. Settling down meant marrying and moving to the blissful country. It meant walking the streets of London and staring into the faces of the many ladies who were doing the same, anxious to meet a man, preferably one in a handsome overcoat, and prepared to put up with a civilian now that the military had melted away. It meant a great deal of accosting: a favourite word of his, for an activity which, in one form or another, dominates each of these books. We all know men who go in for this, and there is a joke which says that they get plenty of refusals. But the joke also says that they make plenty of friends, and so it proved with Davies.

Britain has now become an unfortunate country, and among its misfortunes are the lies we have had to listen to about the order and decorum of its past – puritanical lies, especially, about a former absence of self-indulgent sexual behaviour. Both books report a high incidence of drunkenness and casual violence among the poor, with Britain worse than America, and those who were shocked by the Swinging London of the 1960s and 70s might benefit from reading about the state of affairs there around 1919 – as seen through the country-cousin eyes of an eccentric simpleton who had nevertheless travelled the world and is no unworthy witness to the droves of tired amateur whores who used to rest out the daylight hours in Hyde Park. Your well-dressed man was very popular in 1919:

Many a strange woman who passed him by would give him the invitation; and he could raise his hat and speak without fear of accosting a respectable woman. On this occasion I was dressed smartly in a light overcoat, which was almost new, and it was this that probably made a number of women smile and come to a very slow walk, to enable me to make the next advance. But here I must make another confession which may appear strange indeed. It is this – I am a very shy man. For instance, if one of these women did not actually come to a dead halt and speak to me first, it is not at all likely that I would have turned back and followed her, however much I might have been impressed by her beauty, and however cordial might have been her greeting. Time after time have I gone out looking for a woman, and time after time have I returned home alone, because I have not had the courage to lake advantage of a woman’s encouragement. This is the reason why I have never made a mistake in accosting a respectable married woman, in spite of my dealings with scores of other strange women, through a number of years as a single man. As far as I can remember, every woman that I have had dealings with has come up to me boldly and told me why, before I could express am thought of my own. But what I have said before, about having an honest-looking face, has stood me well in cases of this kind; for women have, more than once, given me far more encouragement than I could have expected from them.

This shyness is sometimes so painful that I have to take two or three strong drinks before I can look at a woman, in spite of having gone out on purpose to meet one. I am very pleased to be able to make this confession; otherwise in the following adventure I would appear like the strong, crafty, designing man of middle age on the look-out for a young and innocent girl.

Once bitten, twice shy ... Davies may be said to have learned to suspect women but not to avoid them. Women, he felt, were unsafe with drink and money: accosting cost money, just as settling down meant settling up, and the master sex counted out cash for the groceries in the knowledge that the lady might bolt with it. A drinker himself, he believed that ‘a woman who drank was not to be trusted.’ A loner, he had no trouble in taking strange women back to his flat and ‘cohabiting’ with them. Encounters and friendships of this kind open the present account: some of the women swore like troopers, stole like tramps or blacks, and were menacing and disturbed in jealousy or drink. Bella, for instance, drank and was merciless with his possessions. She fancied a clock of his: ‘When I came back it would be certain that two faces would be missing – for there would be no Bella and no clock.’ She took the clock, and it was missed by French Louise, whose suspicion that she had a rival was confirmed by the discovery of a pair of hairpins in his flat. ‘You traitor with the double face,’ she stormed. This play on the two sorts of double face may register with some as a stylistic stroke on the author’s part. Davies’s Introduction states: ‘Although the work may be praised for its style and language, I would not like anyone to think or say that the matter itself is foul.’ The matter is not foul: but the style is simple enough throughout to convince the reader that this play was inadvertent.

After these dramas with Bella and Louise there occurs the ‘following adventure’ to which he refers in his piece about accosting. He is smiled at by a woman in the Edgware Road, and his first words to her are an invitation to go home with him. They then cohabit, or sleep together. Emma is a country girl, and more unequivocally simple than Davies – able to believe that no one could ever be so unchivalrous as to require women to pay taxes. It seems that they will manage to love one another, but their love does not run smooth.

He thinks she has infected him with a venereal disease, and he is soon bedridden with a related rheumatic ailment in his foot. The fact that he has only the one foot is not mentioned in the book (you may have noticed that it was inadvertently mentioned in a poem): the account is presented as that of a celebrated writer who wishes to remain anonymous, a ‘shy and quiet man’, as he calls himself, ‘who had always tried to shun the public eye’. It is really strange that such a fellow should initially have intended to publish the account, with all that it contains of the normally or Edwardianly undisclosable: it is unlikely that he was responding to the advanced thought that the times had changed, and that convention and expression should change with them, but the war could well have enlarged his notions of what was fit to print.

Meanwhile Emma, too, falls ill, and is rushed to hospital, where she gives premature birth to that splendid young officer’s child: the child dies. The couple weather these tumults to the best of their ability, and depart for the idyllic country retreat – Nailsworth in Gloucestershire, I gather – which they richly deserve. There is an ironic outcome, in that Emma is discovered not to have transmitted the disease, after all. A dangerous drinking woman of the upper class may have been responsible. Was Davies cured by the time of his departure for the country? The clinical aspects of the story are rather obscurely rendered.

Davies had wanted to retire from ‘society’: he had never really warmed to it, and in any case, ‘I cannot hold my water long enough for a prolonged conversation.’ Emma suited his needs very well, and was his wife for ever after. He needed to have a kind helpmeet, housewife and clinging vine, and to be a kind lord. This woman from the lottery of the London streets afforded him the marriage of his dreams, which was completed by a dog, a cat and a garden. She is domestic, not literary; she does not read his stuff; she is like Madame Mallarmé. He seems to be celebrating her in the lines:

If this young Chit had had more sense

Would she have married me?

That she gave me the preference,

Proved what a fool was she:

Then let me die if I complain

That Beauty has too small a brain.

Author’s wives have often been treated in this invidious fashion, in the course of the last hundred and fifty years. Davies took his country walks alone, so as to have his thoughts and ideas, and these charming lines celebrate the return to his garden:

Where bumble-bees, for hours and hours,

Sit on their soft, fat, velvet bums,

To wriggle out of hollow flowers.

It all makes a much better story than it does a book. But this is not the whole of that story. Davies himself does not appear to tell the whole of it. His simplicity and self-centredness prevent this, and this book is like the type of lyric poem in which the personality of the poet is obtruded. Her ‘Bunnykins’ seldom allows Emma to speak her mind, and at times it is as if she does not have one. And at most times she is an enigma. This has artistic advantages, since we have to think of Davies as a man on his own who does not know what day of the week it is, and he does explain that Emma’s dependence on an older man may have derived from a similar relationship between her parents. Not that we have to think of her as peculiar: we are brought to recognise that any poor woman needed protection in the good old days of 1919. Quite apart from these considerations, there is an important part of the story which Davies was in any case in no position to tell. This concerns the fate of the manuscript, which is discussed by C.V. Wedgwood in a Foreword, and it also concerns the involvement in its fate of his wife.

He winged his way through this book not long after the events it records, intending, as I say, to publish anonymously. The publisher Jonathan Cape was against the project, Davies lost confidence in it, and there was a vague understanding that the copies of the manuscript would be destroyed. A copy survived at Cape’s, and at various times publication was mooted. The snag was the widow, who survived her husband for many years and who would be injured by the book. It would have been a delicate task to draw her into conference on the decision, though she seems to have been to some extent aware of the book; and the reader is left to assume that she was considered but not consulted. But it is perhaps of interest that we are nowhere told that she was not told: it is as if it was natural that these latterday transactions should have gone on over the head of the author’s wife. It is no less of interest that Davies was once willing (though twice shy) to tell the world, concerning his marriage, what was never to be communicated in full to his wife, for all that she may have gained a sense of all or nearly all the relevant facts. Now Emma is dead and at last the story is out, like murder, and the poor old souls, in their agony and ignorance, are being serialised in one of the two high-minded Sunday papers which carry so many of the scandalous actions of the writers of the recent past – so many of the sodomies, adulteries and sexually-transmitted diseases of the artists who belonged to the golden age that ended with our current misfortunes.

Shaw advised against publication in a letter of 1924 which rounds off the book. He calls the manuscript ‘an amazing document, just like the old one’. But in his Preface of 1907 he had called the Autobiography ‘unexciting in matter and unvarnished in manner’. So what had been amazing about it? Shaw’s Preface struggled to say what. It appears to have been that a poor man, a man from beyond the pale of respectability, had produced a book which defied convention. In the letter of 1924 Shaw supplies reasons for advising against the publication of Davies’s new and hugely disconcerting confessions: it would damage the author’s wife, and damage Davies by indicating that the literary world, and the friends of his middle age, are as ‘completely alien to him as they were when he was a tramp’. The second point is as sound as the first: Davies may have cared more about the calves and lambs he speaks of in his poems than he did about human beings, Emma excepted, and he may have had more time for books than bookmen. Shaw says that he is all in favour of publishing all ‘genuine documents’: an unconventional position, possibly, by the standards of the time. But he is conventional enough to add that he would be sorry to see suppressed ‘even Joyce’s Ulysses’. Those were the days.

Send Letters To:

The Editor

London Review of Books,

28 Little Russell Street

London, WC1A 2HN

letters@lrb.co.uk

Please include name, address, and a telephone number.