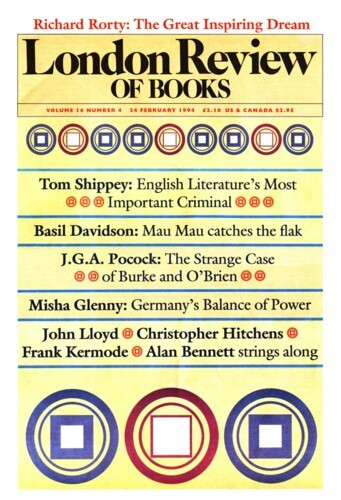

The Best

Tom Shippey, 22 February 1996

Pre-Conquest England – England, that is, between the departure of the Romans and the arrival of the Normans – notoriously has no presence even in the educated popular mind. Its history is unknown except to specialists, not part of the school curriculum, regarded as part of the Dark Ages. Since everything began in 1066, the Hammer of the Scots can occupy all history books as ‘Edward the First’, his namesakes the Confessor and the Elder literally felt not to count – even though the latter’s mark may still be visible on the shire system of Central England. As for the Egberts and Oswigs and Cerdics, the incompetences of modern spelling have left them all unpronounceable, vaguely ludicrous.’