The first issue of the London Review of Books appeared on 27 September last year, and the present issue is the 14th we have produced. The journal was started when some newspapers were in abeyance, and others had taken to cutting back on the space allowed for the discussion of books. Publishing houses were rumoured to be in financial difficulty – such as Penguin – and Collins were presently said to have become ‘over-heated’ in Australia. Publishers were felt to be peculiarly exposed to the fortunes of the economy, and the country, for all its oil rigs, was felt to be keeling over. It is still felt to be keeling. But the absent newspapers have resumed. Publishing houses have righted themselves. And it is also the case that the whole British rig has yet to descend into the North Sea.

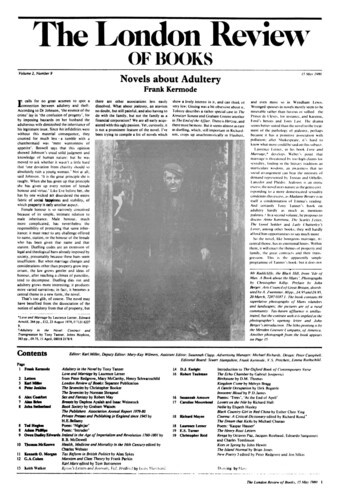

So far, the London Review of Books, while editorially separate, has appeared within the New York Review of Books. This was always seen as a temporary arrangement, and it is soon to cease. With effect from the issue which goes on sale on 22 May – two issues from now, that is to say – we shall be coming out on our own, twice a month. The New York Review will be represented on the board of the company which has been formed for this purpose. But from now on the London Review will not only be edited in Britain: it will be British-controlled. Subscribers in Britain and Europe will continue to receive both papers, and when subscriptions come up for renewal, they will be invited to re-subscribe to one or the other, or to both.

I am not trying to make us sound like ICI or Courtaulds. We are, and shall remain, a small paper. Perhaps it needn’t be explained that we are not so much interested in expansion and profit as in being a place where good writers can be published, and new books examined and evoked. We started at short notice – a month’s notice, to be exact – and with a part-time editorial staff of four we have had to improvise our way through the difficulties which any small paper is certain to meet. The response we have had from writers has been very good, though we were not long in discovering where we could least expect to gain attention: of those who have refused to write, or who have promised and failed to deliver, almost all have been MPs. For our first six months, the circulation has stood at around the 15,000 mark.

Many of our readers are outside the university fold, and we are pleased about that. We will continue to review academic books, but are keen to reach that wider community of informed and interested readers which used to be among this country’s claims to fame and which can’t have melted into the sea. We mean to extend our subject-matter when the paper separates: there will be more in the way of argument and reporting, more pictures, and some fiction.

The university fold is sometimes said to be devoted to the business of structuralism, semiology, post-structuralism, deconstruction. Whether or not this is true, it has been clear, over the past six months, that the subject is second only to Marxism as a source of new titles in the higher publishing. There are publishers who are now pouring out, at a quite astonishing rate, titles which contain the word ‘language’ or the word ‘structure’, with the word ‘revolution’ frequently subjoined. Britain makes no films to speak of any more: but it maintains, not only a national Film Institute, but also, in magazines, manuals and manifestos, a busy structuralist critique of the medium. Structuralism is the philosophy of those in the universities and thereabouts who are not philosophers; it is the philosophy of English departments and teacher-training institutes throughout the English-speaking world. The propagation and diffusion of these ideas would be a matter worth serious study, but it is not one that will figure, for a long time if ever, among the flow of new titles.

It follows that any journal that seeks to address an academic readership might take care to address itself to these themes. We stated at the outset, rather ingenuously, that we would not be sympathetic to them, on the whole. But we have not avoided them, and the next issue will carry two substantial discussions – from opposing standpoints, those of the Australian S.L. Goldberg and the Englishman Roger Poole – of structuralism’s current mode: deconstruction.

At the same time, over these same six months, a reaction against this tendency has surfaced in books and articles both here and in America. Structuralism has become visible in journals of general circulation – and has been represented there as an object of horror. It has been sweepingly asserted that it is sinister nonsense. This clean sweep has the disadvantage of obscuring the fact that some nonsense has a way of invigorating, and of being reconstituted by, literary talent, and that structuralism isn’t all nonsense anyway. Even deconstructionists would probably be ready to admit that there have been hardly any innovating or important contributions to the subject by a British writer, and that British and American enthusiasts alike have profoundly depended on French initiatives: but it is not impossible, it is even likely, that such contributions may come. Many opponents of deconstruction would admit that Roland Barthes, whose death occurred the other day, was highly talented, and they could well have been moved by the praise accorded him in a Times obituary tribute (corrective of the main obituary, which was held to be insufficiently enthusiastic): ‘Barthes overrode the distinction that is usually made between the creators of literature and its critics: he thought both could be classed as writers. He was most certainly a writer himself ...’

The attacks that have been launched have served to bring out two aspects of deconstruction which must necessarily concern any journal which seeks to address the general reader (who may not be very different from Barthes’s non-specialist reader-as-writer). First, a contradiction is apparent between the stress on language as mediation or communication and the stress on language as itself authorial, as responsible for the literary text to a degree that diminishes both the author of the text and the capacity of the text to refer, practically, purposively, instructively, to the world beyond language. Deconstruction is in this sense a withdrawal, a rejection, and a confession of defeat. As such, it is a suitable approach for an Englishman or American of the present time. The word itself signals rejection. It is a strange, hard word, a punk word, a word that keeps people out with its scowling newness and difficulty, a word for initiates or specialists. The structuralist vocabulary bristles with such words, and with words which refuse to be what language intends to be – understood, and enjoyed.

But if deconstruction conveys that there is nothing to be done, it also conveys that there is plenty to be said. The second of these two aspects relates to the willingness of the defeated to write books. Deconstruction resembles other enthusiasms of the present time in enabling established topics, and famous authors, to be dealt with all over again from the new point of view. The new point of view can help to swell the academic curriculum vitae, with its anxious list of publications. The new point of view can be appointed to posts. So there on the shelf, awaiting their reviewer, sit A Structuralist Reading of Charlotte Brontë, Deconstruction and D.H. Lawrence, and the rest of them. A writer in the American magazine Commentary, Michael Vannoy Adams, gives this account of some of the arguments in Gerald Graff’s anti-deconstructionist philippic, Literature Against Itself:

The deconstructionists render literature invalid or ineffectual by default; they deprive literature of the relevance it ought, by all rights, to have, and they reduce criticism from a serious and influential discipline to a frivolous and inconsequential – and quite expendable exercise. Why, then, have they captured the English departments of so many universities and become so dominant on the academic landscape? Graff offers an economic explanation. He says that sheer quantity of output, not quality, is the way to tenure and promotion in the university today. For English departments to insist on a real standard of excellence in literary criticism ‘would be comparable to the American economy’s returning to the gold standard: the effect would be the immediate collapse of the system’ – the academic system depending as it does on mass production (publish-or-perish). Hence the urgency to produce new (not stricter) methods of literary criticism, which produce different (not truer) interpretations, which produce more (not better) publications. According to Graff, the deconstruction of texts is make-work, a mere game that critics now play when the ‘explication of many authors and works seems to have reached the point of saturation’.

It seems, then, that the confession of defeat can lead to publication and to promotion. There is nothing uniquely sinister about this: structuralism is not the only set of ideas which has been put to work for professional advancement. But it would be wrong to omit their professional usefulness from any assessment of the factors which have governed the transmission and diffusion of these ideas. Structuralism unites aggression and retreat. It both desires and disdains to make converts. It is a thriving discourse which expects to bewilder; its popularity is that of the designedly unpopular. So, while it is perfectly true that its ideas have travelled further and wider than can generally have been thought likely in the days when they were first identified, it is also true that the general reader does not know about it – that, at the last count, so to speak, only two MPs in the House of Commons had ever heard the name, and both of them were Bryan Magee. This doesn’t prove the ideas wrong, or right. But it does indicate that even a small paper has to have more than one readership.

Send Letters To:

The Editor

London Review of Books,

28 Little Russell Street

London, WC1A 2HN

letters@lrb.co.uk

Please include name, address, and a telephone number.