A Deer in Glanmore

for B.C.

About a mile above

and beyond our place,

in a house with a leaking roof

and cracked dormer windows

Brigid came to live

with her mother and sisters.

For months after that

she slept in a crowded bed

under the branch-whipped slates,

bewildered night after night

by starts of womanhood,

and a dream troubled her head

of a ship’s passenger lounge

where empty bottles rolled

at every slow plunge

and lift, a weeping child

kept weeping, and a strange

flowing black taxi pulled

into a bombed station.

She would waken to the smell

of baby-clothes and children

who snuggled tight, and the small

dormer with no curtain

beginning to go pale.

Windfalls lay at my feet

those days, clandestine winds

stirred in our lyric wood:

restive, quick and silent

the deer of poetry stood

in pools of lucent sound

ready to scare,

as morning and afternoon

Brigid and her sisters

came jangling along, down

the steep hill for water,

and laboured up again.

Familiars! A trail

of spillings in the dust,

unsteady white enamel

buckets looming. Their ghosts,

like their names called from the hill

to hurry, hurry past,

a stone’s-throw of syllables.

I knew the story then.

With their margarine boxes,

pram wheels and biscuit tins,

they had missed their last bus

on that first night in Dublin

and walked miles of suburbs

all through the small hours.

How it sweetens and disturbs

as they make their homesick tour,

a moonlight flit, street-arabs,

the mother and her daughters

walking south through the land

past neon garages,

night-lights haloed on blinds,

padlocked churchyards, bridges

sturdy over a kind

mutter of streams, then trees

start filling in the sky

and the estates thin out,

lamps are spaced more widely

until a cold moonlight

shows Wicklow’s mountainy

black skyline, and they sit.

Brigid, now I am Davin

walking a dark road,

you are the young woman

who crept into his head

out of a roadside cabin

still following, and followed.

Near Anahorish: a Visitation

For Louis Simpson

I

I stood between them,

the one with his scanning intelligence

and fencer’s containment,

his speech like a bowstring,

and another, unshorn and bewildered

in the tubs of his wellingtons,

smiling at me for help,

faced with this stranger I’d brought him.

II

Then the cunning voice of poetry

came out of the field across the road

saying, ‘Be adept and be dialect,

tell of this wind coming past the zinc hut,

call me sweetbriar after the rain

or snowberries cooled in the fog.

But love the cut of this travelled one

and call me also the cornfield of Boaz.

Go beyond what’s reliable

in all that keeps pleading and pleading,

these eyes and puddles and stones,

and recollect how bold you were

when I first visited you

with departures you cannot go back on.’

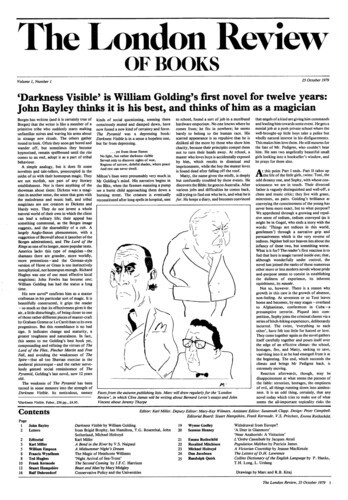

Send Letters To:

The Editor

London Review of Books,

28 Little Russell Street

London, WC1A 2HN

letters@lrb.co.uk

Please include name, address, and a telephone number.